Imagine living in a city where there is river pollution and garbage that ends up in major lakes. A possible approach might be to simply start cleaning up, but another possibility could be to use research living labs.

International organizations of scientists and experts are going a step further, relying on science and innovation to analyze the problem and seek answers through live research spaces.

In 2014, the Tec de Monterrey launched the “Distrito Tec” program, an urban revitalization effort centered on its Monterrey campus.

In the years following, it has led and produced many live research initiatives that combine research, data, and interventions.

Research Living Labs

These spaces are known as Research Living Labs, which are spaces that allow researchers to interact across disciplines in the context of urban planning to discover and work on ideas for the regeneration and improvement of urban areas.

“They allow for the creation of ideas as well as their testing to see if they work. If they succeed, they can be enlarged or taken to other cities. They allow for implementation, patenting, or exportation,” claims Roberto Ponce, a research professor at the School of Government and Public Transformation and the leader of a research group called “City Science.”

According to Rolando Cantú, engagement coordinator at the Center for the Future of Cities, they are now working in four of these places.

“Distrito Tec,” is one of them, focusing on urban regeneration in the communities and surroundings around the Monterrey campus.

“Distrito Tlalpan” is another project similar to “Distrito Tec,” but adjacent to the Mexico City Campus and with a greater focus on water management.

The third is the “Campana Altamira” project, which is located inside the urban boundaries of “Distrito Tec” and focuses on the restoration of urban areas in the same-named neighborhood, which is facing different socioeconomic issues.

The fourth project, located inside the “Campana Altamira” program is “Arroyo Vivo,” which focuses on the remediation (trash removal), recycling, and restoration of places in the “Arroyo Seco,” a river in San Pedro Garza Garcia, Nuevo León. It runs into the “Ro La Silla” in South Monterrey and then through multiple dams before reaching the ocean.

Arroyo Vivo: A Management and Cleanup Laboratory

This initiative began a few years ago as part of the World Wide Fund for Nature’s (WWF) “Mexico Climate Action Alliance,” bringing together institutions, businesses, government agencies, and civil society organizations.

“Our mission is to clean and restore this space, which has been affected by pollution and waste, and turn it into a healthy place for the community,” says Sheila Quintana, project manager of the “Arroyo Vivo” Project.

However, efforts to improve these areas are not completely reliant on the ideas or suspicions of one or more persons, but based on research and data.

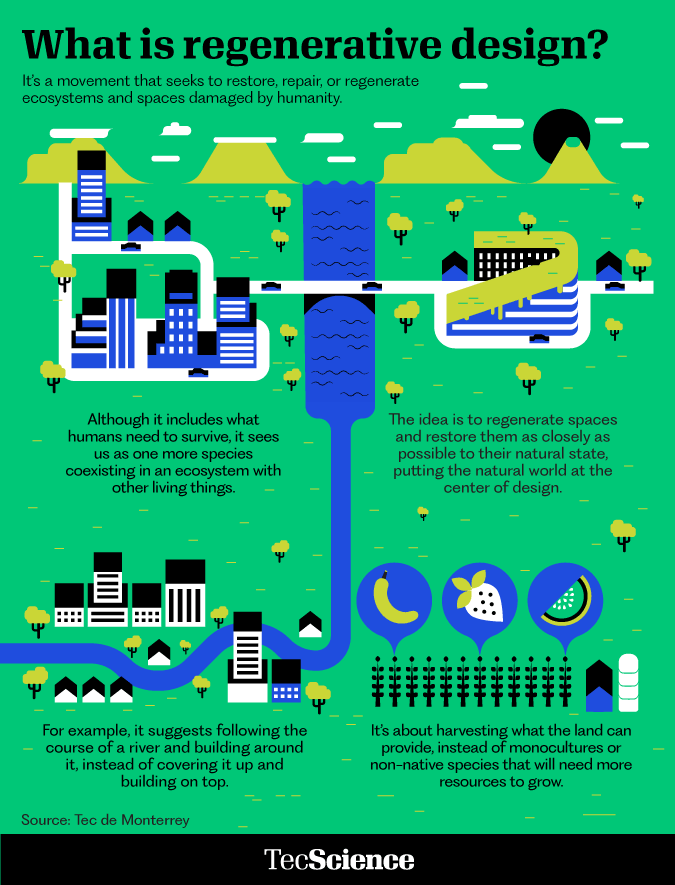

For example, Alejandro Echeverri, a renowned Colombian architect, and Rob Roggema, a recognized researcher in regenerative design, both of whom are members of the Tec de Monterrey’s “Faculty of Excellence” program, are collaborating on this project.

Quintana notes that these collaborations with professionals and government entities have been critical to the project’s progress since they provide opportunities for their studies.

“Robb, for example, has concentrated on water body regeneration. Approaching him aided us in identifying solutions not just inside the river but also on a wider scale,” says Quintana.

“Echeverri had significant experience in the intervention of the Medellín River, so he comes and shares his work experience, helping us be better prepared,” she says.

One of the current initiatives under this program attempts to collect data and study the river region using technology.

Cantú and Quintana discuss the potential use of technology to collect comprehensive photographs that can identify the origin of rubbish poured into the river and pinpoint where it ends up, whether in the same river, a body of water, or the ocean.

Actions Based on Data, Data, and More Data

Ponce illustrates how recording, tracking, and identifying garbage in the “Arroyo Seco” may help with cleaning and maintenance activities.

This is not the first time a project of this nature has been undertaken. Ponce worked on a project named “Crowd-counting” at “Distrito Tec,” following the building of “Parque Central del Tec,” a public space in front of the institution.

Computational vision cameras are used to count visitors to the park, determine park usage trends using heatmaps, and generate statistics on activities at different points in time.

Another comparable project is a data-driven urban growth simulator that can be used to model a city’s growth, allowing for the simulation of multiple urban development scenarios and evaluating the impact of activities inside the city.

“There are decisions in a city that require billions of pesos in investments, and once built, they cannot be demolished or reversed. Projects like these can help you do it with as much evidence as possible,” Ponce explains.

The urban growth simulator takes into account the layout of a city, its transportation, the influence on property prices, and the green spaces around it.

“I believe that one of the most remarkable aspects of these projects is that they are approached from the bottom up and in an interdisciplinary manner. You have students and professors from engineering, urban planning, and the Center for the Future of Cities,” Ponce explains.

“Research is fundamental in the field of city science for making informed decisions, working on important issues, and optimizing projects to have a greater impact and provide people with a more dignified life,” Cantú concludes