In Mexico City’s Condesa neighborhood, those who were born there or have lived there for generations have seen a decline in their quality of life. New tenants are replacing their friends and family, noise and pollution are increasing, and, due to the expansion of restaurants onto the sidewalks, they have less and less space to walk. At the same time, more digital nomads from the Global North are moving there.

In academia, this process is called transnational gentrification: an urban transformation in which the arrival of foreign populations—with greater purchasing power—causes an increase in the cost of living, displacing local residents and changing the identity of the place.

“Before the pandemic, it was very linked to expats aged 50 and older who were looking for quiet places like San Miguel de Allende to retire,” says David Navarrete, a research professor at the University of Guanajuato.

Following the pandemic and the expansion of remote work, the profile of foreigners arriving, as well as their destination, has changed: they are now young, working-age people living in large cities in countries in the Global South.

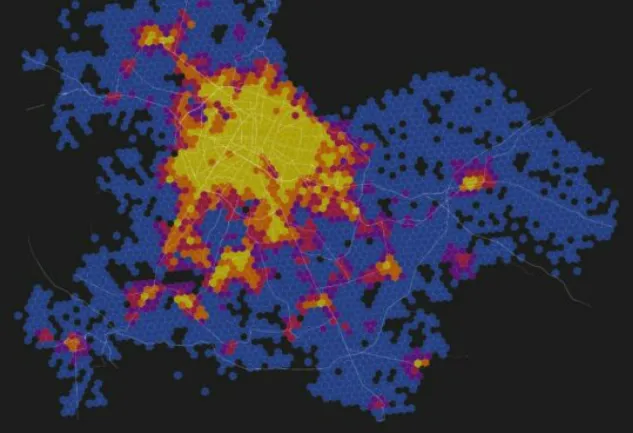

In a recent study, Navarrete, Ryan Whitney and Aleksandra Krstikj, research professors at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) of the Monterrey Institute of Technology, analyzed this phenomenon in central Mexico City.

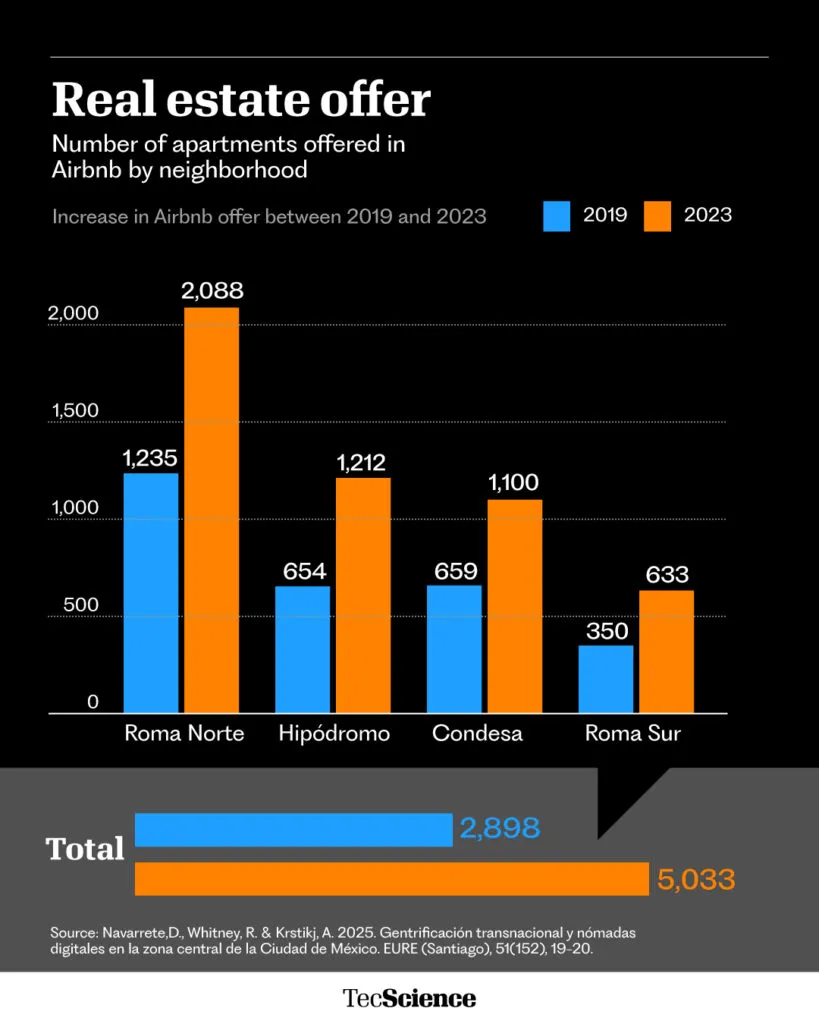

“We studied the Hipódromo, Condesa, Roma Norte, and Roma Sur neighborhoods because we think they offer what digital nomads typically want,” says Krstikj.

The New Wave of Transnational Gentrification

Gentrification is not new. It was first described in 1964, and since then, the term has evolved and expanded.

We know that it is driven by the State and capital, which through investments, tax incentives, renovation programs, and certain laws, encourages the arrival of wealthier people, whether from within their own country or from abroad.

The consequences of transnational gentrification include rising housing and service costs, dollarization of the economy, specialization in tourism, appropriation of public space for consumer activities, and the direct or indirect displacement of the local population with lower purchasing power.

Direct displacement occurs when landlords end leases or raise rents and people can’t afford the prices. Indirect displacement occurs when the cost of living becomes prohibitive for low-income families.

A distinctive feature of gentrification driven by foreign digital nomads is its rapid expansion, reaching enormous proportions in less than five years. Recently, the perception of its negative impact on the national population has grown too.

“I think there’s more civic organization in Mexico City, so it hasn’t been that long before someone spoke up and said, ‘Something’s happening here, and it’s a problem,'” Navarrete says.

This is reflected in anti-gentrification protests held in the city since July.

Greater Supply of Airbnbs and More Expensive Rents

In the study, researchers used quantitative and qualitative data to analyze the impact of foreign digital nomads in the central Mexico City area.

One of its main findings is that in 2019—before the pandemic—there were 2,898 homes for rent through Airbnb in the Hipódromo, Condesa, Roma Norte, and Roma Sur neighborhoods; by 2023, the number had risen to 5,033, representing a 74% increase.

With this growth, there have been documented cases of evictions of entire buildings that were renovated and transformed into exclusive rental spaces for this platform.

The area has also seen a commercial transformation with the creation of gourmet restaurants and cafes, bars, coworking spaces, pet shops, and designer boutiques, businesses that are increasingly clustering around these neighborhoods.

“This could be linked to the digital nomad lifestyle,” says Krstikj.

Similarly, since 2020, the number of businesses with a foreign name increased from 16.3% to 32.5% in 2022.

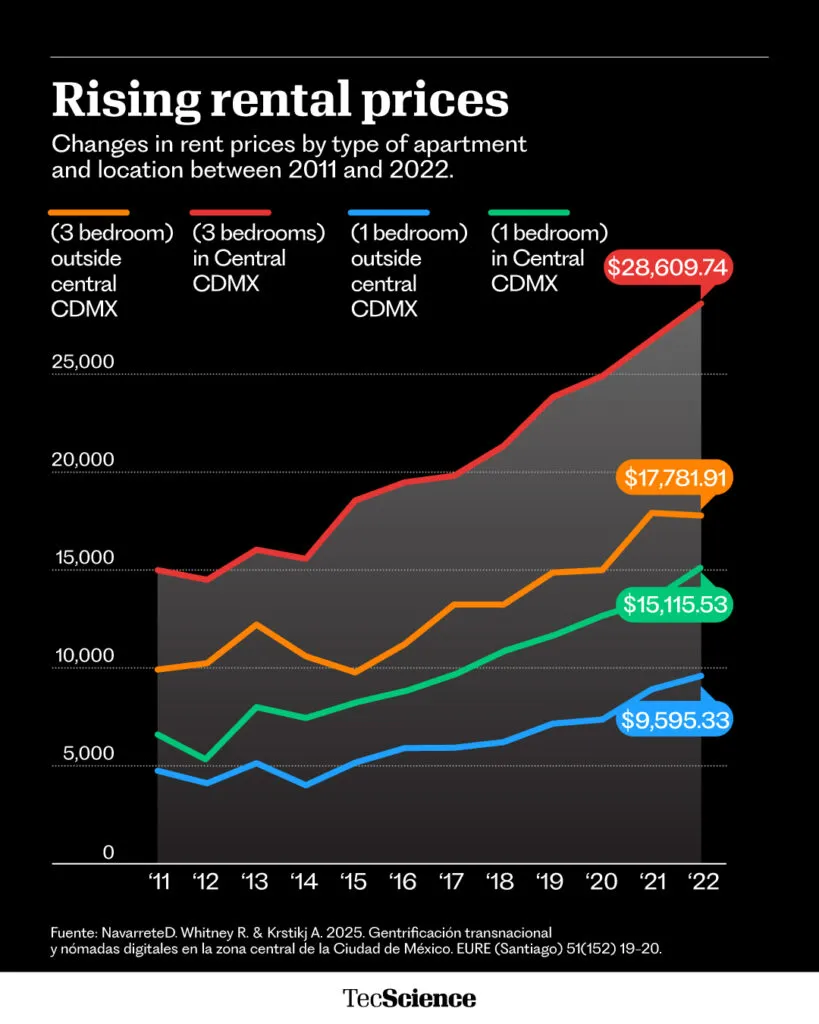

Additionally, rents increased 30% and 15% for one-bedroom and three-bedroom apartments.

At the same time, the cost of certain products has skyrocketed: cheese prices rose 48%, a bottle of wine 64%, and bottled water 44%, to name a few.

Does this Affect the Local Population?

To analyze whether these changes have an impact on the displacement and exclusion of locals, they reviewed data from the National Council for the Evaluation of Development Policy (Coneval) and found a coincidence in time and space:

between 2015 and 2020, the percentage of residents in these neighborhoods who reported a lack of decent housing increased from 2.6% to 3.6%.

During that same period, poverty and extreme poverty increased significantly, just after Airbnb became popular.

In two community meetings to address gentrification among resident groups in La Condesa, Hipódromo, and Juárez, participants expressed concern about the area’s transformation after the pandemic.

They reported a decline in their quality of life and less pedestrian mobility for older adults, those in wheelchairs, or those with walkers.

“While it doesn’t establish causality—the fact that prices are rising but the local community is poorer—is a very clear indicator that these changes aren’t benefiting them,” says Krstikj.

For foreigners from the Global North, living in a city like Mexico City is ideal for its connectivity, culture, and entertainment. Although rent has become more expensive for its residents, it is still between 68% and 78% cheaper than in cities like New York or Los Angeles.

“This is a result of long-standing structural inequalities between the Global North and South,” says Navarrete.

Is Transnational Gentrification to Blame for how Expensive Everything is?

While this might lead us to conclude that foreigners are responsible for the high cost of living in Mexico City, this is not the case.

“At first, gentrification was national and then it moved to a transnational scale but because globalization, capitalism, neoliberalism, and mobility allowed it,” Navarrete says.

Gentrification benefits businesses, real estate developers, and people who have the capital to invest and profit from housing, who are often Mexicans.

Transnational gentrification occurs globally, but it’s worth analyzing why the narrative changes when migration occurs from the Global North to the Global South.

“Those who move from the South are stigmatized and hated, but those who come from the North arrive in a privileged position because of the currency exchange,” says the researcher. “They aren’t called migrants, but expats.”

Navarrete’s hypothesis is that the current reaction to gentrification in Mexico stems from a combination of factors that coincide with the xenophobic and racist rhetoric of the Donald Trump administration toward Latin Americans.

“There’s still a need to create an other, an enemy, an invader,” Navarrete emphasizes. “For all this, the gringo is used as a scapegoat.”

For the expert, this could be distracting citizens from demanding accountability from those who are truly responsible: the government and the companies that have allowed it.

Insufficient Measures Against Gentrification

In response to the debate and protests against gentrification, the Mexican government has announced measures such as regulating Airbnb and banning rent that exceeds the annual inflation.

But Navarrete remains skeptical: “I don’t want to be pessimistic, but I think they won’t be sufficient or effective; I feel they’re more media-driven,” he says.

According to him, the law regulating Airbnb is too lax, and the law that restricts rent increases already existed, but has never been enforced because the State lacks the capacity to ensure compliance.

“The effect of these regulations will be very small as long as the current global capitalist economic model doesn’t change,” says Navarrete. “But no government has that power.”

What could help Mexico is to structurally change housing policy, economic policy to improve wages, seek a balance between local communities and digital nomads, and restrict real estate projects that seek to profit from housing, according to researchers.

“The State can begin mass-producing housing,” Navarrete suggests. “But as long as the structural elements of the right to housing and the city remain unresolved, the impact of these measures will be minimal.”

Were you interested in this story? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more: marianaleonm@tec.mx