In Latin America, walking is one of the most important means of transport, representing 30% of all trips made by citizens. Of these, those who walk the most are children, but little is known about the conditions of their journeys. Walking to School in Latin America is a project that seeks to understand the issue.

“We want to understand the challenges faced by children who live in the outskirts of cities on their way to school,” says Aleksandra Krstikj, research professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) and leader of the project.

According to her, mobility in Latin America, especially in the outskirts, is limited because most streets are designed for motorized vehicles, leaving aside tricycles, bicycles, skates or scooters, as well as pedestrians.

In addition, public transportation is often insufficient and unsafe, so children do not use it regularly.

Although there is knowledge about the conditions in which adults walk, there is a void of information regarding children mobility and how they feel when walking the streets, how much and how they do it.

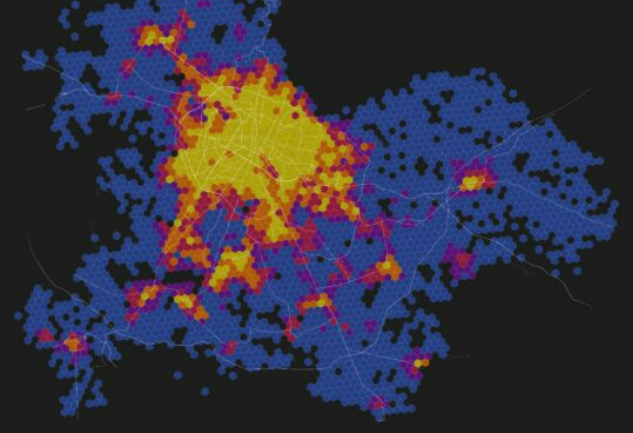

To understand this, the team led by Krstikj analyzed the mobility on foot of children who attend primary school in three Latin American cities: the State of Mexico, in Mexico, Medellín, in Colombia, and Recife, in Brazil.

The project is being carried out by EAAD, the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (CIDE), the Urban Requalification and Resilience Program in Areas of Socio-Environmental Vulnerability (ProMorar), the Center for Urban and Environmental Studies (Urbam) and was funded by Volvo Research and Educational Foundations.

A Mixed Methodology to Understand the Problem

According to Krstikj, although there are some guides in Latin America to make school environments safe, most of them focus on proposing solutions that are imported from other countries and do not really focus on understanding the challenges children face when the walk to school in the region, so the proposed solutions often fail.

“Our research focuses on shedding light on this problem, so we can later design solutions and public policies that are appropriate to the context of our region,” she explains.

To do so, the team used a mixed method where they did a quantitative analysis to measure how much children and their companions walk to school, how many kilometers they travel and what the territory they travel is like.

On the other hand, they did a qualitative analysis with surveys, interviews and educational activities where they asked children and their primary caregivers – parents, mothers, siblings or grandparents – how they experience these walks.

Although the results of this work are still in process, they already have some ideas of what challenges they face in the State of Mexico.

In general, when they walk the streets, children look for spaces where they can play, as it is an important way of interaction to them. They also look for green spaces with shade and places where they feel safe.

“Unfortunately, parks, trees and safe areas are generally lacking in the outskirts of the country,” says Krstikj.

Children are also afraid of motorcycles, cars and trucks, which are the main means of transportation in the country.

Primary caregivers say they do not feel safe letting them walk to school alone and have to organize themselves in community to find solutions, as many have to leave to work and the state does not provide safe transportation for children.

The Importance of Walking to School

Once their research is complete, the researchers’ goal is to publish articles and a practical guide to design interventions in Latin American cities that are aimed at ensuring safe and active mobility so that children can walk to school and other places freely.

This is important for children’s health, since according to the researcher, different studies have found that those who use the car more often have less physical coordination and orientation.

“Walking not only improves their quality of life, it also increases the child’s pride in belonging to a community,” says the researcher.

In the future, they also seek to ally with government agencies and schools to plan public policies and improvements to cities that promote better mobility in the outskirts, putting special emphasis on children.

They also want to raise awareness and educate societies through community activities on the importance of considering children when planning a city.

“Children are citizens too and have a right to the city, but no one asks them what they need and they usually don’t have a voice,” says Krstikj. “However, they do deserve safety for the journey they make to school almost every day.”

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx.