Ensuring that all people can access quality health services is key to guarantee a prosperous future for humanity. However, in Mexico, indigenous populations face systematic discrimination and health inequalities that prevents them from taking proper care of their health.

“Despite the fact that the constitution states the equality of citizens, in practice we observe a highly stratified form of social organization,” says Sergio Meneses, a researcher at the National Institute of Public Health, in an interview with TecScience.

According to him, historically, indigenous populations have experienced constant discrimination and racism, which is visible in the daily life of the country, but can also be measured with different economic and health indicators.

“They have higher rates of poverty, illiteracy, infant mortality and a lower life expectancy,” says Meneses. In terms of access to health services, “it is lower and they face worse quality of care.”

Thus, universal health coverage –which implies that all people have access to quality health services whenever they need them without financial hardship– one of the Sustainable Development Goals proposed by the United Nations to guarantee a better and more sustainable future for humanity by 2030, is far from becoming a reality in the country.

With this in mind, Meneses and a multi-institutional group of researchers, made up of Rocío García, from the School of Social Sciences and Government at Tec de Monterrey, Rafael Lozano, from the Faculty of Medicine at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM); Laura Flamand, from the Center for International Studies at Colegio de México and others, analyzed three health expenditure indicators and how they vary between indigenous and non-indigenous populations.

“We tried to account for how the gaps between these two populations have been maintained throughout the years,” says Meneses.

Disparities in Access to Healthcare in Mexico

To demonstrate that there is a nationwide systematic inequality impacting access to health care for indigenous populations, in their study, the researchers used three healthcare expenditure indicators, which they analyzed over the course of twelve years. These were catastrophic, impoverishing, and excessive health expenditures.

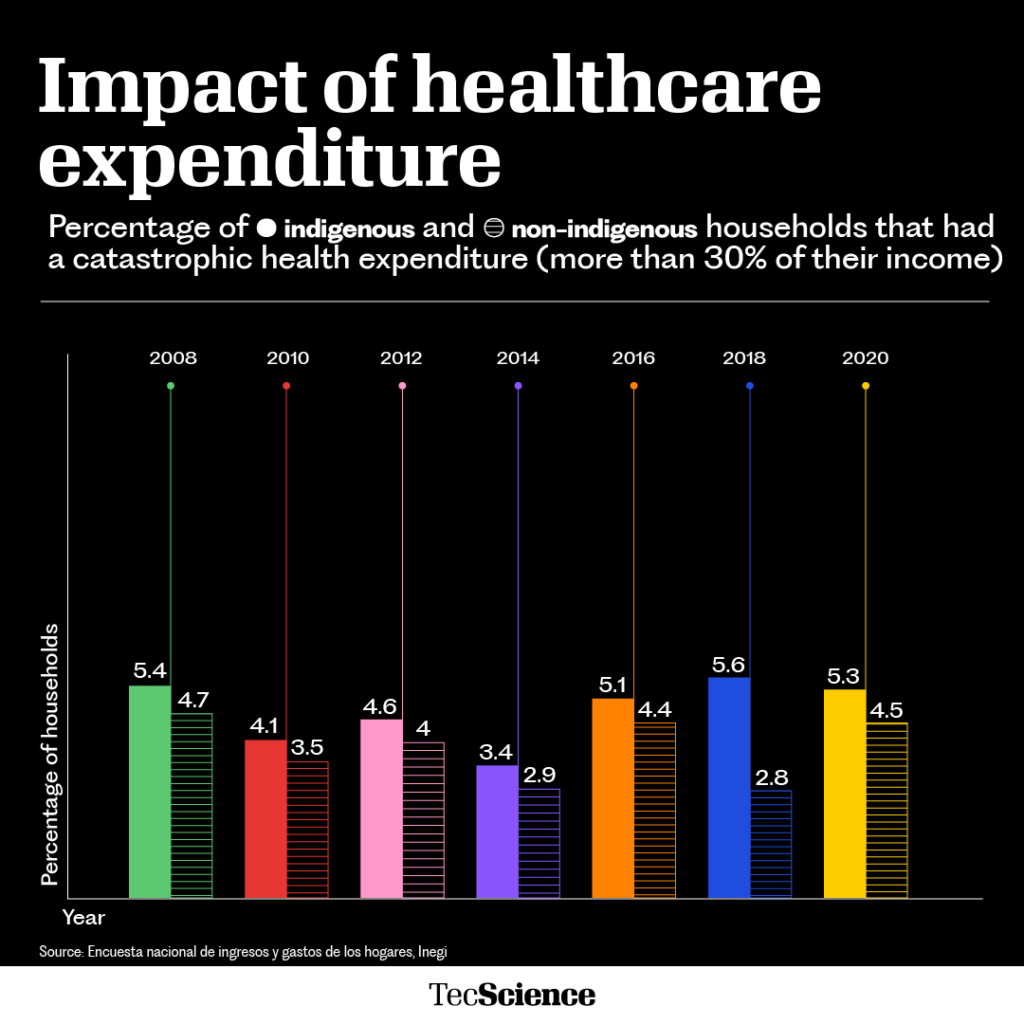

Catastrophic health expenditure means that families spend 30% or more of their income on the medical care of one of their members. Impoverishing health expenditure occurs when families invest an amount on healthcare that takes them below the poverty line. And finally, excessive health expenditure is one that exceeds 10% of the total household spending.

Using information from the National Household Income and Expenditure Survey (ENIGH), carried out every two years by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Inegi), they analyzed the trends in these markers from 2008 to 2020, making a comparison between indigenous and non-indigenous houses.

“We found that, at all times, there is an inequality in access when you compare them,” explains Meneses. “Indigenous households always incur in greater catastrophic, impoverishing and excessive health expenditure.”

When reviewing catastrophic health expenditure specifically, the researcher points out that, from 2008 to 2014, a downward trend was observed in this indicator, but that, starting in 2014, it has been steadily increasing.

According to Meneses, this is partly due to the fact that from 2008 to 2014, Seguro Popular still existed, a program aimed at providing health insurance to people who did not have one, whether it was public or private.

“In 2014, the public investment in health stagnated and, finally, in 2020, this health insurance disappeared completely,” he says.

Financial Protection Mechanisms for Indigenous Households are Lacking

For Meneses, their research shows that indigenous populations are always at a disadvantage when it comes to taking care of their health.

This is evident in the fact that although the different indicators have changed over the years, indigenous populations have remain the most affected.

“Although catastrophic spending in indigenous and non-indigenous households decreases, the inequality between them remains,” says Meneses.

This is worrying, because it means that there is no real progress towards equality in the country. “One might think that the 5.3% of catastrophic health expenditure in indigenous households is not that high, but we are talking about millions of people,” he says.

According to the expert, this shows that protection mechanisms are needed to ensure that indigenous households can access sufficient and quality medical services without it damaging their economy.

This lack of access to a good health system is a consequence of the systematic discrimination and racism that exists towards these populations. “The stratified structure of our society permeates all areas of social life, including the health system and public institutions,” says Meneses.

In order to eradicate these inequalities, the country must have financial mechanisms that protect the most vulnerable populations.

How to Begin Reducing Inequality in Healthcare Access

With this evidence in mind, the research group proposes two main measures to start reducing these gaps: having a health insurance for those who do not have public or private coverage, with clauses that give preference to populations that live in inequality, and including legal actions and mechanisms against discrimination towards indigenous populations.

Currently, in Mexico, there are approximately 80 million people who do not have social health insurance, emphasizes the expert.

Contrary to what has happened in the country, “it is desirable that the health budget has an increasing trend,” says Meneses. “We also want it to be used efficiently, we do not want wastefulness.”

To get there, the first thing the country needs is to recognize that indigenous populations have been subjected to racism and discrimination historically.

“The history of this social order traces back to the colony,” says Meneses. “If we want to modify this form of organization, we must first recognize we’ve been living in it and then act accordingly.”

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx