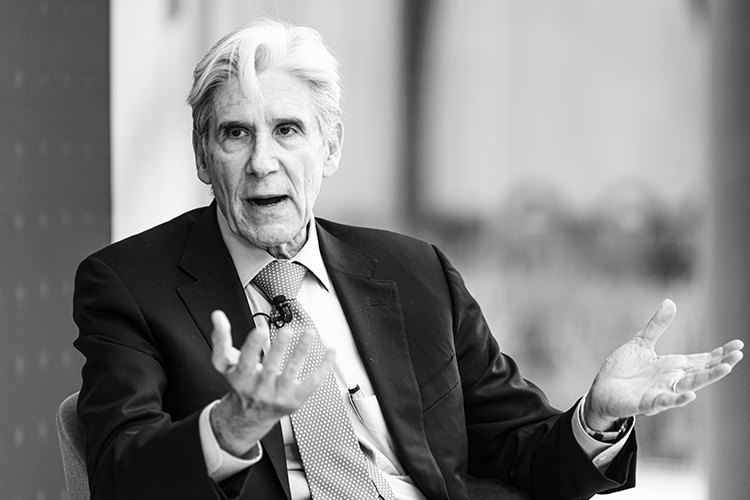

Julio Frenk Mora is a Mexican surgeon who served as the Minister of Health for six years (from 2000 – 2006) and oversaw the beginning of the Seguro Popular, a past government initiative to provide free or subsidized health insurance coverage to those uninsured or unemployed.

As a public official, he focused much of his knowledge on generating a response plan for health emergencies and pandemics in the country.

In an interview with TecScience, Frenk Mora reflects on the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, why it meant a loss in life expectancy for Mexico, and what steps we must take to avoid future pandemics and to have a safer world.

In October 2021, a study published by the journal Canadian Studies in Population reported that during the pandemic, life expectancy in México fell by at least 2.5 and 3.6 years for women and men, respectively.

Life expectancy

Why did the pandemic result in the loss of life expectancy in Mexico?

Well, it’s the effect of having excess deaths. In other words, life expectancy is a measure of mortality and we had one of the highest levels of excess deaths in the world, which now translates into a setback.

If we look not at the number of years that were lost in life expectancy, we went back 30 years. In 2021, we are having the life expectancy we had in Mexico in 1992. That means that between 2019 and 2022, in just three years, we lost 30 years of progress we had made.

We hadn’t had a general decline in life expectancy in Mexico for a century, the first time since the end of the armed phase of the Mexican Revolution.

There is something very wrong with our healthcare system… I don’t think there’s more dramatic proof of that.

Which steps can we take to strengthen Mexico’s healthcare system?

Well, the first thing we have to do is recover the capacity that was lost. Mexico had developed a response plan for pandemics. That plan, for example, was activated in 2009 with the AH1N1 pandemic. The country had a completely different response to the one we had with Covid-19. I believe it was a better response, government officials acted vigorously, there was a plan, and it was activated.

I had to prepare that plan when I was Minister of Health, even though the pandemic occurred in the next administration. It was created during a different government, but when the time came the plan was ready and it was followed. This was lost in this pandemic. Part of that plan was to have a strategic stock of many things, for example, protective equipment, such as face masks, antiviral drugs, and other supplies. That reserve must be restored. People who lived through the AH1N1 pandemic will remember that the day after the pandemic was declared, people were already wearing masks. This time, months passed before people could access them because there was a shortage.

The second thing is that, in Mexico, important increases to the budgets of the Ministry of Health have been achieved thanks to the Seguro Popular. In fact, that budget had quadrupled, adjusting for inflation, between 2000 and 2015. This has been lost; budgets have been falling since 2015 and in the current government they have practically been frozen. So, if we don’t invest more in health, we won’t be able to see improvements. And it isn’t only a matter of spending more money on health, but doing it efficiently, with transparency and accountability.

At this particular moment, I believe that one of the most concrete things we must do is achieve better coordination between our public health structure, epidemiological surveillance, disease control, and patient care infrastructure. They have to be better coordinated. To sum up, it’s all about recovering capacity and investing more.

Coexisting with the disease

What’s your view on the future of the pandemic, what will happen with Covid-19?

There’s always uncertainty in a pandemic because it represents a new organism, typically a new virus, so humans have not had experience on how to deal with that virus, so we learn as we go, but I do think we are already in our way out of the pandemic phase of Covid-19.

We are not going to erase Covid-19 from the phase of the Earth, we are going to continue to coexist with the disease. Most likely, it will become a seasonal endemic disease, like influenza. So, every year, especially during cold seasons, when people spend more time indoors and are more exposed to contagion, we are going to have to reactivate certain measures. For example, in Asia, which had an earlier experience with coronavirus, every year now people put on their face masks. It’s like taking out scarves or jackets. We should do the same. We have not succeeded at this because the use of face masks has been politicized, so we need to depoliticize it.

To finally get out of the pandemic phase, the two keys are: to maintain and accelerate the pace of vaccination in Mexico, which unfortunately has slowed down.

Second, it is necessary to bring in new vaccines, the bivalent ones that protect against the Omicron variant, which is already the dominant one and is very likely that it will remain the dominant one, and the original strain.

And third, we must participate globally in all the discussions that are taking place worldwide about improved schemes, to be better prepared for the future; that is something in which Mexico has had little to no presence. We don’t depend solely on what we do in Mexico, but also on what other countries do, and if there are no clear rules, and mechanisms to ensure that the rules are followed by all, we are left exposed and vulnerable.

What do you think we need to do to be able to prevent a pandemic in the future?

First of all, we need to give elements to the World Health Organization (WHO) to be able to sanction countries that don’t comply with regulations, because they put the whole world at risk. For example, in this pandemic, there was a delay with the Chinese authorities in notifying about the outbreak, and, nevertheless, there was no sanction.

The irony is that now, if a country reports an outbreak, as Mexico did in 2009, there are significant economic consequences: travel, tourism, and commerce are suspended, for example, so there’s a strong incentive not to report it. All of that can change. The World Bank Group has proposed having an insurance mechanism where if there is an outbreak in a country and by reporting it suffers economic losses, the insurance is activated to help them cope.

The rules are good, but if nothing happens to those who don’t comply and there’s nothing to protect those who do comply, we have an upside-down world. The incentives are upside-down.

The second thing is to establish a force that is on standby and ready to mobilize; a kind of NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) of epidemiology that, when there are signs of an outbreak, can be quickly mobilized, especially to aid countries that don’t have a good response capacity.

Third, we must have technology platforms ready so that as soon as a new virus appears, and the genome is sequenced, we can literally “plug in” the genome to a computer and start producing tests, vaccines and antivirals immediately. In this pandemic, for example, tests took a long time to be created, and valuable time was lost.

And fourth, I think we have to very seriously consider the disproportionate effect the pandemic had on so-called essential workers, who are typically low paid, but without whom societies can’t function. All the people who were in charge of keeping basic services running. We call them essential, yet we don’t value them enough. I think we have to reflect on how to better recognize their efforts and improve their pay. I would say we need to do the same thing with health personnel.

Mexico has the highest percentage of Covid deaths among health personnel. This reflects the little value authorities place on health workers. So, if we want to be better prepared, we have to improve how much we pay doctors, nurses, technicians, and other essential workers. They cannot be asked to be and act like heroes and get rewarded as if they were marginalized sections of society. I think those are some of the measures that could give us a safer world.