Autism is a condition that can completely reshape a family’s dynamics when one of its members is diagnosed. Beyond that, it often takes a toll on the mental health of parents or caregivers, who may experience anxiety, stress, and depression along the way. A comprehensive approach that not only focuses on meeting the needs of the child with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) can make all the difference.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), autism is a group of conditions related to brain development, marked by unusual patterns of behavior that make social interaction and communication difficult. The organization estimates that roughly one in every 100 children worldwide is on the autism spectrum. In Mexico alone, that number exceeds 400,000 children.

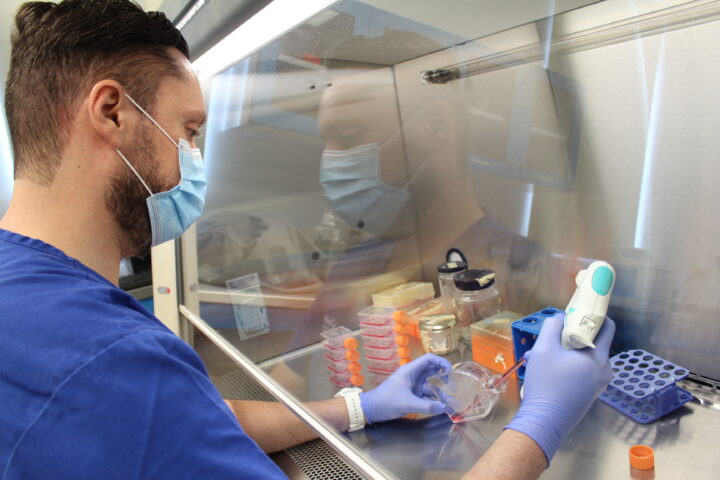

Juan Francisco Lozano, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at Hospital Zambrano Hellion and director of the Down Syndrome Clinic at the Pediatrics Institute in TecSalud, points out that one way to provide well-rounded care is through family-centered care. This model encourages collaboration among clinical providers, mental health support for parents, and training for at-home interventions.

“The goal is to ensure the best possible quality of life for both the patient and their family,” he explains. “It’s all about respecting the needs and objectives of every area involved because the therapeutic goals often don’t necessarily align with what the family wants or needs. So, decisions are made to offer individualized and personalized care for that specific patient diagnosed with autism.”

Family-Centered Care: A Comprehensive Approach to Autism Spectrum Disorder

Today, most cases of autism are identified during childhood, when boys and girls begin developing various skills. During this period, therapeutic intervention strategies are designed—not only for the child but, through this model, with the family’s needs in mind as well. Factors such as socioeconomic status, cultural background, family dynamics, and lifestyle are all considered, explains Lozano.

“Sometimes, we may recommend an intervention to support language development or behavior management, but the family might have a different, more pressing need,” he points out. “For instance, sensory issues—maybe they struggle to bathe or dress their child, or the child is bothered by certain noises. Suppose we overlook these challenges and fail to involve the family in the therapeutic recommendations. In that case, we won’t be providing an intervention that truly meets the goal of improving the child’s and the family’s quality of life.”

When designing effective interventions, specialists rely on the ICF model—the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health—developed by the WHO. This framework looks at the child’s skills and daily functionality, as well as the obstacles they may face when trying to participate in recreational, educational, or family activities, among other things. Beyond identifying these areas needing support, the family-centered care model also asks families directly about the difficulties they would like to address.

By combining these perspectives, realistic, clear, and attainable goals are set based on the child’s development. This approach includes work models where parents and caregivers actively participate in psychoeducational sessions so they can be fully informed and better understand the diagnosis.

Additionally, the model provides support throughout the acceptance process by offering psychological counseling, grief therapy, and emotional support to help families achieve emotional stability.

Lozano explains that this approach encourages parents and caregivers to get involved and feel empowered. They receive coaching and hands-on training in every intervention strategy so they can implement them at home. That way, the two or three hours a child might typically spend in therapy sessions can effectively grow to 25 or even 50 hours when therapy is carried out at home.

Mental Health Challenges for Parents and Caregivers

Studies show that parents and caregivers of individuals with ASD often experience anxiety, sadness, or guilt. On top of that, they may feel isolated due to a lack of understanding or support from their social circles. Their mental health can deteriorate over time as a result of fatigue and exhaustion caused by the constant pressure of managing behaviors associated with the disorder.

One of the biggest hurdles, Lozano says, is the process of acceptance. Even if parents suspect something may be going on with their child, many families are simply not ready to hear a formal diagnosis. The transition toward starting a therapeutic program can take time—sometimes six months to a year.

During the evaluation process, uncertainty inevitably creeps in. Families begin to wonder what the outcome will be, and often, their expectations don’t match the diagnosis. This disconnect can lead to disbelief and make acceptance even more difficult. It’s also common for anxiety to surface during this phase.

“Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the cycle starts all over again,” the specialist explains. “Now there’s uncertainty about what autism means for their child’s future: What will happen? What will their life look like when they grow up? And then the anxiety: Can I give my child everything they need?”

Receiving a diagnosis can trigger a grieving process for parents and caregivers—though not the same as grieving the loss of a loved one. It’s a unique kind of grief that resurfaces at different stages throughout their journey.

For instance, when families try to enroll their children in school, they often face obstacles in finding an academic environment that aligns with the expectations of the education system. Lozano points out that these recurring challenges over time can create multiple stressors for families and may eventually lead some family members to struggle with depression.

In this context, the family-centered care approach strongly emphasizes supporting the mental health of parents and caregivers, recognizing that their relationship with the child is a key component of the child’s overall care. When parents are dealing with anxiety, they may become more reactive—or, conversely, more withdrawn and less tolerant—when their child exhibits socio-emotional behaviors like frustration or tantrums. A parent living with depression, for example, may have less energy to take their child to therapy or simply to play and engage with them.

Lozano emphasizes that children diagnosed with ASD need highly positive and enriching interactions with their parents. While focusing on developing the child’s language, cognitive, and learning skills is crucial, caregivers’ psychological needs should not be overlooked. “We have to address that part too, so the entire ecosystem around the child can function in the best possible way,” he says.

Beyond the family-centered care model, other resources and tools are available to parents and caregivers. For instance, the WHO offers free online guides and training programs to help families develop the skills needed to care for individuals with ASD.

The Path Towards Family-Focused Care

Lozano suggests that when families begin to suspect a possible autism diagnosis, the first step should be to consult their pediatrician—the person who knows the child’s medical history and family context best.

“They’ll be able to identify specific needs and guide the family toward the right resources based on those observations,” he explains. “There are screening tools available—essentially questionnaires—that help detect whether there are traits or signs that may suggest a possible autism diagnosis.”

The most common screening tool is the M-CHAT, which provides a score indicating whether the child should be referred to a specialist. If necessary, professionals who can offer a formal diagnostic evaluation and develop an intervention plan include pediatric neurologists, child psychologists or psychiatrists, pediatric rehabilitation specialists, or developmental pediatricians—ideally, those with expertise in autism, Lozano notes.

Despite these available options, the specialist points out that high-quality services and evidence-based models, such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy, are often associated with high costs. This leads to therapy centers and specialized services concentrated in areas with higher socioeconomic status.

“Autism doesn’t care about socioeconomic status—we all have the same risk of having a child with ASD,” Lozano adds. “There are families who, in many cases, need these high-quality services the most but face significant barriers in accessing them.”

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx