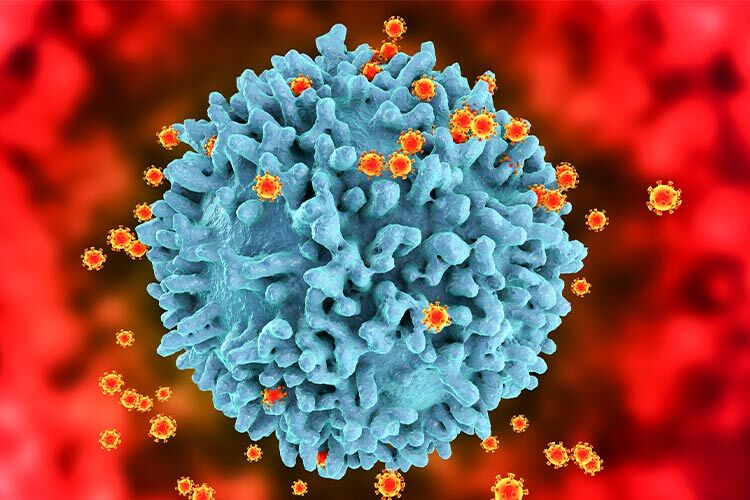

The injectable HIV medication lenacapavir has been selected as the 2024 Breakthrough of the Year by Science magazine. Following remarkable results from two large-scale clinical trials that demonstrated a complete reduction in new HIV infections, this groundbreaking treatment offers a glimmer of hope for reducing the virus’s incidence worldwide.

The publication emphasized that HIV continues to infect over a million people annually, while a vaccine remains out of reach. “But this year the world got a glimpse of what might be the next best thing: an injectable drug that protects people for 6 months with each shot,” Science noted.

The Impact of Lenacapavir in Two Clinical Trials

Although injectable lenacapavir has been available for two years as a treatment for individuals who do not respond to other medications, it now stands poised to become the most effective form of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), says Science.

In June, lenacapavir revolutionized PrEP by reporting zero infections in a blinded study of more than 5,000 cisgender women and adolescent girls in South Africa and Uganda who received the injections.

By September, a second PrEP trial using lenacapavir recorded only two infections among over 2,000 cisgender men, transgender men and women, and non-binary individuals who have sex with men across South America, Asia, Africa, and the United States.

“You don’t see data like this every day,” said Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, a nonprofit organization originally established as the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition and now increasingly focused on advancing PrEP solutions.

Unveiling the HIV Capsid Protein

Another reason lenacapavir earned the title of Breakthrough of the Year is its foundation on a novel understanding of the HIV capsid protein’s structure and function. The drug targets and inhibits this protein to achieve its effects.

“Many other viruses have their own capsid proteins, which form a shell around their genetic material, making the success of this drug an exciting step toward developing similar inhibitors for other viral diseases,” the article explained.

Unlike traditional HIV medications that disrupt viral enzymes by binding to their active sites, lenacapavir interacts with the capsid proteins forming a protective cone around the viral RNA. Initially, researchers considered the capsid an “unviable” target for drugs. However, recent discoveries revealed the cone to be a stable yet flexible structure, enabling Gilead scientists to develop lenacapavir.

The main challenge was the drug’s low solubility, which hindered its absorption. Transforming it into an injectable form turned this limitation into its greatest advantage, granting it an exceptionally long half-life in the body.

Approved in the United States in 2012, oral PrEP pills offer strong protection against HIV but have faced barriers in lower-income countries due to limited access and societal stigma.

A “Turning Point” in HIV Prevention

According to Science, lenacapavir could be a “turning point” in getting closer to achieve the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) goal of reducing new infections to below 370,000 by next year and fewer than 200,000 by 2030.

The drug’s potential also lies in scaling production and ensuring accessibility, said Linda-Gail Bekker, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Cape Town who led one of the efficacy trials for the Gilead Sciences-developed drug.

The pharmaceutical company plans to produce a low-cost generic version for 120 developing countries, though others, such as Brazil, will not yet benefit from this discount.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx