The search for a cure for HIV has been one of the most complex challenges of modern medicine. However, a new scientific collaboration between the Ragon Institute in Massachusetts and Tecnológico de Monterrey could open a new path.

During the first joint symposium between both institutions, researchers revealed a proposed plan to begin clinical trials in Mexico for a new therapeutic vaccine against HIV.

The vaccine, developed by the laboratory led by Gaurav Gaiha of the Ragon Institute, is based on network theory—a branch of applied mathematics commonly used in engineering and computer sciences—to identify the weakest structural points of the virus.

This methodology has allowed for the design of a therapeutic vaccine that seeks not only to control the virus, but also allows people who live with the virus to stop their daily medication without a viral rebound.

The Science: When Biology Meets Topology

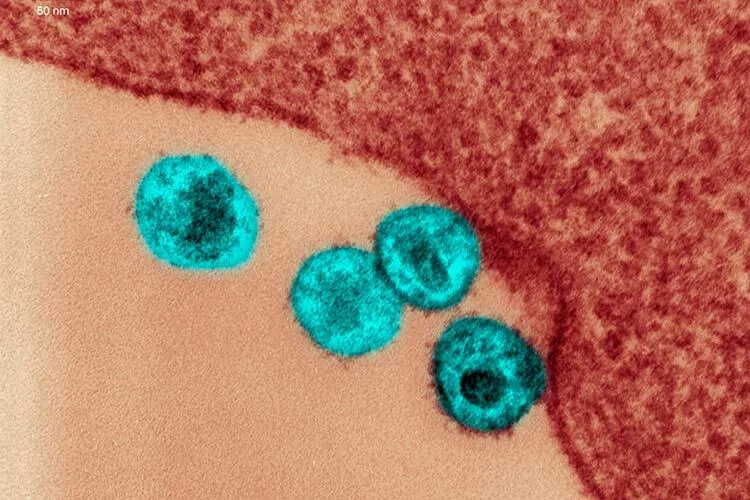

The biggest obstacle in developing effective vaccines against HIV has been its capacity for mutation, explained Gaiha. The virus changes so quickly that, by the time the immune system learns how to attack it, the pathogen has already altered its appearance.

“In reality, the virus is almost in all cases able to outpace the human T-cell response,” Gaiha added.

Still, the research presented at the symposium suggests that this variability has structural limits.

Gaiha’s team applied network theory algorithms to analyze the structure of HIV proteins. Instead of focusing on the linear genetic sequence, they studied the virus as a network of interconnected nodes.

“The idea was to take the protein structure and transform it into a network and then determine which are the critical amino acid residues and the inter-residue interactions,” he explained.

With this analysis, they identified what they called “highly connected residues.”

These are specific amino acids that act like load-bearing columns in a building. They’re so critical to the structural stability of a virus that it can’t mutate without self-destructing or losing its ability to replicate.

The objective of the emerging vaccine is to train T cells, which fight infection, to ignore parts of the virus that are constantly changing and focus their attack on the virus’s fixed structural nodes. If the virus tries to mutate those points to escape the immune system’s attack, its structure collapses, and it stops being infectious.

“With this tool in hand, we were very excited to apply this to HIV, obviously a pathogen of major global relevance,” said Gaiha.

He also explained that the strategy is based on the so-called “elite controllers,” a small group of people who live with HIV and are capable of controlling the virus naturally without medication. The Ragon Institute’s research has shown that the immune systems of these individuals attack precisely these highly connected networks.

A Functional Cure

As opposed to a preventative vaccine, the proposed clinical trials for Mexico look for a “functional cure” for HIV.

Currently, the people living with the virus depend on antiretroviral therapy (ART) for life. If they stop taking their medicine, the virus that remains dormant in the body multiplies again.

A functional cure won’t necessarily eliminate every viral copy in the body. Instead, it trains the immune system to maintain the virus suppressed indefinitely without the need for external drugs.

Based on what researchers shared at the symposium, the goal is to administer the vaccine to patients who are stable enough under antiretroviral treatment, induce a strong T-cell response against these structural targets, and eventually wean them off the medication under medical supervision.

The current trials of this method are taking place in sub-Saharan Africa, where the subtype, or clade C of HIV, predominates. In July, they vaccinated their first volunteer in Zimbabwe. Currently, they have inoculated 73 individuals in the Mutala clinic.

Still, to validate the vaccine’s global efficacy, it’s important to test it against clade B, the subtype that predominates in North America and Europe.

That scientific need is one of the reasons why they are looking to conduct clinical trials in Mexico.

The regulatory challenges have also played a role in this decision. During the symposium, researchers discussed how the process to begin new clinical trials in the United States, under the FDA, is slow and expensive.

They see Mexico as an opportunity to conduct trials with the same scientific rigor but a more flexible regulatory framework. “If we could have the picture of the first patient dosed in Mexico, I think that would be phenomenal for next year,” said Gaiha, marking 2026 as the goal for the collaboration.

The VIHVA Clinic

In order to execute these complex trials, the team requires a first-rate clinical partner. One of the potential sites for this operation could be the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Salvador Zubirán, represented at the symposium by Brenda Crabtree. She’s a researcher with 20 years of experience in HIV research and a professor of the HIV program at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Under her leadership, the VIHVA Clinic has evolved from a center for basic care founded in 1986, when there were no HIV treatments, into a cutting-edge research center. The clinic was the first in Mexico to implement universal antiretroviral treatment in 2014, before many other countries in the region.

Today, the VIHVA Clinic has 1,600 active patients who have used their services at least once this year.

Sixty percent of their patients live with advanced HIV, making them a referral center and one of the biggest clinics in Latin America. The majority of their patients arrive having never received ART treatments.

The clinic is certified by the ACTG, a global network of clinical trials that aims to improve HIV treatments and their comorbidities. They received this accreditation in 2021, validating their standards against those of the National Institutes of Health in the U.S. and laying the groundwork for this experimental vaccine.

The Road to a Clinical Trial

The road to a clinical trial is just one part of a broader collaboration that is already underway. As the symposium organizers said, the agreement between Tec de Monterrey and the Ragon Institute includes immediate investment in human and scientific capital.

The first milestone is set for January 2026, when the first generation of postdoctoral fellows from Tec will land in Boston for their three-year stays. These researchers will act as a bridge between the two institutions.

At the same time, they announced that three pilot grants have been funded for collaborative projects, with the promise to open future calls for proposals with broader financing next year.

“I hope that this collaboration between our two institutes will launch programs that will help fill that space to realize the potential and growth for science and research in Mexico,” said Alison Ringel, researcher with the institute.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx