Obesity can’t be cured by just running or doing exercise, explains Carolina Solis-Herrera. Nor can “willpower” make it go away.

An integrated approach based on four central pillars is needed for people to lose a sufficient percentage of weight: nutrition education, medication support, cognitive behavioral therapy, and, yes, physical activity.

Solis-Herrera is the Endocrinology Division Chief at the University of Texas, where her research focus is diabetes mellitus.

“There are diseases that cause the body to intensively produce hormones such as ghrelin, which makes people always feel hungry. It’s not that they don’t have any willpower, but their brains and bodies aren’t receiving the signal for satiety.”

The researcher, who took part in the International Conference on Obesity Research at Tec de Monterrey, spoke to TecScience a few days before on how the narrative around obesity should be changed and the medical community should treat patients through a transdisciplinary, longitudinal, and empathic perspective.

What Is Obesity?

Obesity is a chronic inflammatory disease that requires long-term treatment, an approach involving a shift in the medical paradigm.

According to Solis-Herrera, conditions of obesity and diabetes have increased exponentially in recent years.

Despite estimates that half the population has this condition, only 1% receives appropriate treatment designed specifically for each patient and not −exclusively− to improve symptoms and comorbidities.

As part of her line of research, she has detected the presence of around 200 metabolic and mechanical complications, such as myocardial infarctions, embolisms, sleep apnea, cases of dementia, Alzheimer’s, and psychological, respiratory, and even sexual problems.

“The main finding is simple: obesity increases your risk of mortality by 30%, which practically means that someone with a high Body Mass Index lives 10 years less. Although that -rightfully- scares people, our job isn’t to carry on scaring or blaming them without providing support,” she says.

The Solution Isn’t Eating Less and Doing More Exercise

Solis’s new narrative starts with the physiology of patients with obesity; this approach focuses on people’s bodies beyond their eating and exercise habits, putting the diagnosis and treatment of factors from the obesogenic environment at the center.

“Before, at medical school, we talked a lot about ingesting energy and expanding it. In simple terms, calories go in, more calories go out than those consumed, and that’s all there is. Someone who’s overweight has to maintain that deficit to lose weight. However, that’s not what happens.”

The specialist explains that the genetic component is important, as there are genes that release a greater number of hormones that cause an increase in appetite, genes that don’t allow the satiety center to work properly, and even a hyperactive mesolimbic system (a circuit that generates dopamine).

Besides directly influencing weight increase, the role that genes play in people with obesity can be a determining factor in losing an adequate percentage of weight. According to Solis-Herrera, the problem is that patients are subjected to scrutiny if their genes work against them.

This is how the narrative tends to make these people develop a sense of guilt, as difficulties with losing weight are framed -frequently by doctors themselves- as a lack of willpower, when the root cause is not connected to motivation or the amount of food ingested.

“There are many components that lead to patients who eat around 1,500 to 1,800 calories being very thin, while other patients who eat 1,200 calories per day are struggling not to put on weight. It’s not all about what goes in and what comes out; the first step in the new narrative is to destigmatize obesity and to destigmatize ourselves.”

Don’t Stigmatize Medication

Solis-Herrera says that both obesity treatment and research need a multidisciplinary approach with the addition of complementary perspectives that not only focus on people losing weight but also on maintaining the new weight in the long term and being able to regain their physical and mental health.

“There are now multiple studies showing that if you just give people medication but don’t give them nutrition and lifestyle classes, make them do exercise, and you don’t see how they are cognitively, they lose less weight, don’t lose anything, or put it on again if they lose it.”

That’s why this multidisciplinary vision involves four central pillars: nutrition education, medication support, cognitive behavioral therapy, and physical activity.

With the combination of these four, the expert has seen results with patients who have lost around 20 kilograms without putting them back on in the long term. This comes in addition to reducing side effects such as back pain, high blood pressure, and preventing diabetes, as well as enabling them to regain confidence, enthusiasm, and motivation to carry on.

It’s essential for the new medical discourse to recognize the efficacy of medication that assists with weight loss without seeing this as an option that “doesn’t need that much effort,” as a considerable number of patients with obesity are genetically predisposed to accumulating more fat and retaining more weight than others.

Although pharmaceuticals such as (injectable or oral) semaglutide can help achieve beneficial results in most patients, Herrera-Solis recommends accompanying these with a diet plan adapted to the body’s needs under a regime of medication, exercise, and psychological monitoring to prevent a rebound curve.

She acknowledges that the price and lack of access to this type of medication has limited its use for patients outside the United States and even Mexico. However, she says that investment in treating obesity as a priority is 50% less costly than first treating comorbidities such as diabetes.

Will There Be a Cure for Obesity in the Next Five Years?

Solis-Herrera’s future research is focused on achieving a specific cure for obesity, extending primary prevention in schools and within families, and making generational changes and strategies to combat the condition that are consistent between countries.

Some of these goals are linked to cultural and generational changes that can work more in the long term than in the short term to prevent the next generations of teenagers and young adults from having overweight and obesity problems.

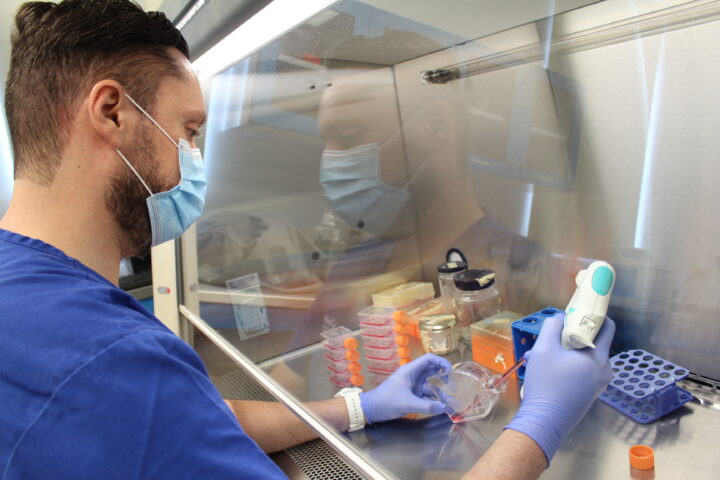

However, researchers in the area continue seeking a future molecular and pharmacological “cure,” attempting to find new areas and receptors that can be explored with the aim of creating medication that is more effective at treating obesity because it has been specifically created to do so.

“On the one hand, we’re focusing on primary prevention, while secondary prevention is on the other. Later on, with precision medicine at a genetic level, we expect to find which genes can be modified so that you don’t turn into someone who absorbs more calories and puts on more weight if you have them.”

With increasing numbers of patients capable of losing at least 3% of their body mass, thus reducing the side effects of their conditions, Solis-Herrera can already see a more successful path towards a future with fewer cases of risk and premature deaths, hoping to achieve the famous “cure” for obesity eventually.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Get in touch with our content editor to find out more at marianaleonm@tec.mx