Eradicating the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the dream of many doctors and scientists who have dedicated their lives to studying it and treating the people who contract it. However, achieving this will require efforts on many fronts, including creating an effective vaccine, bringing existing treatments to all those who are infected and eliminating the social stigma associated with it.

“We have to believe that we can do it,” says Bruce Walker, a physician and scientist who specializes in infectious disease and director at the Ragon Institute.

Walker finished medical school at the time when a new disease –now called acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) caused by HIV– began causing deaths among the United States population.

At that time, in the late 1980s, contracting HIV –a sexually transmitted virus– was like a death sentence, since it was still unknown to science.

“I decided that instead of treating patients exclusively, I would also study their immune response in the lab,” Walker recalls.

Now, after more than 30 years of continuous research, him and many scientists around the world have come to deeply understand the virus and the situation is no longer as bleak as it used to be.

Today, treatments that guarantee the survival of those who contract it are available and vaccines that could prevent it from spreading are being created.

“The vaccine that is being developed here at the Ragon Institute is going to be tried in people this spring,” Walker says. “We are optimistic…but we could be wrong.”

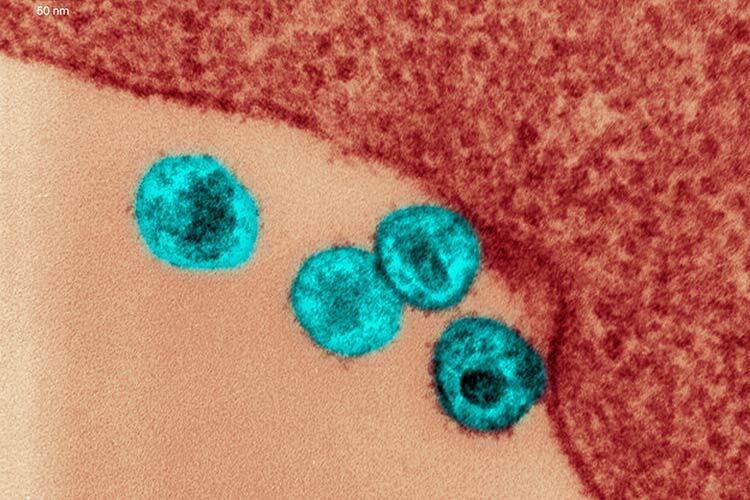

HIV: A Virus That Mutates at Unimaginable Rates

With the Covid-19 pandemic, a global effort showed that creating a vaccine can be very fast, however, for decades, researchers around the world have sought to create one against HIV unsuccessfully.

“With Covid-19, we had to create new versions of the vaccines for the different variants because the virus mutates,” says Facundo Batista, a researcher who specializes in the immune system and scientific director at the Ragon Institute. But HIV has one of the highest mutation rates known of any virus.

“The HIV variants that develop in a single person are equivalent to all those that were generated from the influenza virus around the world during the 1996 pandemic,” explains Batista. When our body begins to understand the virus and mount a battle against it, it has already changed multiple times and become unrecognizable.

That is why finding a vaccine against it is so difficult, but scientists have not given up. “We are trying to train the immune system with these vaccines to hit the virus where it’s most vulnerable,” Walker says.

Elite Controllers and One HIV Vaccine

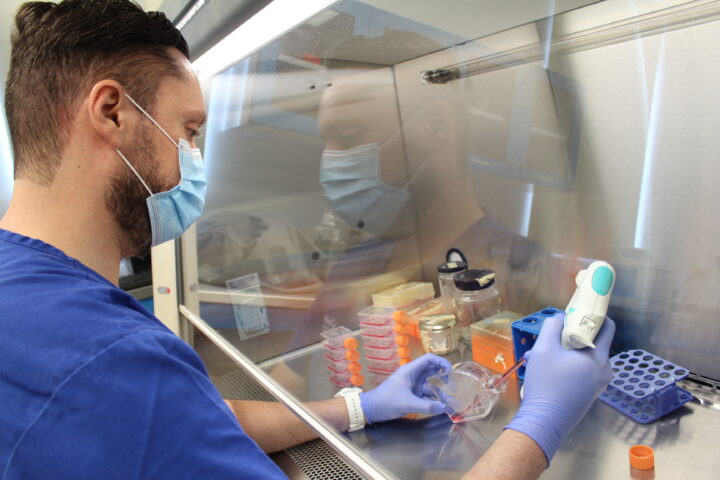

A group led by Gaurav Gaiha, of which Walker is a member, is working on creating an HIV vaccine that induces the immune system to create a special type of killer T cell that is capable of detecting a part of the virus that cannot mutate.

This type of killer T cell was discovered by Walker and his mentors in 1994, when they received a patient who had contracted HIV 15 years earlier, but had not developed AIDS. He was perfectly healthy without having taken antiretroviral drugs or any type of medication.

After years of study and finding other people who managed to naturally control their HIV infection -known as elite controllers– the group of experts discovered that, for reasons still unknown, there are some who become infected, but manage to keep the levels of the virus to an undetectable level without needing to take drugs. Only one in 300 infected people is capable of this.

All humans have killer T cells, which are part of our immune system and kill infected cells by detecting fragments of viruses or bacteria inside them. Elite controllers have a special type that allows them to detect a part of HIV that cannot mutate.

“We still don’t entirely understand why some people are so fortunate as to get this particular flavor of killer T cell,” says Walker. “But the fact that they exist has to give us hope that we can overcome the devastation of this disease.”

The vaccine they are working on will not only be able to prevent HIV infection, but also serve as a treatment. A first version of it will be tested on humans in the spring of 2025, however, the researcher estimates that it will take another 10 years or so for it to reach the market.

The Mother of All Vaccines

At the same time, the laboratory led by Batista is part of a multi-institutional consortium that is working on another vaccine that could prevent HIV infection.

This one works by stimulating the immune system to produce a type of antibody – called broadly neutralizing- that is capable of recognizing and eliminating between 70% and 90% of HIV variants.

To achieve this, the researchers designed a vaccine component that interacts with B cells (white blood cells that create antibodies) of the immune system and induces it to create them.

Batista’s laboratory tested a single dose of this component in animal models and found that it increased the activity of this type of antibody, neutralizing some of the HIV variants.

“Slowly this puzzle is coming together, but we are still in an early stage,” says the researcher.

To get the final vaccine, new components need to be designed so that, together with the one that has already been created and tested, they can eliminate most of the virus models in animal models and then human trials, which will take about 10 or 15 years.

In the future, the idea is that both vaccines can be used simultaneously in people to give them powerful protection.

“I call it the mother of all vaccines,” says Batista. According to him, if they manage to create them, it will be much easier to make vaccines against other difficult diseases, such as tuberculosis, in the future.

Obtaining the HIV vaccine is especially important to end the disease in Africa, where it has been especially devastating.

“In developed countries and parts of Latin America there are drugs that can control the infection, so people stop being afraid” says Batista. “But there is no doubt that we need a vaccine.”

How to Eradicate HIV

In the future, to truly eradicate HIV, we will not only need to develop efficient vaccines, but also need expand prevention -that is, pre-exposure prophylaxis (known as PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (known as PEP)- and the existing treatments so that they reach all infected people and those who are most vulnerable to contracting the virus.

Both PrEP and PEP are medications that are administered to people before or after a risky sexual encounter or situation, to prevent infection from occurring.

“In Mexico, PrEP and PEP come in the form of a pill that mixes two are medications that trick the virus and prevent it from creating new copies,” says Eduardo Pérez, an internist physician at TecSalud and vice president of the HIV Committee of the Mexican Association of Infectology and Clinical Microbiology.

People who develop AIDS can also be treated with these drugs to control the disease and live a healthy life. “Today, in Mexico, the life expectancy of a person diagnosed with HIV is between 50 and 60 years after the diagnosis,” says Pérez.

But, for all this to really work, it is essential that the social stigma that has surrounded HIV/AIDS for years disappears. The fact that people are afraid to know if they are infected or not is worrying, because it means that there are some who carry the disease without knowing it, becoming a source of contagion. “In Mexico, two out of 10 people living with HIV do not know they are,” warns Pérez.

Thus, eradicating HIV will require prolonged efforts by researchers, doctors, pharmaceutical companies, governments and societies. “I think we can become smart enough to figure out how to do it,” says Walker.

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx