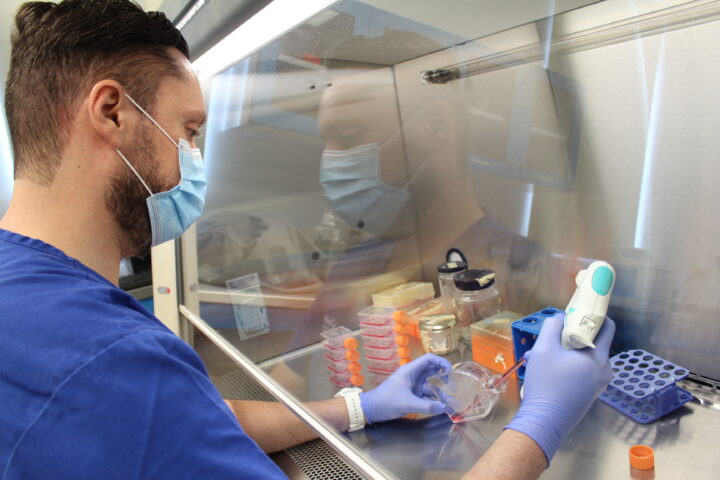

In his lab at Zambrano Hellion Hospital, surrounded by meticulously disordered stacks of papers and books, Gerardo García-Rivas talks about how his lab has grown over the past 17 years. He wears a bluish three-piece suit without a tie, and as he speaks, he’s constantly moving. Gazing at his lab through his burgundy glasses, he also shares his love for cooking and dining, engaging conversations, and music.

His career is a testament to the importance of mentorship in science. From his early days at the National Institute of Cardiology to his current position as Director of Translational Research at TecSalud and leader of a unit at the Tec de Monterrey’s Institute for Obesity Research, each stage of his career has been marked by mentors who have shaped his vision.

Recently awarded the Maximiliano Ruiz Castañeda Prize from the National Academy of Medicine, his work redefines the relevant questions in cardiovascular disease. The award-winning study tackles one of the most pressing challenges in Mexican healthcare today: the emergence of a new type of cardiovascular disease.

This research, which took four years to complete, examines how two demographic trends—an aging population and rising obesity rates—dramatically change the landscape. The most significant finding is the identification of a new pattern of cardiovascular disease that primarily affects women with obesity and diabetes, quite different from the traditional profile of the cardiac patient (typically male smokers with hypertension).

This distinction is crucial because it explains why conventional treatments often fall short in these new cases, paving the way for the search for more effective therapies for this growing patient population.

When you were starting your career, did you ever imagine reaching the elite of researchers?

I’m very, very active. I don’t stop, and when I was young, it wasn’t in my personality to reflect on what I expected from the future. I was more interested in the day-to-day, in getting a lab up and running, in making the experiments work, and in ensuring the questions we took on were relevant enough to interest funding agencies and allow us to keep moving forward. My vision has been to generate knowledge and make contributions; from there, things have fallen into place.

Being so young, what drew you to this work?

Since I was a child, I realized I was interested in things relating to life, microscopes, and the germination of seeds. My father is a doctor, and my mother was very involved in the biological field, so these topics were constantly brought up at home. We naturally gravitated towards medical careers: my brother is a psychiatrist, and my sister is a dentist.

At 17, I was already in a lab studying heart metabolism problems, and this caused me to zero in on my career very early on. I graduated with my doctorate at 24 and, at that age, was already a postdoctoral researcher in the United States. At 28, I was hired by Tec as a professor.

Did you feel ready at 28?

Absolutely not. What I had was a lot of drive. A couple of years after I joined Tec, Guillermo Torre came on board as Rector of TecSalud. Since he specialized in heart failure physiology, I was lucky that we could have many discussions on a very horizontal level. We’ve always worked very collaboratively, and in those early years when I felt very uncertain about the future, Guillermo was a guiding light that allowed me to see a path forward.

Beyond the Lab

His days are split between his two roles at Tec de Monterrey. As Director of Translational Research at TecSalud, he evaluates and guides projects that can directly impact patient health, analyzing everything from the viability of new medical devices to the potential of promising molecules, always considering regulatory and market aspects.

At the same time, he leads the Experimental Medicine unit at the Institute for Obesity Research, where he coordinates a team dedicated to developing new drugs and therapeutic targets.

Despite these administrative responsibilities, he is committed to training new researchers.

What does that weekly time you dedicate to your students mean to you?

A lab’s reputation depends on the quality of the results, the strength of the work, and the questions asked. On Wednesdays, I set aside at least four hours to review the results, from the undergraduate student to the postdoctoral researcher about to finish a manuscript.

It’s also a very educational time because the younger students see how the seniors present and recognize how the more experienced researchers critique. They take it on board for their following presentations.

Being holed up for three or four hours discussing multiple people’s results can be tiring, but it’s how I ensure the quality of our research group’s work.

And outside of all this, what about your personal life?

In the lab, I’m very demanding and highly disciplined. Outside of it, I’m entirely bohemian, and I enjoy socializing and throwing get-togethers. I dedicate a lot of time to cooking: I love cooking and eating, wine, conversation, and music.

I like my students to get to know me in that social setting; sometimes, I might invite some professors or students over on a Saturday to enjoy a meal or a wine tasting, where there’s always a laugh or an anecdote. They know that their mental and physical health, their relationship with their family, and their emotional state are priorities.

The Power of Mentorship

In the development of science, mentors play a fundamental role in shaping methodological rigor and the vision and scope of research. Throughout his career, mentors have been key in shaping García-Rivas’s research style, which combines scientific excellence with clinical relevance.

You mentioned Guillermo Torre; what other mentors have been important in your career, and what lessons did they impart?

At the National Institute of Cardiology, Cecilia Zazueta and Edmundo Chávez Cosío had an extremely rigorous research group regarding data, review, expectations, and experimental design. They taught me that research can be stunning if you dedicate yourself to solving fundamental questions without looking for an immediate commercial application. That was the cornerstone: deep, rigorous work and respect for the implications of the findings.

The second was Guillermo Torre, who made my fundamental questions turn into aspects that were indeed a concern for the physician. Sitting in a lab next to a clinician trying to solve a patient’s problem changes your perspective as a researcher. Guillermo is someone who has taught me to think big.

Dr. Marco Rito has been essential in the last part of my training. I was lucky enough to start collaborating with him at the Institute for Obesity Research, and with him, I learned about administrative processes, time management, I learned to prioritize, to be executive, to lead a team. With Marco, it’s been about seeing that we can achieve everything if we keep our feet on the ground and working at it.

What would you tell a young researcher about the importance of having mentors?

That is the best way to learn. If you don’t see how researchers conduct themselves with discipline, resilience, and the search for resources, the training will be different. I was lucky enough to experience it, and not only in the professional aspect, and I’ve picked up something from each of my mentors.

I consider it fundamental that mentorship goes beyond academics, and that’s something they don’t tell you much either. A good researcher also has to be a good person.

Research can be such a strong passion that it can run over many other things, but finding balance is also something you learn. For me, it’s been fundamental to have mentors who are willing to share not only their knowledge but also their lives. Being on the lookout for a mentor who aligns with your values, with your way of seeing life is very important to me.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx