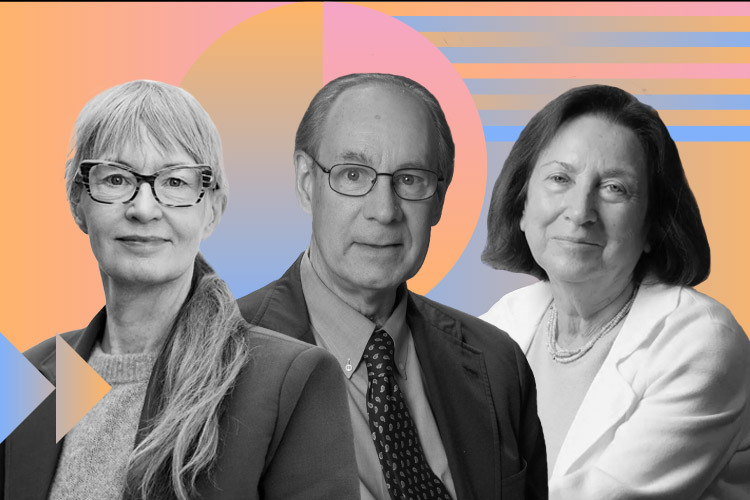

Scientists Joel Habener, Svetlana Mojsov, and Lotte Bjerre Knudsen were awarded the 2024 Lasker Award for their discovery and development of GLP-1-based treatments that have revolutionized the obesity and diabetes new medications.

Recently, drugs developed from their work are being analyzed for possible benefits in treating conditions ranging from addiction to Alzheimer’s disease.

The Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research recognized Habener (Massachusetts General Hospital) and Mojsov (Rockefeller University) for discerning the physiologically active form of the hormone (GLP-1). Knudsen (Novo Nordisk) was recognized for turning it into medications that promote weight loss.

“Obesity is commonly viewed as a failure of willpower, yet for many, diet and exercise don’t cure the problem. Historically, attempts to make safe and effective drugs that help people slim down have fallen short,” explains the Lasker Foundation about this year’s honorees.

The Path to a New Era of Weight Management

In the 1970s, newly trained endocrinologist Joel Habener set up his lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he became interested in studying diabetes.

Typically, glucose stimulates the pancreas to release insulin, which ushers the sugar out of the bloodstream and transports it into cells. In diabetes, the absence of insulin keeps blood glucose levels elevated, while cells are starved of it. While insulin therapy provided one approach, researchers were exploring alternative tactics, according to the Lasker Foundation approach into the scientists’ research.

One such idea was to block glucagon, a pancreatic hormone that raises blood sugar levels, which was thought to potentially help people with diabetes.

Habener used molecular biology to isolate the gene that codes for glucagon although genetic manipulation in mammals wasn’t allowed, so he turned to anglerfish, which had a special organ producing large quantities of glucagon.

Active peptide hormones are released from larger proteins by enzymes cutting at specific places, recalls the Lasker Foundation. In 1982, Habener reported that the anglerfish’s glucagon gene encodes a predicted precursor protein that contains glucagon and, in addition, a second peptide that resembles glucagon.

The same pair of amino acids, lysine-arginine, marked the cutting sites in several hormone precursor proteins. Cutting at those sites would release both glucagon and the second peptide, as explained by the organization.

“A year later, Graeme Bell (Chiron Corporation) discovered that the gene coding for glucagon in hamsters also coded for a version of the second anglerfish peptide, which he named glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1),” adds the Lasker Foundation.

Meanwhile, biochemist Svetlana Mojsov, a researcher at Rockefeller University, identified the amino acid sequence that made up the biologically active form of GLP-1. She eventually demonstrated that this active form could stimulate insulin release in rat pancreases, a critical step toward developing a treatment for humans, according to Nature.

Following these key discoveries about GLP-1, the next step was to turn it into a medication. However, the hormone quickly metabolized, lasting only minutes in the bloodstream.

This is where Knudsen’s work came into play, recalls the scientific journal. As a researcher at the Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, Knudsen and her team realized that regular GLP-1 wouldn’t work as a drug.

Instead, they developed a way to modify GLP-1 by attaching a fatty acid, which allowed the molecule to remain active in the body for longer before being broken down.

This research led to the first long-acting GLP-1-based drug, liraglutide, which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2010 for type 2 diabetes.

“Today, newer variants like semaglutide and tirzepatide, sold as Wegovy and Zepbound, are key treatments for obesity,” Nature notes.

How Do These Drugs Work?

GLP-1 reduces appetite and body weight. With this knowledge, Knudsen and her team continued studying liraglutide and its effects, Lasker Foundation notes. In a key study, obese or overweight participants without diabetes lost an average of 5.5 kilograms over a year.

More than one-third of participants treated with liraglutide lost at least 5% of their body weight, and nearly a quarter lost more than 10%. Liraglutide helps people feel fuller and less hungry, leading them to voluntarily eat less.

To extend its effects even further, after nearly 4,000 attempts to find the right combination of fatty acids and chemical bonds, researchers developed semaglutide. This drug, known under the brand name Ozempic, has an extended effect of up to 165 hours and is a specific treatment for diabetes.

Liraglutide and semaglutide have now paved the way for second-generation drugs like tirzepatide. Unlike GLP-1’s primary effect on the pancreas in diabetes treatment, tirzepatide’s appetite-suppressing activity is centered in the brain. Researchers, including Knudsen, are actively investigating its behavior in this area.

Researchers are also exploring the use of these drugs in a wide range of diseases, including chronic kidney disorders, fatty liver disease, neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, and addictions. “GLP-1-based therapies also offer cardiovascular protection. Earlier this year, the FDA approved semaglutide to reduce heart attacks and strokes in people with pre-existing cardiovascular disease who are overweight or obese,” adds the award organization.

For Obesity, Not Aesthetics

In an interview with AFP, award-winning researcher Svetlana Mojsov emphasized that drugs like Ozempic, liraglutide, and tirzepatide are primarily focused on diabetes.

“The real success is being able to treat obesity, and that’s what we should stick to. I believe they should never be used for cosmetic reasons,” Mojsov told AFP. “I don’t think there’s such a thing as a miracle drug. Every drug has side effects, and we know that when obese patients lose weight, they lose muscle mass, which is serious. But it opens up a frontier,” she added.

These medications should be considered part of personalized medicine, not prescribed for just anyone, and it’s crucial to understand their contraindications.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx