There is a type of stress experienced when a child faces a challenge that is difficult, but manageable, such as the first day of school, a sports competition, or an important exam. This type of brief or temporary stress is called positive stress.

However, when an adverse situation is severe, repetitive, and chronic —and the child does not have the type of support in their environment to help cushion the impact— it produces toxic stress. This has biological effects on the brain and body that can have lifelong consequences, ranging from academic problems and social difficulties to chronic mental or physical health issues.

Pat Levitt, Chief Scientific Officer, Senior Vice President and Director of the Saban Research Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, explained this in an interview with TecScience ahead of his participation in the Second International Early Childhood Forum, organized by the Early Childhood Center at Tecnológico de Monterrey and FEMSA Foundation.

“I was part of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, that worked for three years to try to make clear the difference between occasional stress and chronic stress. What we found is that stress is not always bad. So, how do we define it? What we decided was to use terminology that would be done in the context of a taxonomy, and we defined three levels of stress,” Levitt said.

Toxic Stress, Positive Stress

- Positive stress. “For example, when a five-year-old child is very shy and has to get up to go to kindergarten and feels nervous, which doesn’t happen on weekends. This stresses them for a moment, causing brief increases in heart rate and the secretion of the stress hormone (cortisol), which activates us a little, speeds up metabolism, and makes us alert to run or face the problem. In this type of stress, cortisol levels remain elevated for a while but then drop, and everything returns to normal.”

- Tolerable stress. “This generates a response — severe but temporary — to stress, as it is buffered by supportive relationships. It’s when you have situations like occasional abuse or neglect, which are serious and severe early adversities, but you have supportive and caring relationships around you” that help cushion what would normally be a major problem.”

- Toxic stress. This happens when stress is chronic or persistent, and the child does not have the type of support in their environment to help cushion the impact, leading to prolonged activation of stress response systems. Cortisol levels remain high for an extended period, damaging physical and mental health.

Building a House

Just as a house is built, so is a child’s brain: first, the foundations are laid, then the rooms and electrical wiring. In fact, during the first years of life, the “wiring” of the brain grows at an astonishing rate, making up to two million neural connections per second.

However, toxic stress can damage the architecture of a developing brain and affect a child’s senses and thoughts, as well as cause health problems later in life.

Levitt put this into perspective with an analogy: “A developing child is like building a house. If, during construction, you decide you need more electrical outlets, it’s easier to add them when you are building than waiting until the house is finished because then you’ll have to call the electrician.”

He continued with his comparison: Lack of buffering during the period when a child’s brain is under construction is like “when a house under construction faces extreme weather and you don’t have a tarp to put over the house and protect the materials, and the house gets damaged.”

“Sometimes the damage is so great that you have to start over. You can do that with a house and start from scratch if you have the resources, but you can’t do that with a child. You can’t go back in time. So the damage is already done.”

Cellular Response to Toxic Stress

“Not all stress is bad,” the scientist reiterated. “There’s positive stress that we all experience as children when we go through uncomfortable and new experiences, but we learn to deal with them. The stress response system is fine-tuned to handle novelty, increasing cortisol and adrenaline, which provide energy for cells to respond, and then return to baseline.”

He explained that it’s like the immune system: you catch an infection, the immune system is activated, T and B cells produce antibodies, fight the infection, and then return to baseline. But if they don’t return to normal, it leads to autoimmunity, a disease where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells.

“From zero to three years old is a time when the brain is battling with the body for energy. A lot of energy is needed to build the developing brain”, and for this reason, negative experiences can have a great long-term impact. But if there’s a buffer or positive experiences, you can have a really positive outcome.

In this regard, the activation of positive stress is important to generate energy for the cells, but if this is continuously activated, something called the cellular danger response (CDR) can emerge, allowing the cell to protect itself, stay alive, and resume functioning once the stress ends. However, the CDR must maintain a balance, or it can produce an allostatic load, an overload of biological and physiological functions.

Research Advancements

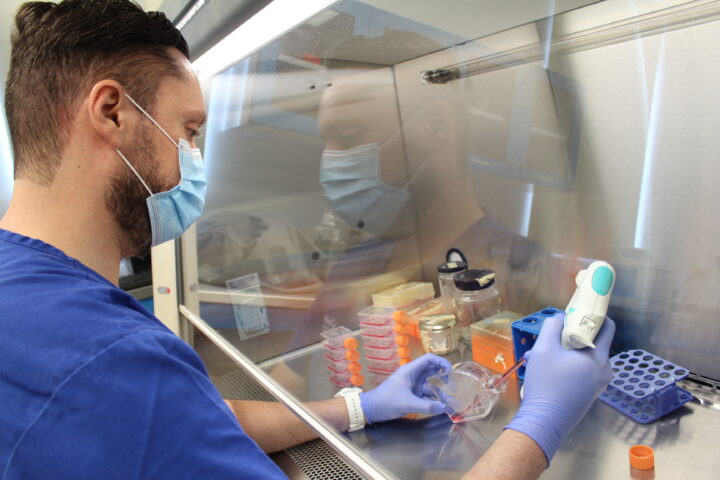

During his keynote speech, Pat Levitt showed some recent scientific works, some developed collaboratively between Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the Early Childhood Center at Tecnológico de Monterrey, which investigate potential methods for early detection of toxic stress.

These research projects highlight the connection between toxic stress and chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, cancer, as well as cerebrovascular, coronary, and kidney diseases.

“There is a large body of scientific literature demonstrating the links between early life adversity, toxic stress, and poor health outcomes”. However, he said there are still no consensus guidelines for diagnosis or therapies and treatments for toxic stress.

Levitt concluded his keynote by briefly explaining some advancements in early detection of toxic stress. He mentioned a study that could detect oxidative stress in infants between six and twelve months old using a biomarker obtained from urine. He also mentioned another study that measures the number of copies of mitochondrial DNA, since when mitochondria are stressed, they tend to divide within the cell, indicating that an infant is in a vulnerable state.