Living through adversity during childhood leaves traces in the body and mind of those who suffer it until they are adults. Although it is well known that these experiences cause a greater risk of having different diseases, we know little about the mechanisms behind this.

“Sometimes, it’s a bit difficult to understand that these events can leave a mark [on us] forever,” says Patricia Silveira, a researcher at the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University, Toronto, in an interview with TecScience.

Although it may sound hard to believe, discomfort during our first years of life can change our cells and organs.

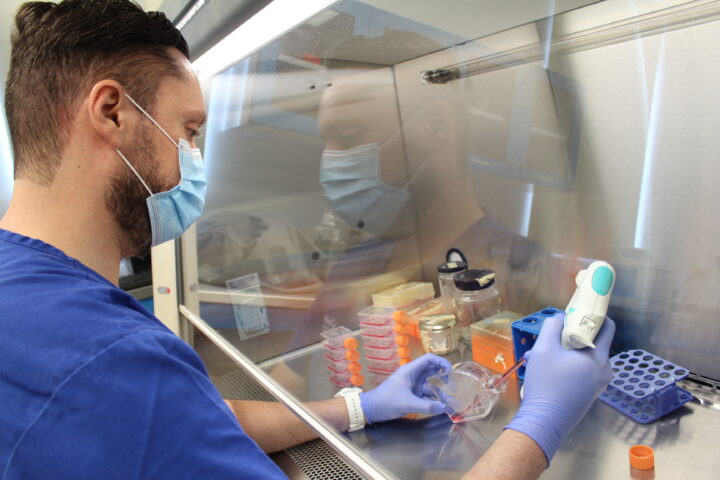

For years, Silveira and her team have dedicated their research to understanding childhood adversity’s short- and long-term effects on the health trajectories of those who experience it.

Using animal and human models, they have found multiple cellular, molecular, neurobiological, epigenetic, and behavioral effects that explain how adversity, abuse, and chronic stress during childhood impact human life.

Studies On Adverse Childhood Experiences

These adverse experiences are diverse and range from physical abuse and emotional mistreatment to living in marginalized communities. This increases the presence of stress hormones such as cortisol and cortisone, affecting multiple organs and systems.

Recently, their research has shown that if mothers experience adversity during pregnancy –known as prenatal stress– it can impact their children’s eating behavior in the future.

In an animal model, they found that adults born to stressed mothers have a greater preference and are more impulsive toward foods high in fat and sugar.

“The effect seems to be more marked in females than in males,” explains Roberta Dalle, a researcher in Silveira’s laboratory.

These eating patterns could be linked to the increase in metabolic diseases, such as type two diabetes, which have been observed to increase in people who experienced early adversity.

They confirmed their findings with animal models in studies with Canadian and Brazilian adults they observed throughout their lives. In both cases, they saw that those who experienced prenatal stress showed the same preference for sweet and fatty foods.

Changes In Our Brain and The Way Our Genes Are Expressed

To delve deeper into what is behind these changes in their eating behavior, the group studied the brain of their animal model. In doing so, they found that individuals with prenatal stress had different dopamine release patterns than those who had not experienced this type of stress.

“Dopamine is a neurotransmitter associated with motivation, reward, sleep regulation, mood and learning, as well as impulsivity and control,” explains Silveira.

This differentiated release was detected in brain areas that inhibit risky behaviors, such as the frontal cortex.

In another study, they found that prenatal stress also impacts insulin levels –a hormone produced in the pancreas– and that this, in turn, influences the release of different neurotransmitters, such as dopamine.

“The way these individuals respond to food seems to be very much an interaction between peripheral metabolism and central pathways of the brain,” says Silveira.

Bad childhood experiences also seem to affect how our genes are expressed, known as epigenetics.

In a recent study, a group of researchers found a decreased expression of the NR3C1 gene, a receptor for cortisol, cortisone, and corticosterone, in a brain region of suicide victims with a history of childhood abuse.

These findings echo the fact that there appears to be a coexistence between mental illnesses, such as depression and metabolic diseases.

“People who have type two diabetes have more risk for food mood disorders and the other way around too,” explains Silveira. Currently, they are trying to understand how prenatal stress and childhood adversity increase the risk of this coexistence.

How Much Stress Is Too Much Stress?

Although many studies on childhood adversity have focused on trauma, there are more subtle levels that also have an effect.

“Lower socioeconomic status or safety levels in a neighborhood are also adverse experiences and appear to have a cumulative effect,” explains Silveira.

Although it is essential that, as a society, we take care of children so that they live fully, overprotecting them is not the answer.

“If you live in nature, you are going to have stress and this is normal, our body is prepared to respond to it, the problem is when it’s chronic,” says Dalle.

Eliminating any worry or not allowing them to do activities for fear of getting hurt adds stress. Something similar to what happens when we get sick from cleaning ourselves and our surroundings excessively.

The Future of Childcare

In the years ahead, the group seeks to understand what puts some people at greater risk of experiencing the consequences. “Living through adversity does not mean you will develop this or that disease for sure,” explains Dalle. Studying this could encourage prevention programs explicitly aimed at those who are most vulnerable.

For them, the evidence they have found is an opportunity to improve as a society and guarantee that children live safely.

“I think the message that we get is that childhood is a very important time and that the support is in place, even before birth,” reflects Silveira.

With this information, they wish prevention, prenatal care, support from well-trained professionals, and timely interventions to reduce the impact of these experiences on those who have already lived them to be promoted.

Through science, we could even measure which interventions work or what factors are associated with some people responding to them while others do not. “Could we have markers for effectiveness?” Silveira asks.

While they find the answers to these questions, the researcher assures that their work will continue and that they seek to contribute to a society that takes better care of their infancies.

“That’s why we are here, to study these things and propose new solutions,” Silveira concludes.