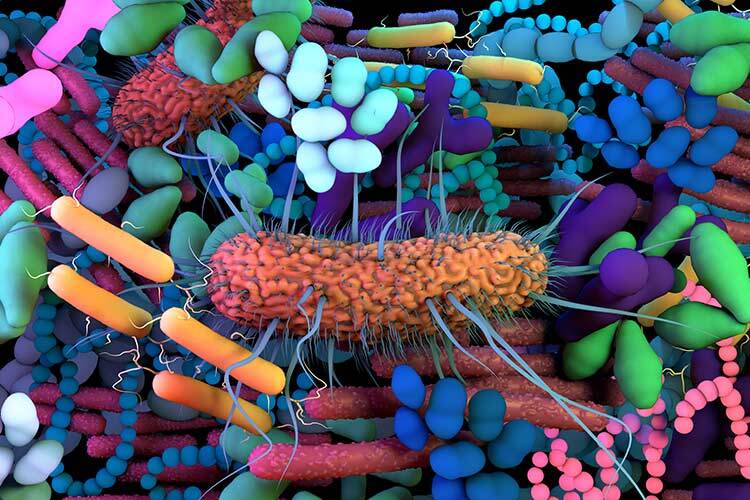

The risk of contracting HIV may increase depending on the composition of the vaginal microbiome –the group of microorganisms that inhabit the female genital tract– of women. One species, Lactobacillus crispatus, seems to have a protective effect when it is abundantly present.

Although we usually associate the word microbiome with that of the digestive system, there is increasing evidence that the vaginal one could play a crucial role in various diseases that affect half of the human population.

“In South Africa, we have studied how this microbiome impacts the risk of HIV acquisition, as well as how it may affect pre-term birth, fertility, and cervical cancer,” says Douglas Kwon, an infectious disease doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General) and researcher at the Ragon Institute, in an interview with TecScience.

For more than a decade, a group of researchers led by Kwon has focused their efforts on understanding the basic biology of the vaginal microbiome to learn about its relationship with different diseases and, eventually, propose interventions and treatments that improve the quality of life of women.

To do so, 12 years ago, they established the FRESH study, an acronym for Females Rising through Education, Support and Health, in Durban, South Africa.

According to the expert, this place is the epicenter of HIV, where 60% of women between 20 and 30 years old have been infected with this virus, mainly due to social and economic factors.

“Our goal is to understand what are the factors affect a woman’s biological risk of acquiring HIV and whether we can use that information to create better methods to prevent it,” Kwon said.

FRESH, Understanding, and Empowering South African Women

FRESH is not only a scientific study where vaginal microbiome and blood samples are taken from women of different ages but a program where they learn about HIV prevention, health, science, and professional tools.

“Women come twice a week for 10 months to the site and learn a lot of things, such as how to use a computer or write a resume,” says Kwon. “We are very proud that over 85% of the graduates go on to either complete their high school, get a job or an internship.”

Among the findings of their studies is the fact that in South Africa, only between 25 and 30% of women have a vaginal microbiome dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus, while the other 70% have a microbiome abundant in a mixture of anaerobic bacteria.

“These bacteria are very similar to communities you would find in bacterial vaginosis, a common infection in women worldwide,” explains the researcher.

In general, these researchers and other scientific groups have found that a vaginal microbiome dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus is an indicator of a healthy vaginal tract. In the United States and Europe, 90% of white women have a microbiome where this species predominates.

“Studies in Asia and Latin America show that more like 50% of women have Lactobacillus communities,” says Kwon.

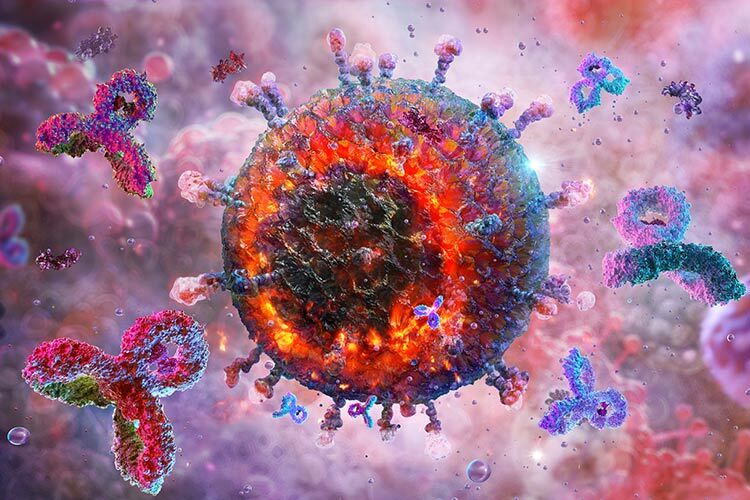

Women who have a microbiome where anaerobic bacteria abound in South Africa have a risk four times higher of acquiring HIV than those who have one dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus, even when controls are made to rule out the influence of risky sexual behaviors or other factors associated with HIV contagion.

The Relationship Between the Vaginal Microbiome and the Immune System

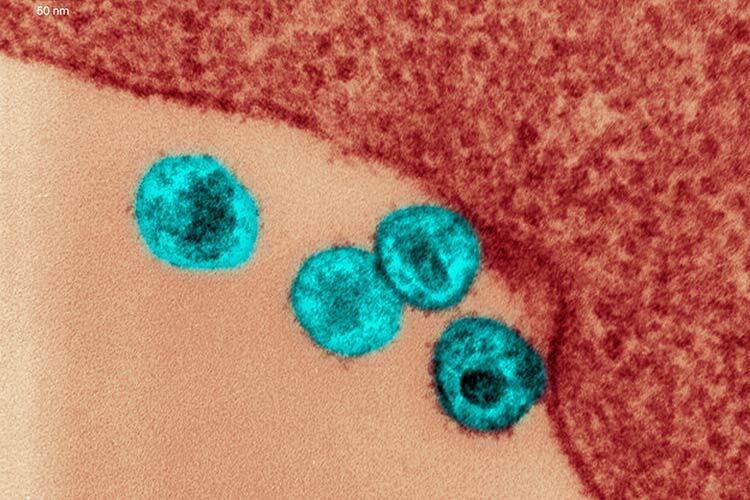

According to Kwon, part of the explanation behind the association between the vaginal microbiome and the risk of acquiring HIV lies in the relationship between the former and the immune system of women.

The presence of anaerobic bacteria increases the number of cytokines –immune system cells that grow in the face of infection– and CD4 cells, a type of white blood cell, in the vaginal tract, which leads to a state of generalized inflammation.

Inflammation itself could facilitate the entry of HIV into cells, but there is also the fact that CD4 cells are the main target of HIV.

Having a microbiome where anaerobic bacteria predominate increases the presence of these cells and, in turn, the risk of becoming infected.

“It’s like if you have a spark and a big pile of dry grass, it is more likely for that spark to catch fire,” says Kwon.

Among some of their next objectives is to understand in depth the cellular and molecular mechanisms, as well as the signaling pathways that underlie this phenomenon.

They also seek to take the studies to other parts of the world to understand why the vaginal microbiome varies so much between different geographic regions, as well as to continue studying the relationship of the vaginal microbiome with premature birth and cervical cancer.

Vaginal Probiotics of the Future

In a parallel line of research, the group has tested the use of vaginal probiotics to see if they can increase the presence of Lactobacillus crispatus in women who do not have it.

In a first trial, they used an intravaginal probiotic composed of a single strain of this bacterial species. What they found was that it did increase the population of it, but only for a short period of time.

Now, they plan to use a probiotic composed of various strains of Lactobacillus crispatus that come from American women and South African women.

“The strains were selected based on specific genomic characteristics ,” says Kwon.

They also plan to test whether a vaginal microbiome transplant could help. The idea is to take secretions from a clinically healthy woman and transplant it to an affected women to see if it can increase the Lactobacillus crispatus population on a sustained basis.

According to the researcher, in the the intestinal microbiome world, probiotics show positive results while patients are taking them, but a sustained effect has only been shown in fecal transplants.

“We are trying to see if a similar concept might be true for the vaginal microbiome,” says the researcher.

The results of both studies will be ready in the next few years.

We Need Better Health Care for Women

For Kwon, the relevance of studying the vaginal microbiome of women in South Africa is not only important to reduce their risk of contracting HIV and other diseases, but also because it lays the foundation for improving health care for women everywhere.

“I think that, in general, there has been less attention paid to women’s health overall and the vaginal microbiome field is behind the gut microbiome field,” says Kwon. “But we have very clear evidence that it actually directly impacts on a number of really important health outcomes for women.”

According to him, a clear example of how women’s health has not been a priority is the treatment of vaginal vaginosis. “After standard treatment with antibiotics, over 60% of women recur after six months, that is like a terrible treatment, and there has been no innovation in that area in more than 40 years,” he says.

Going forward, as they deepen their knowledge about the vaginal microbiome and its relationship with women’s health, the researcher hopes that his group can propose new and better tools to prevent different diseases that affect us.

“This is especially important for low- and middle-income countries,” says Kwon.

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx