In recent years, Latin American governments have increasingly turned to artificial intelligence (AI) to automate public administration processes, covering areas such as health, education, security, justice, and social programs [1].

This reflects a global trend toward leveraging technology for more efficient public service delivery.

However, the region’s technological dependency and the influence of foreign tech corporations often skew AI policies toward external corporate interests rather than local priorities.

Weak regulatory frameworks, insufficient risk assessments, and limited oversight exacerbate these challenges, compounded by infrastructural and technical limitations.

In politically and socially fragile contexts marked by inequality and authoritarianism, AI systems risk being misused for social control, raising concerns about their ethical and equitable implementation.

Algorithmic Governance: What It Is

State automation reflects the concept of algorithmic governmentality [2], defined as a mode of “governing the social world through the algorithmic processing of vast datasets” [3].

This “political rationality” reconfigures governance, where algorithms begin to supplant traditional mechanisms like politics, legal frameworks, or social norms [3].

In Latin America, this rationality is shaped by narratives emphasizing security, development, and innovation, often influenced by the economic interests of tech corporations and the geopolitical agendas of nations that dominate these technologies.

Causing AI systems to transcend their role as mere technological tools, and becoming agents of deeper systemic change.

Automation reshapes power dynamics, blending soft power (persuasion) with underlying hard power (coercion).

AI systems’ versatility allows them to serve as instruments of hard power—such as automated weapons, border surveillance, or policing—while also functioning as soft power tools, subtly enabling social control through their integration into public decision-making processes.

Regulatory frameworks for AI

Some Latin American governments have created permissive regulatory environments prioritizing corporate interests over their duty to uphold human rights and protect the public good.

Indeed AI policies in the region often lack a cohesive, sovereign vision and long-term strategies for AI systems development and deployment.

Robust regulatory frameworks are needed to encompass technical, legal, and institutional protocols [4]. These should include mechanisms for algorithmic audits, accountability, remediation of harm caused by algorithms [5], and guarantees of non-repetition.

Without effective checks and balances, the automation of public administration risks undermining human rights and democracy, exacerbating social inequalities. Failure to adequately implement and monitor these systems could further marginalize vulnerable populations [6].

Moreover, the opacity surrounding the procurement and operation of these technologies can conceal corruption and facilitate their misuse for purposes unrelated to public welfare, undermining trust and accountability in governance.

Civil society organizations in the region, such as Derechos Digitales in Chile, Fundación Karisma in Colombia, and Coding Rights in Brazil, have documented the implementation of these systems across various countries. Below are two case studies from Brazil [7] and Chile [8].

Lack of transparency in Brazil

In Brazil, the Ministry of Economy and Microsoft have partnered to optimize job allocation through the National Employment System (SINE). However, this initiative has drawn criticism for its lack of transparency and potential for discrimination.

A key concern is the absence of explicit informed consent for processing personal data. While Brazilian law generally requires such consent, exceptions for public policy purposes permit Microsoft to access and process data without users’ direct approval.

The system also lacks comprehensive audit mechanisms to detect and address potential biases. Although Brazil’s legal framework provides for compensation in cases of harm caused by errors in automated systems, the absence of rigorous audits hinders early identification and correction of these issues.

Furthermore, citizens didn’t get involved with the system’s design and implementation raising additional concerns about accountability and transparency undermining public trust in the initiative.

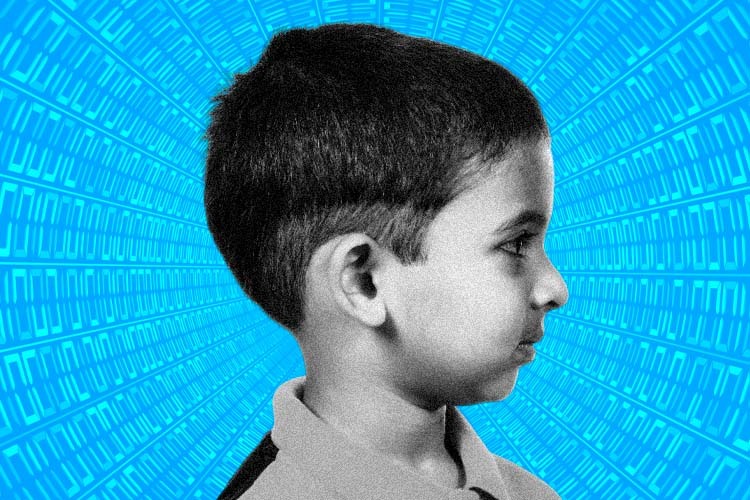

Alert to children’s rights

Chile’s Alerta Niñez, a pilot project designed to predict the risk of rights violations against children and adolescents, faces significant challenges.

While guardians provide consent for data processing, the consent form lacks clarity regarding how the system works, particularly its ability to predict risks.

The system’s dependence on administrative data sources raises concerns about perpetuating existing biases. Since these sources predominantly reflect individuals already engaged with public policy interventions, the system risks disproportionately overestimating risks for disadvantaged populations while underestimating them for more privileged groups.

Additionally, limited transparency in evaluation and audit processes undermines public scrutiny and accountability. Although an algorithmic audit has been announced, the criteria and responsible entity remain undisclosed.

Such automation of public services poses heightened risks for marginalized communities. Delegating decision-making to algorithmic systems can lead to rights violations, reinforce systemic barriers to justice, dilute state accountability, and restrict access to remedies for harm.

Algorithmic Risks

Key risks in the Latin American region include an overreliance on private sector actors, such as Microsoft, for these system’s development and implementation without sufficient evaluation or audit processes. This raises significant concerns about transparency, accountability, and potential conflicts of interest.

The lack of robust regulatory frameworks and independent oversight institutions across the region further exacerbates these issues. Governance mechanisms are urgent to safeguard fundamental rights from the unchecked expansion of automated decision-making systems in Latin America.

As AI systems become increasingly integrated into state functions—fostering public participation and raising awareness of their societal impact—is critical.

Involving citizens in technology’s design, implementation, and evaluation can strengthen transparency, accountability, and trust in public institutions.

Given the challenges associated with state automation in Latin America, deploying AI systems must be guided by stringent regulatory frameworks that prioritize human rights, uphold democratic values, and advance social justice.

Original article:

Ricaurte, P., Gómez-Cruz, E., & Siles, I. (2024). Algorithmic governmentality in Latin America: Sociotechnical imaginaries, neocolonial soft power, and authoritarianism. Big Data & Society, 11(1).

References

- Varon, J. y Peña, P. (2021). Notmy.ai. Proyectos de IA del sector público en América Latina.

- Rouvroy, A. y Berns, T. (2013). Algorithmic governmentality and prospects of emancipation. Réseaux 177(1): 163–196.

- Rouvroy, A. (2020). Algorithmic governmentality and the death of politics. Green European Journal 27: 1–5.

- Hernández, L., Canales, M., & de Souza, M. (2022). Inteligencia Artificial y participación en América Latina: Las estrategias nacionales de IA. Chile: Derechos Digitales.

- Davis, J. L., Williams, A., & Yang, M. W. (2021). Algorithmic reparation. Big Data & Society, 8(2), 1–12.

- Busaniche, B. (2020). Negligencia, La Inminente Amenaza a Nuestra Privacidad.

- Bruno, F., Cardoso, P. y Faltay, P. (2021). Brasil. Sistema Nacional de Empleo. Derechos Digitales.

- Valderrama, Matías. (2021) Chile. Sistema Alerta Niñez. Derechos Digitales.

- Fundación Karisma (2024). Contribuciones al Relator Especial sobre la extrema pobreza y los derechos humanos: El Sisbén y la exclusión por default.

- Ministério do Trabalho e Emprego. (s/f). Sistema Nacional de Emprego – SINE.

- Velasco, P. y Venturini, J. (2021). Decisiones automatizadas en la función pública en América Latina Una aproximación comparada a su aplicación en Brasil, Chile, Colombia y Uruguay. Chile: Derechos Digitales

Author

Paola Ricaurte Quijano. Senior researcher at the School of Humanities and Education at Tecnológico de Monterrey, affiliated researcher at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, and co-founder of the Tierra Común network. She coordinates the Latin America and the Caribbean node of the Feminist Research Network on Artificial Intelligence. She is an expert in the Global AI Alliance, a member of the AI Ethics Experts Without Borders network, and part of the Women4Ethical AI platform of UNESCO.