In Venezuela, they’re known as “barrios de rancho.” In Colombia, “urbanizaciones pirata” or simply, neighborhoods. In Brazil, they’re favelas. Here in Mexico, they’re known as irregular settlements. Although the name changes, the essence of these structures stays the same: urban spaces on the margins of institutional formality, where millions of people build their homes and their lives.

According to the United Nations (UN), more than 1.2 million people worldwide inhabit these spaces: homes without water, electricity, or gas, at least not formally. A team of researchers from Tecnológico de Monterrey has undertaken a longitudinal study to understand and document the world of urban informality and self-produced housing.

Urban informality exists in various forms, from informal commerce like taco stands that appear in many corners of Mexico to unregulated transportation. However, Elfide Mariela Rivas Gómez, Natalia García Cervantes, and Lucía Elizondo Giménez from the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) at Tecnológico de Monterrey are focusing their research specifically on settlements and self-produced housing in urban contexts like Monterrey.

New Informal Settlements Are Not Only On The Periphery

Self-production refers to housing where inhabitants assume responsibility for its development, either by physically building it themselves (self-construction) or organizing the production process, including hiring workers and obtaining materials. This differs from formal housing markets and government-sponsored projects that don’t sanction self-produced housing but also don’t shut them down.

One of the most surprising findings of the research is the scale of this phenomenon. Elizondo points out that more than 60% of housing in Mexico has been self-produced.

This represents a significant majority of the population, despite most urban studies focusing on formal social housing programs like Infonavit. This knowledge gap is the main objective of their longitudinal study.

The researchers were surprised to discover that, contrary to expectations, new informal settlements are not necessarily pushed to the periphery. They are within the municipality of Monterrey, in the northern part of the city. “There is a deep poverty that is ignored—almost like a collective delusion for those living in Nuevo León,” Rivas said.

The invisibility extends to official recognition as there is no national census inventory of irregular settlements in the country, Rivas explains. “These citizens exist for the National Electoral Institute to vote, but for public policies related to improvements—equipment for education, recreation, health, efficient public transportation, street paving, sidewalks, 24-hour water services, electrification—they don’t exist.”

From Informality To Regularization And Ways To Inhabit

What defines a settlement as informal mainly relates to land tenure. These communities develop on land that is privately owned, ejidal lands, or land with complex legal status.

For regularization to occur, settlements must meet specific requirements established by Fomerrey, the state institution responsible for land formalization. These include lot dimensions (typically 7×15 meters), street widths of 8-10 meters, and other urban planning parameters.

Over time, newer informal settlements are established from the beginning conforming to these formalization requirements. Elizondo observes that residents are “making Fomerrey’s job easier by designing settlements that already meet their standards.”

However, formalization is not a linear process. Some settlements established since 1994 still lack basic services due to unresolved land tenure issues. Until regularization occurs, these communities cannot legally access essential services officially.

During their visits to these homes, the researchers noted how residents develop ingenious solutions to meet basic needs. For electricity, they create informal connections, although this involves risks of fires and outages.

Water is distributed through improvised hose networks in a system locals call “bomberos,” where community members manage water distribution. Sewerage is typically managed through septic tanks, which represent health hazards during rainy seasons. The housing itself is built without technical assistance, often by construction workers who build based on their experience without formal engineering knowledge.

These conditions creates vulnerability, particularly in areas with slopes or unstable soil.

Women, Their Role And Pride In Their Neighborhood

One of the most significant findings relates to gender dynamics. “The role of women both in housing development and settlement development stands out,” said Rivas.

Many of the tours and interviews they conducted with residents were with women who are in charge of daily life. Rivas explained how many of the women often lead the fight for services, formalization processes, and community organization while simultaneously managing childcare and household responsibilities.

Despite challenging conditions, the researchers observed strong collective bonds and resilience. “It’s a process that happens in community. They weave community while forming their own houses and settlements,” says Elizondo.

These support networks are crucial for survival and development. The researchers also noticed a sense of pride among residents, particularly in women. “They are proud of where they are, because they know they have solved by themselves something the government should have done for them,” observes Elizondo. “It’s a right, just like health and education.”

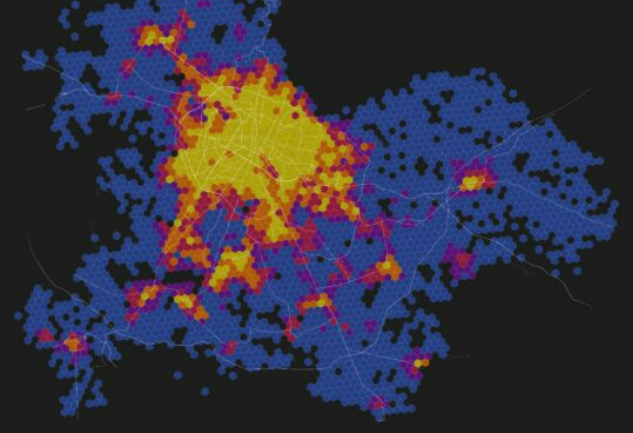

The research team has adopted a longitudinal approach, planning to study these communities for at least ten years. Their work spans multiple fronts, including theoretical articles on liminality in urban informality, comparative studies with Colombia, and artificial intelligence applications to map informal settlements.

The researchers are developing a digital platform called “To Inhabit is to Resist” to connect communities and make their stories visible.

“We’ve realized that, while there’s an impressive effort by these women, they are limited to their own neighborhood,” said Rivas. The platform aims to help communities recognize each other’s efforts and potentially organize collectively.

The Importance of Semantics

They also seek to influence public policies through evidence-based recommendations, emphasizing that universities must engage with social realities. A particular challenge they face is the semantic question: terms like “irregular,” “illegal,” or “squatter” have negative connotations.

The team promotes the use of terms like “self-produced” to recognize the positive contribution these communities make to city construction in the face of state non-response.

Through their comprehensive and long-term research approach, these scientists are not only documenting urban self-production but working to transform how we understand and address self-produced housing—recognizing it as a significant mode of city construction that demands visibility and support rather than marginalization.

As Rivas notes, after seeing the resilience of these communities and their ability to smile despite precarious conditions for decades, “That speaks to you of resilience, another term that I think is crucial to highlight about these families, these women, and these people.”

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx