If the United States stopped changing the clocks twice a year, there would likely be a drop in obesity rates and the number of strokes nationwide, according to a new study conducted by Stanford University researchers.

The study estimates that adopting permanent standard time could prevent roughly 300,000 strokes annually and reduce the number of people with obesity by 2.6 million, compared to the current biannual time changes. Permanent daylight saving time would also bring health benefits, though to a lesser extent.

In Mexico, the practice of switching to daylight saving time was abolished in October 2022. However, some border states and municipalities still adjust their clocks in March and November to align with U.S. economic activities.

Published in the scientific journal PNAS, the study compared the potential impact of three different time arrangements—permanent standard time, permanent daylight saving time, and biannual clock changes—on circadian rhythms and public health.

A Closer Look at the Study

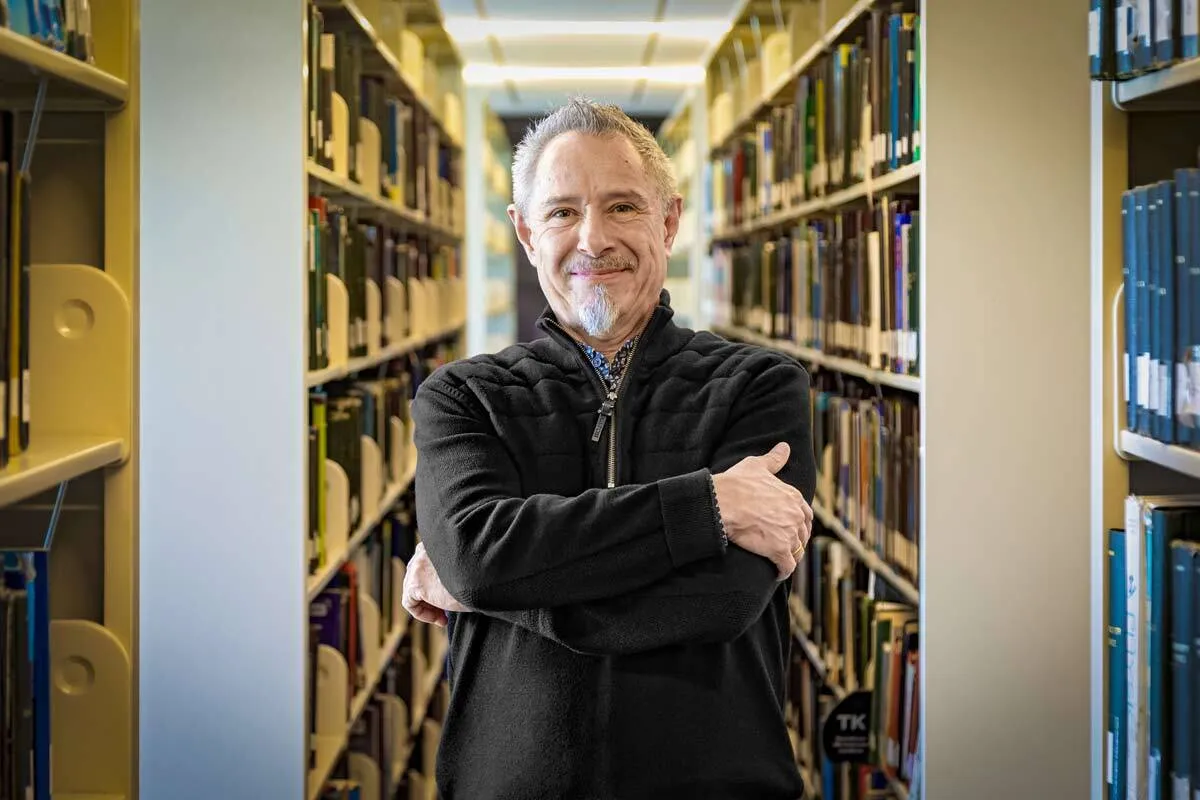

Juan Antonio Madrid Pérez, professor of physiology and director of the Chronobiology Laboratory at the University of Murcia, described the research as “pioneering” for quantifying the chronic effects of time policies on health, something that, until now, has been scarcely studied.

“Its conclusions support the idea of abandoning seasonal time changes and opting for permanent standard time (closest to solar time) as the healthiest option for the majority of the population,” Madrid Pérez said.

He added that although the model assumes ideal light conditions and does not account for all real-world factors, such as irregular sleep schedules or time spent outdoors, it provides a solid scientific basis for the ongoing debate about time policy reform.

Every spring, Americans set their clocks forward by one hour, and in the fall, they set them back to standard time.

Previous studies have linked the loss of one hour of sleep on the second Sunday in March to a spike in heart attacks and even an increase in traffic accidents in the days immediately following the change. However, until now, the broader biomedical impact of sticking with a single year-round time policy had not been fully understood.

“These health effects depend greatly on latitude and a community’s longitudinal position within a time zone,” the study noted. “It will be crucial to consider these data in ongoing debates surrounding time policies.”

Researchers also found that both a person’s chronotype—whether they are naturally more of a morning or night person—and their geographic location play a key role in how these shifts affect health.

Benefits Back the End of Clock Changes

The study examined these patterns alongside U.S. county-level health data. Under idealized light exposure conditions and after controlling for health and socioeconomic factors, researchers found:

- Permanent standard time would decrease obesity prevalence by 0.78% and stroke prevalence by 0.09% compared to the current policy.

- Permanent daylight saving time would also reduce obesity (0.51%) and stroke rates (0.07%), though to a lesser degree.

“Our data, which reflect the impact of time policies on circadian strain and related health benefits, support the elimination of the biannual clock change,” the study concluded.

Methodology and Limitations

The research relied on previously validated mathematical models of the circadian system (a modified Jewett–Forger–Kronauer model) and official datasets containing socioeconomic and health indicators.

However, María Ángeles Bonmatí, lead researcher at the Murcia Institute for Biomedical Research and professor in the Department of Human Anatomy and Psychobiology at the University of Murcia, noted some limitations.

Only intermediate chronotypes were included, meaning the results could differ if individuals with strong morning or evening tendencies were considered.

“In addition, the analysis focuses solely on the impact of time policy on the circadian system and not on its effects on other aspects of health, the economy or social behaviour,” Bonmatí said.

Both Bonmatí and the study’s authors emphasize that this is a theoretical modeling study, not one based on experimental trials or long-term real-world follow-up.

“Nevertheless, the study adds value by systematically comparing three scenarios: the current biannual change and permanent standard and supposed energy-saving schedules, and predicts chronic beneficial effects from maintaining a fixed schedule,” Bonmatí explained.

In conclusion, she highlighted that while the research has its limitations, it is a solid, peer-reviewed study which reinforces the evidence that the biannual change is the least healthy option.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx