Mariana starts her day with a cup of coffee, “sweet and with milk,” she laughs. She enjoys it and uses the early morning silence to organize her thoughts and let them flow.

In the morning, she might run or pick up a book. Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children is on her table, usually followed by a text related to her field, the most recent being Trans* by Jack Halberstam.

Although she has been teaching certain subjects for around 20 years, the professor and researcher at the School of Humanities and Education at Tec de Monterrey reviews her classes because she believes it is important to keep the material fresh.

After studying International Relations and a Master’s in Social Sciences in Mexico, she earned a PhD in Human Geography from the School of Geography and the Environment at the University of Oxford.

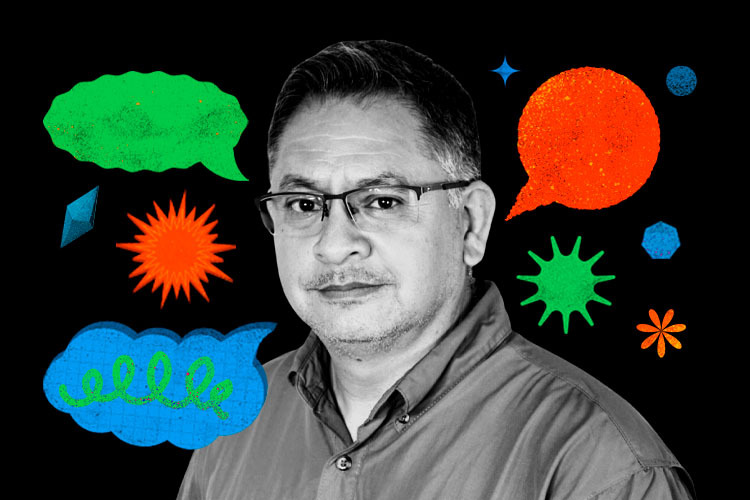

With flushed cheeks and carrying a backpack full of pins and badges, including the LGBTQI+ flag, she arrives at the interview with TecScience, greets us all, and takes a few seconds to catch her breath before beginning.

“I’m Mariana Gabarrot,” she starts with a smile, her face refreshed after applying thermal water. “And I don’t believe in labels,” she says in response to the first question, kicking off nearly two hours of questions, laughter, and honesty.

“I think we need to problematize labels constantly,” she says firmly but kindly. “Maybe I use them strategically. When I’m at Tec, I’m a professor… I don’t like being called ‘Miss’ at all,” she emphasizes. “But when I’m with my family, I can be a daughter or just Mariana, the same with my friends. Labels vary and flow; honestly, I don’t know who I am because being is a process.”

The author of The ABC of Gender tries not to hold many certainties about identity, emphasizing the need to constantly question who we are, where we are going, why we are here, and how we choose to inhabit the world.

“Who are you? Who am I? If we use categories to define ourselves, they have to be open, and we have to keep questioning them and why we decide to use them and when.”

Bodies and Migrations

This constant questioning and the intention to understand in depth the self with the physical body is partly what has defined her academic life, combining her training in this area with gender studies, migrations, feminism and how we understand everything in an interrelated way.

“I’m interested in knowing what moves us, what makes us seek these other ways of existing with the others, and what is that that unsettles us. To discuss what kind of society we want, what types of bodies enter social legitimacy, what bodies don’t,” she said.

Why did you focus on migration?

“My parents left Uruguay looking for a safer place. There was a military dictatorship and a lot of violence. They came to Mexico looking for a place to make a life. I arrived to Monterrey at six years old.”

Although Mariana’s experience arriving Mexico was relatively easy, she recognizes the precariousness of other migrants who, despite having the same dream as her parents, are violently and inevitably ignored. By being unable to give them an identity, a face, the dead migrants become just numbers, but when we talk about bodies, especially when we can see those bodies, the discourse changes.

“For me, having always studied these social phenomena of historically vulnerable people, it was always an enigma to think: why we accept this to happen? why we accept the deaths of migrants? why is there rejection of undocumented people. And that eventually led me to gender studies.”

Teaching, Justice, and Support Among Women

What interests you in research? What is that, what you aim to know?

“That’s a very good question, one I always ask myself. We have corseted knowledge production from social sciences and humanities into indicators and academic articles.

For me, researching and approaching reality doesn’t necessarily go through that. I believe that knowledge, and in this, I strongly appeal to queer theory, is made from experience, from below; I am interested in many topics, but I focus on what we live. It seems it is difficult to do science and ask about the abstract. In the case of women in Mexico, where 11 are killed a day, how can I sit down to analyze numbers and not go and listen to the discourses and stories of those on the front lines?

When I study gender violence, I’m not studying data nor people in the abstract; I’m accompanying survivors, whether they are migrant women I visit, students who come to my office, or friends I have coffee with.”

A Close Professor

A constant theme Mariana mentions in her life, work, and different roles is the impact the women around her have on her, particularly when we talk about her students and friends, who have supported and driven her toward gender studies through their stories and experiences.

Ten years ago, Mariana started, along with her colleagues and students, the Week of Feminisms, offering three open classes to discuss these topics; this project boosted her involvement in developing and monitoring the protocol to prevent and address gender violence at Tec de Monterrey, as well as her book The ABC of Gender.

What role have the women close to you played in your development as a researcher, professor, and person?

When we started with gender topics during the Week of Feminisms, I got directly involved in opening dialogues between my students and raising awareness about the importance of understanding them. That was when I realized that being a professor distant from students’ problems was unsustainable. Working on these gender topics, my study subjects were my students, colleagues, friends, and myself.

By accompanying them, I realized the importance of my students and colleagues, knowing they could have someone in me who would listen without judging.

A rainbow flag with a yellow smiling face decorates her office window in the Department of Humanistic Studies at the Monterrey campus. Mariana explains how that simple, happy face represents something similar to the pins on her backpack.

“The idea for the sticker came from a colleague, Ana María Alvarado, who said we should put a sign in the office so students would know they could talk to us even if they didn’t have a class with us. She printed the stickers, and we put them up.”

A diversity flag, a purple scarf representing the feminist protest, and a sticker with the phrase “I believe you” on her computer are some of Mariana’s silent invitations, alongside the vocal ones about her willingness and openness to be a companion who never offers advice but does the most important thing: listen.

“My friends do the same with me. We listen to each other, they listen to me, they encourage me and give me reality checks,” she says, laughing, “for me, a friend is not someone who lectures you, because lecturing someone always comes from a position of power. A friend keeps you company and may point out when seeing an issue that concerns them. That’s what I’ve sought to be.”

A Path of Self-Reflection and Constant Change

How would you like us to perceive you after reading this interview?

“I’d like you to see in me other possibilities for constructing knowledge beyond the orthodoxy of scientific knowledge.

I don’t consider myself part of that rigid knowledge, but I’ve been dedicated to academia for 28 years, and my experience has guided both my practice and my interaction with others. I want to show that just as there are many ways to inhabit the world, there are many ways to exist in academia.”

Her voice softens once the cameras stop recording. Talking with Mariana is a warm and intimate experience, where honesty leads the conversation, not only in her answers but even in her feelings.

“I don’t like the spotlight. Posing and changing poses, looking here or there. I have always appealed to the collective, but I also recognize that when my students, colleagues, and friends see me, they don’t just see me. They see other ways of existing,” she expressed before looking back and laughing, “I think I didn’t answer the question, but that’s how I am.”

That’s how Mariana is. After a conversation that, from the start, required us to reformulate questions and constantly challenged us as well, she says goodbye, walking until she blends into the wave of students leaving class. The last thing we see is her backpack full of pins as she heads back to her office since she “shuts the shop at eight o’clock at night”.