Judith Zavala’s dream is that no Mexican should have to wait years to receive a cornea transplant to restore their vision. The researcher and her team have developed synthetic corneas in the laboratory that are almost identical to real ones and could help thousands of people, but they need more funding to create a viable tissue.

Lab-grown corneas

For the past ten years, Zavala Arcos, a researcher at Tecnológico de Monterrey’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences, and her team, the Research Group on Innovative Therapies in Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, have carefully worked on developing a cultivating system that uses tissue engineering.

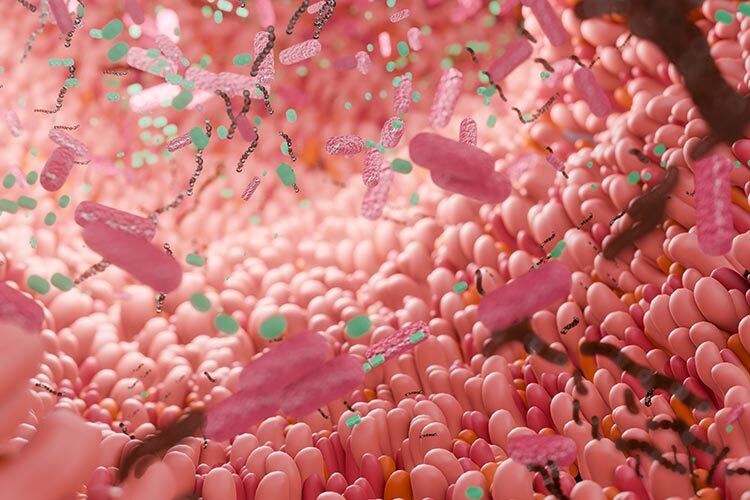

In short, their system consists of extracting cells from the cornea and multiplying them in Petri dishes. These cells are then placed on a synthetic collagen-based membrane. The resulting tissue is just as transparent and functional as a real cornea.

In early 2020, they managed to restore the vision of five blind rabbits by transplanting tissue grown in their laboratory.

The next step was to repeat the trial with more rabbits. Based on those results, they would advance to clinical trials with humans to verify that their tissue is safe and functional.

Unfortunately, the pandemic interrupted their research, and funding ran out from the Frontiers of Science call of the National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt).

Until recently, Judith and her team were still looking for funding through government programs and grants, but with no success.

“Support for science in Mexico is a very gray, sad and discouraging picture,” said Judith Zavala in an interview with TecScience. Fortunately, the researcher has found an alternative.

Limited funding

The cornea is the outermost structure of the eye, located in front of the iris and the pupil. Its function is to let light through and act as a shield to protect the eye from dust and microorganisms that may affect it. When it suffers some damage, due to a blow or an infection, it can develop an opacity that causes partial or total loss of vision known as corneal blindness.

It’s estimated that there are around 2 million new cases of blindness due to cornea damage around the world every year. Fortunately, surgeons have been transplanting that part of the eye for decades, extracting it from post-mortem donations and transplanting it to patients in need.

In Mexico, the cornea is the most transplanted organ or tissue, but because organ donation is limited, patients usually have to wait between six months and two years for their surgery. Each year, less than half of the people who need a cornea receive one. “It’s a very serious problem due to the scarcity of donor tissue,” says Zavala.

Growing corneas in the lab has emerged as an alternative. Led by Jorge Eugenio Valdez García, former Dean of Tec de Monterrey’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences, the project aims to lighten the load on the donation system.

Although the group’s progress was promising, they have not received any funding since 2020.

“All [scientists] are suffering from less funding from the federal government, the support strategies from state governments are very poor, and they are non-existent from local governments,” explains Jorge Valdez in an interview with TecScience.

Escaping the valley of death

Over the last two years, Zavala Arcos and her team have become more and more frustrated. In 2021, the Mexican government published a reform that withdrew the support that Conacyt was giving to private centers and universities, worsening the situation even further.

Browsing the internet, the researcher came across the “IGNITE” call from a company called GRID X based in Buenos Aires, Argentina. GRID X aims to finance science and technology projects in Latin America that transform scientific ideas into companies or initiatives, which in turn generate medicines, products, or technology to solve a particular problem.

Driven by her desire to help people with corneal blindness, Zavala Arcos submitted a proposal. Out of 200 projects proposed, 13 were chosen, including hers.

According to Judith Zavala, after a Shark Tank-style program that pushed them out of their comfort zone and called for them to propose a viable business in six months, they were awarded their first grant on December 4, 2022, and could turn their project into a startup called Ocular Biodesign, under the aegis of Tecnológico de Monterrey.

This first grant will allow them to conduct the remaining preclinical rabbit trials and move on to human clinical trials.

Currently, a preclinical trial costs around 2 to 3 million pesos, while a clinical trial costs around 10 to 15 million, says the researcher. In the academic world, this scientific development stage is known as the “valley of death” as only very few researchers manage to secure enough funding to continue with clinical trials.

If all goes well, after proving the technology works with human cells, the idea is to develop a syringe-like device preloaded with the synthetic corneas. After making a small incision in the patient’s eye, this device will allow surgeons to transplant the corneal epithelium easily and safely.

Their product would be 60% cheaper than the cost of a corneal transplant, which currently costs around 100,000 pesos.

Although donor tissue is still needed to remove cells and place them on their collagen membrane to grow, a single donated cornea could generate up to 10 synthetic corneas.

“In 10 years, I hope to have a beautiful memory of seeing the first patient to receive a transplant of our tissue,” says Judith Zavala Arcos.

Lack of funding for science and technology in Mexico

Historically, science has been underfunded in Mexico. In the last decade, the percentage of GDP invested in science and technology by the federal government has hovered between 0.2% and 0.3%. This places Mexico among the five member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) that invest the least in science worldwide.

According to Valdez García, it is necessary to train scientists from an early stage so that they have the tools to know how to obtain funds for their research. What’s more, they need to work together with the government and civil society.

“That’s the only way we’re going to be able to create a true support culture for scientific and technological development,” he says in an interview.

After having survived the frustration they experienced, Zavala Arcos reflects on the future of science in Mexico. Zavala Arcos thinks the experience at GRID X is proof that science startups are possible and there are more opportunities in Latin America than people think.

“It’s up to the researchers to find alternatives. There’s a world out there to explore,” she says.