For generations, doctors and healthcare providers have relied on a simple equation—weight divided by height squared—to assess whether a child is overweight or obese. But a new study led by Mexican researchers is challenging that approach, calling on the medical community to rethink how we protect children’s health.

The research was inspired by a recent report from The Lancet & Endocrinology Commission, where an international group of scientists proposed modernizing how we classify weight-related metabolic disorders.

Instead of labeling people as “normal weight,” “overweight,” or “obese,” they suggest a new system: metabolically healthy, preclinical obesity, and clinical obesity.

The authors also propose going beyond BMI by including measurements of muscle mass and metabolic markers—such as blood glucose levels—to determine better whether a person, especially a child, has a metabolic condition.

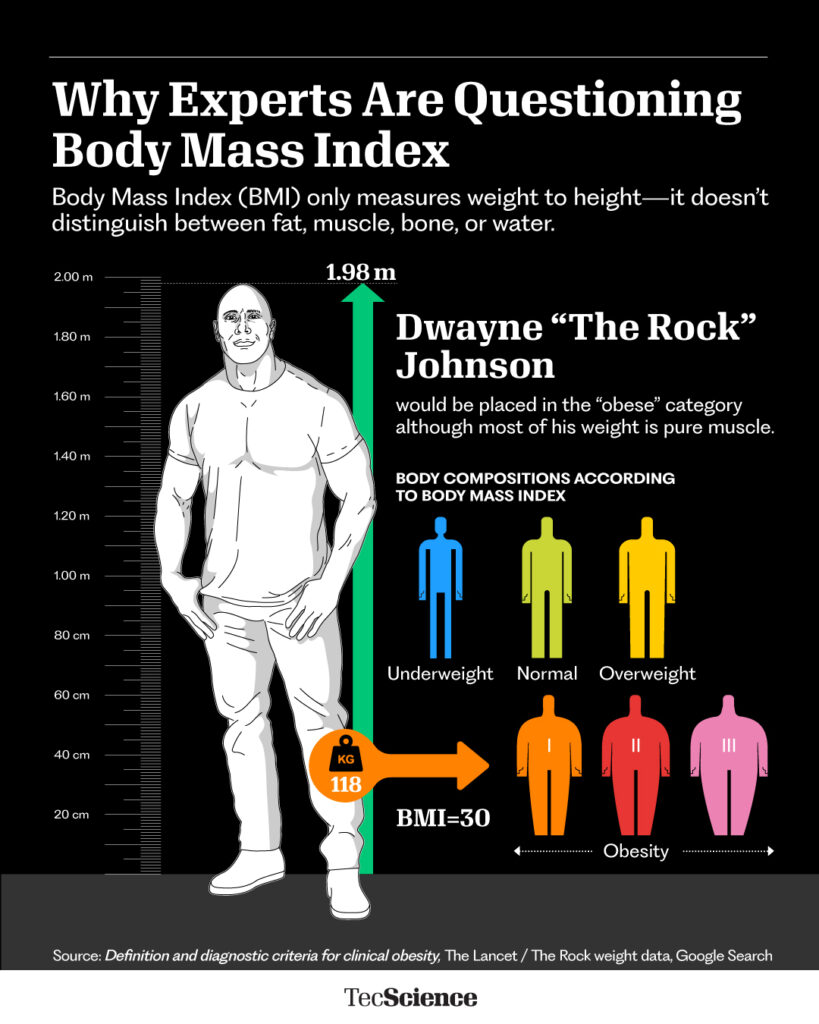

BMI is Simple, But Often Misleading

BMI is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared. For adults, that number directly places them in a category. For children, it’s compared to standardized growth charts based on age and sex.

But here’s the problem: BMI can’t distinguish fat from muscle.

“Some people score high on BMI, but they’re not actually obese,” explains Cipatli Ayuzo, a pediatrician and researcher at TecSalud and Hospital Zambrano Hellión. “Think about athletes like Canelo Álvarez or The Rock—they have a lot of muscle mass.”

The new study, which Ayuzo co-authored, proposes a more complete method for evaluating metabolic health in children.

Not Every Child with a High BMI is Unhealthy

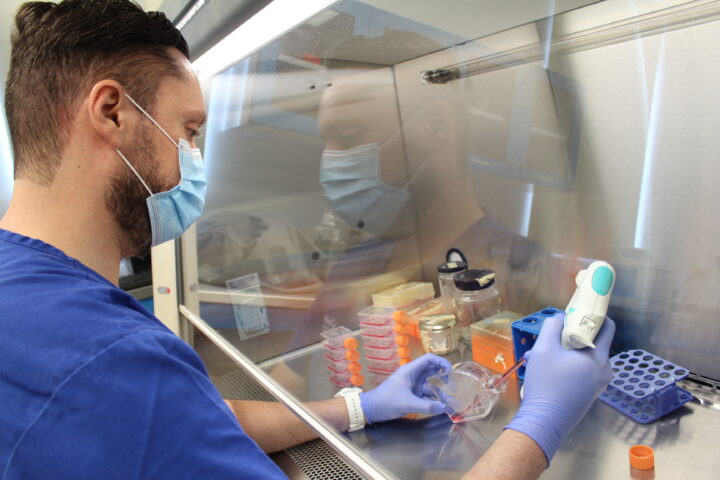

The team recruited 111 physically active children, ages 6 to 11, who played in a soccer league in Monterrey, Mexico.

Each child underwent several tests, including weight, height, bone mass, body fat percentage, and muscle mass. Researchers also collected blood samples to measure glucose and cholesterol levels.

Using this broader set of data, the team applied the 2025 Obesity Classification Framework (2025-OCF)—a new diagnostic tool inspired by The Lancet report—to offer a more accurate view of each child’s health.

The contrast was striking:

Using BMI alone, 48 children were classified as normal weight, 40 as overweight, and 23 as obese.

Using the new classification, 56 were categorized as normal weight, 51 as having preclinical obesity, and only 4 as having clinical obesity.

“There were kids with a lot of muscle who had no metabolic issues,” says Ayuzo, “and others who looked healthy but had concerning metabolic markers.”

Some of the children previously labeled as overweight or obese simply had more muscle or heavier bones. Meanwhile, some thinner kids showed early signs of metabolic imbalance.

What this Means for Parents, Pediatricians, and Policymakers

Looking ahead, the researchers recommend supplementing BMI with other indicators—such as waist circumference or bioimpedance scales that estimate body fat percentage. This is especially important for children who play sports or have larger body frames.

They also call for a less simplistic view of weight:

“Not every child with a high BMI is at risk, and not every child with a ‘normal’ BMI is healthy.”

These findings serve as a reminder that children’s health can’t be measured with a one-size-fits-all approach. By analyzing both the body and metabolism more thoroughly, we can avoid misdiagnoses, unnecessary interventions—and perhaps most importantly, detect risks early and without bias.

“If a child goes to the doctor and is told they’re fat or obese, that label can stick with them for life,” Ayuzo warns. “And maybe all they had was extra muscle mass.”

In a world where childhood obesity rates are rising, having fairer, more precise tools isn’t just a technical upgrade—it’s a better way to care for our kids.

“This study has the scientific foundation to say: ‘I measured every aspect, and I can tell you this is a healthy child—just with a bigger body,’” says Ayuzo.

Interested in republishing this story? Reach out to our content editor at marianaleonm@tec.mx