In 2016, Manish Kumar was riding a cab on his way to an academic conference when, another passenger he was sharing the ride with told him that his daughter had a urinary tract disease that had no cure. The cause was an antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

“It was a very sad story,” says Kumar, director of the sustainability group at the School of Engineering at the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies in Dehradun, India, and member of the Faculty of Excellence at Tec de Monterrey, in an interview with TecScience.

In that moment Kumar felt an urgency to study the phenomenon and contribute to its solution.

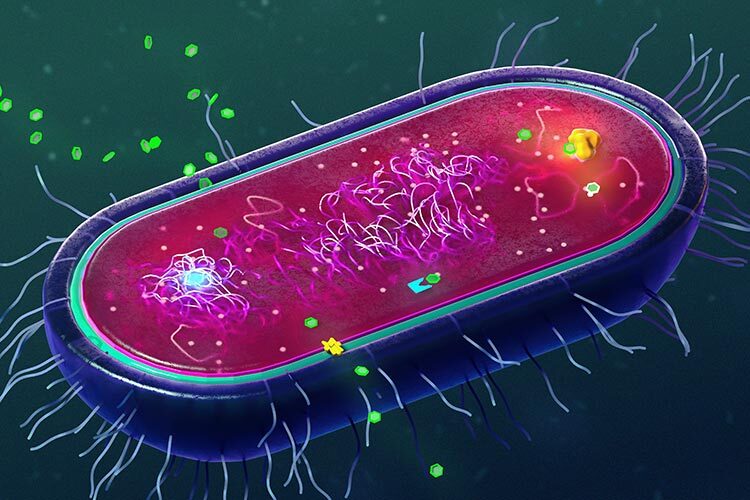

Antimicrobial resistance is a process by which pathogenic bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites develop genetic mechanisms to defend themselves against drugs that are designed to kill them, such as antibiotics, antifungals and antivirals.

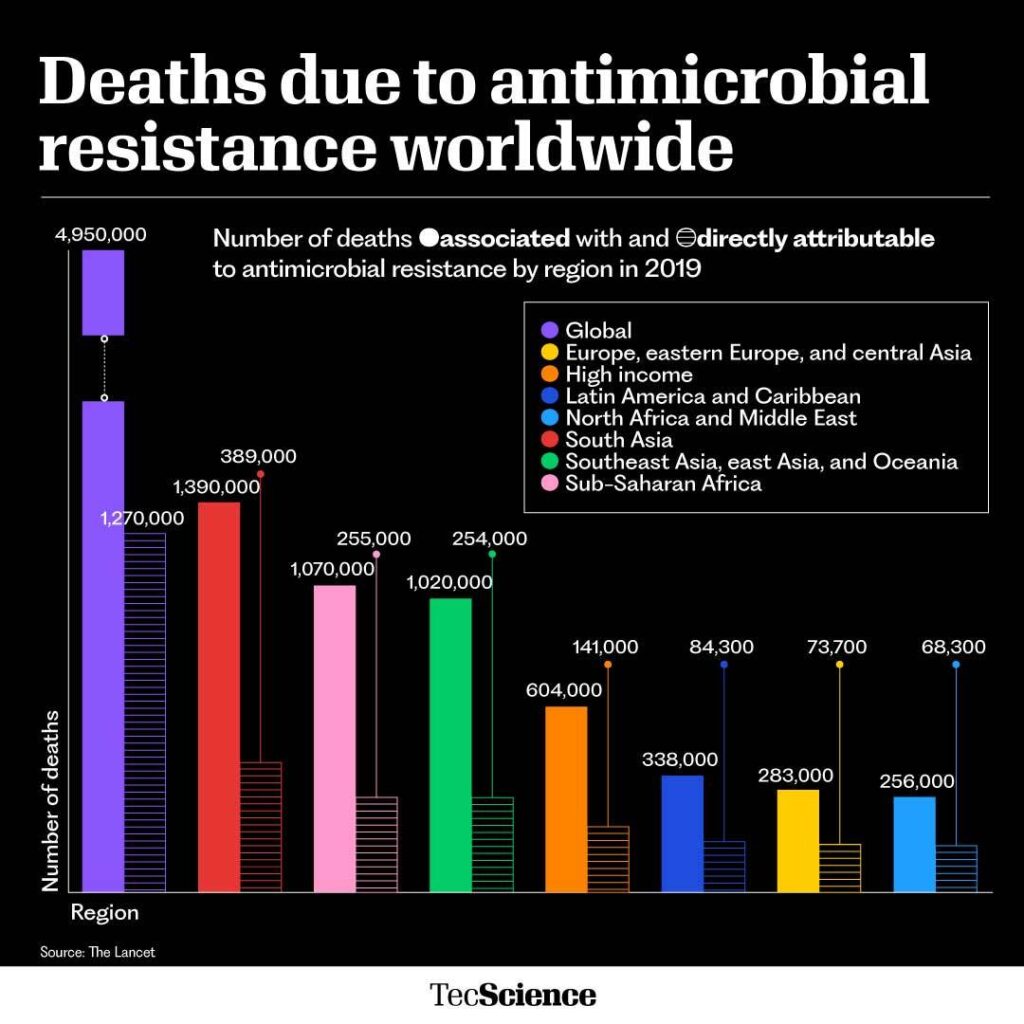

These resistant strains are often called superbugs and are one of the greatest threats to global health. Antimicrobial resistance currently kills 1.2 million people a year worldwide and is predicted to kill around 10 million by 2050.

With this in mind, Kumar has worked for years with multidisciplinary and multinational teams to study the phenomenon from different perspectives and understand how big the problem is, as well as the factors that accelerate the emergence of these superbugs.

“Whenever antimicrobials are used excessively, such as in wars or pandemics, there will be consequences in the spread of this resistance,” Kumar warns.

Pandemics Worsen the Resistance Crisis

Although antimicrobial resistance is a natural process that occurs in pathogens over time, its spread is accelerated by human activities, such as the misuse and overuse of antibiotics (when we don’t complete our course of treatment, for example), as well as their improper disposal.

“Unused antibiotics end up in wastewater and can help spread this problem,” Kumar explains. Because the medication arrives diluted in the water and isn’t enough to kill them, they develop resistance more easily.

Throughout his career, Kumar has studied the contamination of different bodies of water and wastewater, so it seemed natural to him to study the prevalence of superbugs in rivers, lakes and treatment plants.

In one of their studies, they measured the amount of non-resistant bacteria and resistant bacteria in treatment plants in India and Sri Lanka, in South Asia, and found that the treatment process reduced the amount of non-resistant bacteria, but increased resistant bacteria.

“There is a saying that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” says Kumar.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, the team returned to the same places where they had already measured the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and found that, in all cases, they had increased in quantity.

According to their studies, this could be because, although this particular health crisis was due to a virus, many people turned to antibiotics to treat additional infections or simply to prevent them.

“In places like India, regulations for buying antibiotics aren’t that strict and anyone can buy them without a prescription,” says the expert.

With this and other pandemics, new infections and health problems arise that urgently need medication, leading to an increase in their consumption.

In Portugal, the demand for pharmaceutical products increased by 60% in just one week, after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the last pandemic.

Wars Also Make it Worse

Just as the pandemic accelerate the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens, so can wars.

“Battle wounds and diseases resulting from the unhygienic conditions that happen in wars require antimicrobials to be treated,” says Kumar.

Antimicrobial overuse, the destruction of hospitals and health services, and the interruption of treatments due to displacements to safe areas trigger drug resistance.

In a recently article, titled Wars and Pandemics: Accelerators of 21st Century Antimicrobial Resistance?, Kumar and colleagues explain that –historically–, wars have increased the use of antibiotics globally.

Before World War I, antibiotics had not been discovered, until on September 28, 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, which became the first antibiotic used to treat diseases.

“Resistance to penicillin was first described after World War II,” says Kumar.

According to the researchers, this cannot be a coincidence. Their hypothesis is that both pandemics and wars are two of the biggest accelerators of antimicrobial resistance.

Some Measures to Attack the Problem

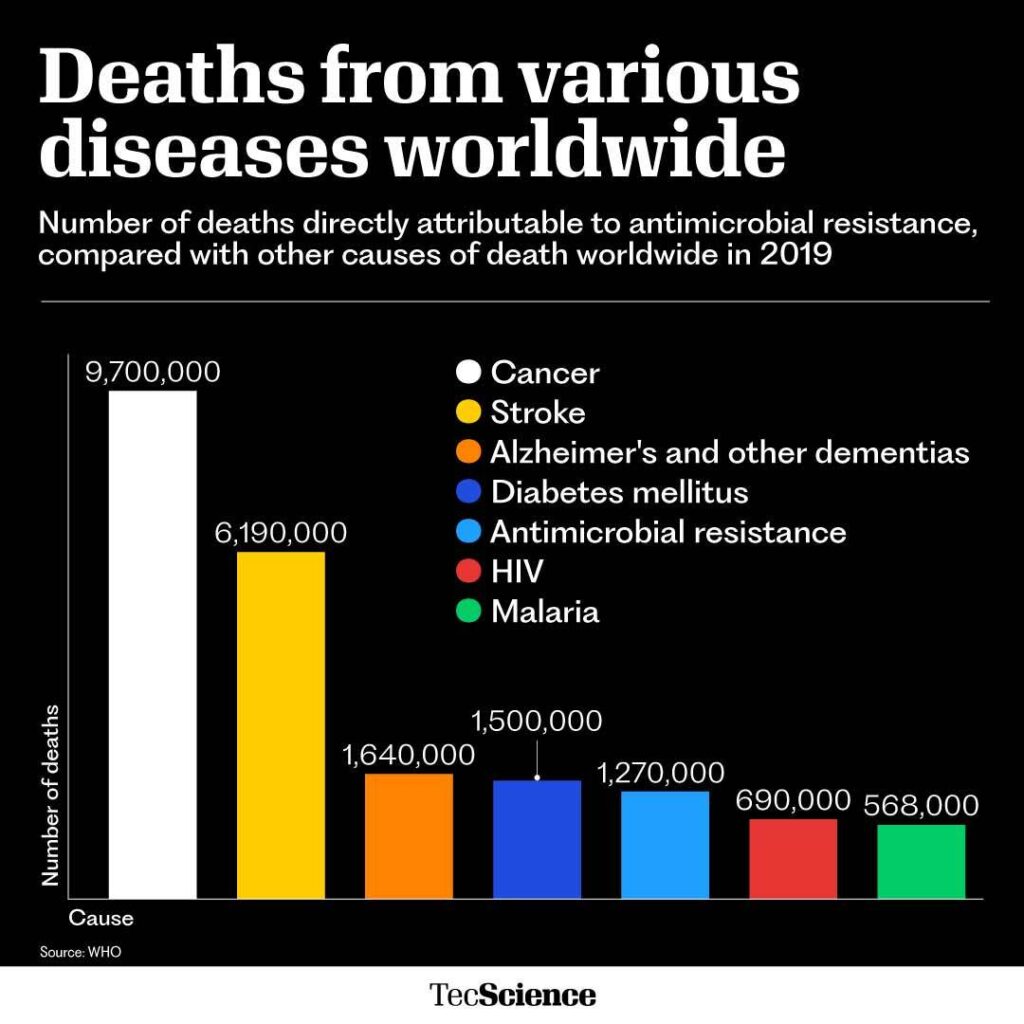

Although antimicrobial resistance may sound like a distant problem, the reality is that today it kills more people than malaria or the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

This is even more worrying because there is currently a gap in the discovery of effective antibiotics. The last one that could be introduced as a treatment was discovered in 1987.

Therefore, researchers and health organizations around the world have warned that we must take drastic measures to stop the problem and not allow it to continue growing.

“We have to make a collective effort. The world is now a global village in which we can all travel, spreading diseases and superbugs,” urges Kumar.

Some of the measures suggested by experts are:

- Establishing strict control in all countries of the world for the purchase and use of antimicrobials

- Reducing their use to cases where they are strictly necessary

- Avoiding overprescription at all costs

The media, schools and universities must make an effort to alert people about the problem so that, even if there are no regulations, they avoid overusing them and question their doctors when they want to prescribe them.

Governments and pharmaceutical companies must also provide a plan for the proper disposal of unused antimicrobials to ensure they do not end up in wastewater, rivers or oceans.

“If some country thinks it is not their problem, they are wrong, we are all at risk and we need to pursue one health, one future,” says Kumar.

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx