No, engineering isn’t “square.” For these female Tec graduates, it is one of the most creative and innovative professions. They have managed to position themselves at the highest level in their fields and are breaking the glass ceiling and gender stereotypes.

TecScience talked to these Mexican engineers, and they told us what they are passionate about, what obstacles they encountered along the way, and what advice they give to other women who want to succeed.

Dalia Carolina Ramos, the engineer who became a leader by believing in herself

Mechatronics engineer, Head of Build and Test for the Alpine Formula 1 team

Dalia Ramos was born in Mexico City, is 34 years old, and has always been a leader. Before heading the Alpine Formula 1 team’s Build and Test department, she was team leader of a major manufacturing project at Rolls Royce.

She is used to leading teams of men (often older than herself). Dalia says she achieved this with determination and with an attitude that combines confidence and humility and recognizing and learning from the work of others.

The department she heads at Alpine (formerly Renault) is responsible for the assembly, testing, and homologation of Formula 1 cars driven by race car drivers Fernando Alonso and Esteban Ocon.

She says that she has been very good at mathematics and physics since childhood and always received scholarships. When she chose her professional studies, she opted for Mechatronics Engineering at Tec de Monterrey’s School of Engineering and Sciences because it was a new and very innovative field.

“At the time, it was the challenge of challenges because I had to maintain scholarship for excellent grades at the best university in Mexico in one of the most demanding fields. That forged my character. It gave me a lot of security. It made me realize that no matter how complicated the challenge, the car, the turbine… I can do it.”

What makes you passionate about engineering?

The idea of doing innovative things, of inventing and developing something new. My motivation for studying engineering was to be able to help society, to make things possible that people thought were impossible. Your brain is always working and innovating in engineering.

What do you like most about your current job?

The Formula 1 car brings together many disciplines, and the fact that we have to improve it every week, looking for solutions, makes it a never-ending problem. I also really enjoy working with people, having a team, taking care of the people in the team and developing them. It is something very technical that, at the same time, involves the human factor a lot.

Do you think that being a woman brings something extra to your work as an engineer?

I believe that women approach problems in a different way, and that complements and balances a team. Men are much more practical. We think of several problems at once. As a woman, I think I can be more empathetic.

Did you have any role models that pushed you to go into engineering?

Not really. My grandparents are from the countryside. My father is a merchant, and my mother didn’t finish college. My sister and I were the first engineers in the family. However, from an early age, my parents made me see that I was smart and special, that I could do whatever I wanted and go far if I worked hard.

What’s been the most challenging project you’ve worked on?

I was in a leadership program at Rolls Royce and headed a project to set up a pilot plant, which meant assembling robots, getting them started, and connecting them to all the systems in the factory.

It was technically complicated, but the person I was in charge of didn’t respect me, and he was very difficult to handle, so I had to confront him, stop him in his tracks, and ask him what his problem was and why he thought we couldn’t work together.

Obviously, it wasn’t easy, but the story has a happy ending because he became my best ally. Since then, I’ve gotten used to confronting people, without being afraid.

What qualities do you think a good engineer should have?

One thing I’ve learned is that maybe you don’t have all the answers, but you have to know how to ask the right questions to understand a problem. You also need to be confident in the technical decisions you make. Sometimes you don’t have all the elements or all the numbers, but you have to have confidence in the logic of your decision.

What’s the worst thing about being a female engineer?

We have to fight a little more for respect and credibility. There are many stereotypes and paradigms about the role that women should play in society, and we have to break them, not only on the outside, but also on the inside. I say this because I have also struggled with myself. The good thing is that I believe we’re the generation of change.

What advice would you give to future female engineers?

I’d tell them to never think that there are male and female professions. There’s no such thing! I don’t believe in the idea that women are better than men. I think we complement each other, and we should make the most of that combination. I think that women in engineering right now can find many support networks.

Jenifer Avellaneda, the nuclear engineer looking to combat climate change

Nuclear engineer, Westinghouse Electric Company

Interestingly, her passion for the nuclear area came about when she read Dan Brown’s novel Angels and Demons. At 12 years old, she asked herself many questions about the world around her. While investigating, she arrived at atoms and atomic matter.

So, she decided to study something that would bring her closer to this industry. “You say ‘nuclear’ and people automatically associate it with bombs, but there’s a lot more to it than that. For example, I’m very concerned about climate change, and it’s very clear to me that we can generate green electricity safely and in large quantities with nuclear energy.”

Jenifer, who was born in Mexico City in 1995, currently works in assessing risk probability, which means determining how likely it is that any type of mishap or catastrophic event could happen in a nuclear plant and what actions should be taken to mitigate it.

What makes you passionate about engineering?

Being able to investigate, experiment, and develop information about the origins and processes that constitute daily life. Basically, being able to answer the why, how, when, and where of any process.

What do you like most about your current job?

That I have the resources and the materials to be able to rigorously defend why we should say yes to nuclear energy, why it’s safe, why it’s green, and why it should be considered renewable energy. It’s also a continuous learning process. I’ve been in my position for three years, and it still feels new because there’s a huge flow of information. I love that.

Do you think that being a woman brings something extra to your work as an engineer?

If you had asked me this question two years ago, I would have said no, that men and women are the same, but I have realized that this isn’t exactly the case. Their thinking is more linear and logical. Mine is more intuitive, more holistic, and a little more creative. So, I think we make an excellent combination. There are four men and me in my team, and they’re all over 50. In the beginning, I was quiet, observing, learning… but they gave me the confidence to make my thoughts and opinions known, and I realize that I complement them.

Did you have any role models that pushed you to go into engineering?

In the most recent part of my career yes, but not in the beginning. That’s precisely what pushed me to go into this career. I asked myself: Where are the women in these fields that interest me? I created my own role model and have worked to become that person that 12-year-old Jenifer dreamed about.

What’s been the most challenging project you’ve faced?

I’ve had several at work that are difficult to explain, but there’s a personal project that’s been very challenging.

It began when armed conflict broke out in Ukraine. When the Russians took over the Zaporiyia nuclear power plant, the largest in Europe, people began to speculate that the world was going to explode, that another Chernobyl would occur.

I realized that there’s a lot of misinformation, and I thought it was time to start a nuclear communication and outreach project.

I opened my Twitter and Instagram accounts (@NuclearHazelnut), and since then I’ve shared news on these platforms of what I know and what I’ve researched about this form of energy. Of course, I’ve met people who question me, who tell me that I don’t know anything, who ask how I can say such things, but that’s precisely what my project about, defending what I believe in and generating informed discussion about nuclear energy.

What qualities do you think a good engineer should have?

They must have an interest in constantly learning, but also an interest in teaching. not only to know things yourself, but to convey that knowledge.

What’s the worst thing about being a female engineer?

In many areas, men are in the majority and, if you’re young, they probably have more experience and look down on you. They think you don’t know; you have a lot to learn; and you’re there because of some help.

That’s bad, but at the same time, it’s been the best thing, because, at least in my case, I’ve taken it as a challenge, and I’ve been given the opportunity to show them what I’m capable of, to show them results that perhaps they didn’t expect from me.

What advice would you give to future female engineers?

I’d tell them to follow their passion. They shouldn’t let themselves get discouraged by those who question what they’re studying, that that will bore them. I tell them to fight and research. And if someone tells them no, they should take it as a challenge. Why not?

Alejandra Chávez Santoscoy, the engineer who seeks to improve the diets of Mexicans

Research Professor at Tec de Monterrey

Alejandra Chávez never loses her feet and always returns to her roots. She was born in Guadalajara in 1987 and is a Level 1 researcher in the National Research System. In 2017, she received the Innovators Under 35 Latin America award given by MIT Technology Review.

More than just titles, the most important thing for her is that she can generate value for Mexican society with her work.

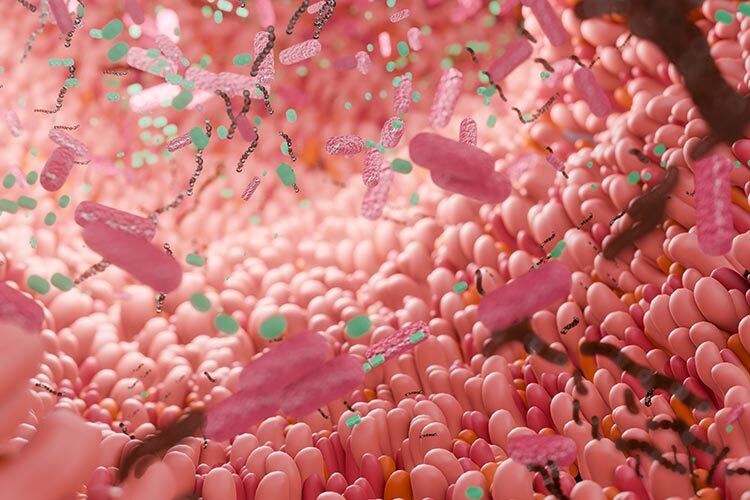

Her research is aimed at using bioactive compounds in foods to help prevent disease, identify molecules of high nutritional value, stabilize their compounds by micro-encapsulation and, with technology, add them to other foods, such as tortillas and sliced bread, to make them healthier.

“I really like to form multidisciplinary teams and collaborate with people who think it can be done, who think there are things that can be done differently.”

What makes you passionate about engineering?

It’s one of the areas that’s given humanity the most solutions to evolve. Sometimes people think that engineering is only mechanical, but it’s actually present in many areas: food, health, medicine, and energy. Engineering is a tool that helps us improve people’s quality of life.

What do you like most about your current job?

That I focus on the development of new foods for the Mexican population. I want to break away from this idea that eating healthy is expensive. We have a responsibility to educate our consumers and provide new foods that are healthy and affordable.

Do you think that being a woman brings something extra to your work as an engineer?

It’s a very difficult question because on the one hand, I would like to say yes because I firmly believe that women have a lot to contribute to the field of engineering and things haven’t been equitable enough for us. However, I don’t want to start that discussion because what I believe in is teamwork. Both women’s and men’s skills are needed to create something that brings value to society. It’s the teams that generate the ideas.

Did you have any role models that pushed you to go into engineering?

Yes. Many women who have taken charge of their lives have been an example for me. One of them has been my mother. I didn’t grow up thinking that women couldn’t access certain areas or that there was a glass ceiling.

My mom is a doctor and a hard worker, and she was a great driving force for me to fight for my dreams. I met many women later at Tec de Monterrey who inspired me, particularly Dr. Janet Gutiérrez who was my advisor for my doctorate degree. She was a role model because I could see that she had her family and her children and that hasn’t prevented her from achieving everything she’s achieved professionally.

What’s been the most challenging project you’ve worked on?

I know that more will come in the future, but at one time it was the founding of the National Laboratory of Genome Sequencing at the Tec. It was very challenging because it involved creating the infrastructure, achieving consensus to purchase the equipment, establishing a sustainable operating model, and connecting with the industry, all of this in the middle of the pandemic. We now have a laboratory with equipment that’s unique in Mexico and we’re perhaps the number two Latin America, which allows us to generate value in research projects into new areas and to link up with other renowned institutes in Mexico, such as the National Cancer Institute or the Federico Gómez pediatric hospital.

What qualities do you think a good engineer should have?

They should be able to generate disruptive ideas and seek solutions that hadn’t been explored before, something fundamental in our times, when doing the same old things has led us to end the planet, to run out of resources.

Good engineers are distinguished by their constancy, methodology, and their capacity to generate multidisciplinary work teams to see problems in an integrated way. And, most importantly, they have a social commitment because they want their work to impact society in a positive way.

What’s the worst thing about being a female engineer?

If you’re a young female engineer, you seem to have all the “flaws.” This happened to me in a public institution where I worked. They believed that I didn’t have sufficient experience or the ability to make decisions. The truth is that engineering is a male-dominated environment and more so in the academic area. What I did was show them that my work had value despite my “flaws.” It helped me to speak very objectively, to go to the facts, to record everything. On the other hand, I’ve realized that I can inspire others as a female engineer.

What advice would you give to future female engineers?

First, I’d say that they need to dream big, that they need to feel confident that they can do it. Sometimes, the main limitation comes from oneself, believing that we’re not enough. Second, they need to find the way forward. They should look for people who think like them, I mean in the sense that they have the same ideals so that they can push each other forward. They should remember that they don’t have to do it all alone. They should rely on the support of others.