In the outskirts of Mexico City, getting fresh food that allows having a healthy diet is much more difficult than finding ultra-processed food or high in refined sugars. This lack of accessibility accentuates the inequalities that exist there.

“What you find most in the peri-urban area are potato chips or canned food, which are bad for your health when consumed in excess,” says Alexandra Krstikj, research professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) at Tec de Monterrey.

Interviewed by TecScience, she and two of her colleagues (Gerardo Contreras Ruiz Esparza and Christina Boyes), recently published the results of their research to understand the root of this lack of access to healthy foods in the Mexican capital and how to solve it through urban planning.

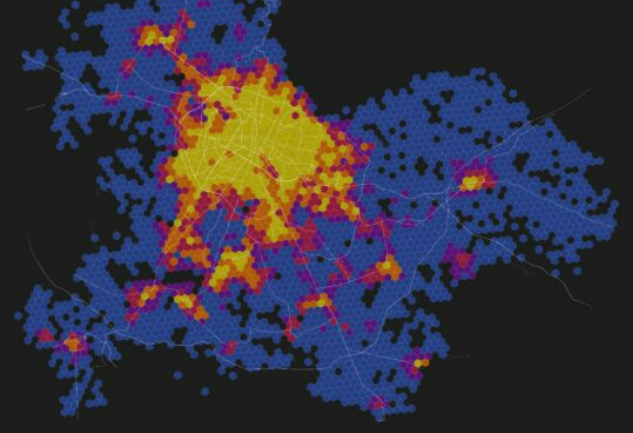

From September to December 2022, they conducted surveys to analyze the cost of food, availability of flea markets and mobility from different areas of the city to access healthy food.

The idea is to use this information to propose a series of steps that will allow Mexico City and its periphery to go from having mostly food swamps to nutritious landscapes.

“Food swamps are places where fresh, unprocessed food is scarce compared to ultra-processed foods,” explains Krstikj. On the other hand, nutritious landscapes are those where fresh foods are abundant, locally produced, affordable, and easily obtained.

Nourishing landscapes and food swamps

Among their findings, currently, in the periphery of the city, 23% of the minimum wage is required to be able to purchase fresh fruits, vegetables, meat or fish.

On the other hand, in areas like Atizapán de Zaragoza, there are around half a million people and only 40 tianguis (local markets) with fresh food available. Meanwhile, in Mexico City, there are around 1,300.

Furthermore, the lack of accessibility caused by limited or deficient public transportation and the lack of sources of fresh food that can be reached on foot makes the problem even more complex.

The solution lies in promoting local production, both in the city and in the urban-periphery, to increase their resilience and reduce inequalities. The perfect candidate to achieve it is an urban garden project.

“If urban gardens cannot cover all the demand, it would be ideal to complement it with establishments such as flea markets,” says Krstikj.

There is a local law, established in 2016, regarding that urban gardens can enable local food production. However, this regulation and other public policies focused on the food system do not apply in the urban periphery.

“The peri-urban area belongs to several states and the public policies are different in each one, if you don’t unify them, then how can you organize mobility and something as important as the production and consumption of food?,” says Krstikj.

Something important to consider is that for urban gardens and street markets there must be urban planning project to enable food distribution.

In the United States, for example, urban gardens produce enough food to feed millions of people, but much of it ends up being thrown away due to the lack of a good distribution system and poor acceptance by the population.

Urban gardens to combat the food crisis

Krstikj explains that the recipe to build a nutritious landscape in Mexico’s city urban periphery consists of changing the chip in urban planning to contemplate the production and distribution of food.

Second, establish unified public policies that encourage the consumption of fresh, unprocessed foods, facilitate access to them by improving mobility and regulating the prices of fresh foods to make them more affordable.

Third, highlight food education for children and the elderly. “Schools have a key role because habits and attitudes of children are formed there,” says the expert. Older adults have the knowledge to use local ingredients in food recipes.

According to the researcher, the food crisis in the globalized world is as bad as the climate crisis, and they are linked. The way we produce food today, through livestock and agriculture, has historically been behind the climate crisis. On the other hand, without a healthy environment, the production and distribution of healthy foods is becoming more complex every day.

“From our trenches, architects have to put all our efforts into eliminating the bottlenecks that prevent people from consuming healthy foods, to better plan cities and improve the resilience of communities,” says Krstikj.

“We need urban planning to include everyone, not just a few, so that no one is left without their right to have access to healthy food”, she concludes.