According to INFONAVIT itself, around 650,000 homes —bought with credit from the Institute— are abandoned because they lack basic services and security, they’re far from the buyers’ workplaces, and there are no public transportation services, among other issues.

In order to address this problem, Tec de Monterrey’s Observatory of Cities at the School of Architecture, Art, and Design (EAAD) has developed a Proximity Index that it delivered to the National Workers’ Housing Fund Institute (INFONAVIT) to verify proximity to schools and health and supply services (urban facilities).

Its creators sayit’s a tool that can be applied to 75 Mexican cities which could contribute to people’s right to access adequate housing.

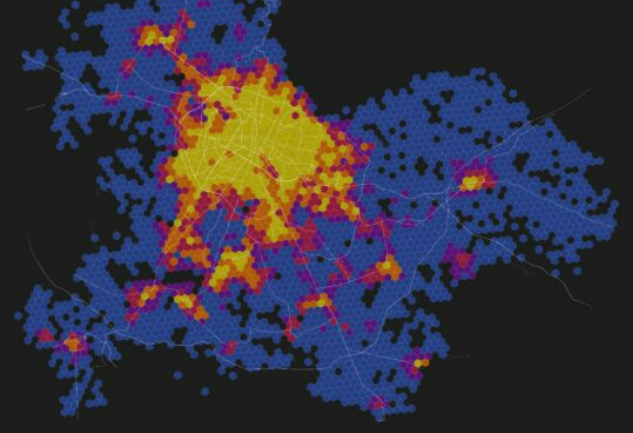

Despite being one of Mexico’s main tourist destinations, Acapulco is one of the worst cities evaluated in the Tec’s Proximity Index. This means that its population doesn’t have quick access to basic services. (Photo: Tec’s Observatory of Cities)

In recent decades, the right to adequate housing has not been fulfilled, because the closer it is to main avenues, hospitals, schools, and cultural and recreational services, the more expensive and inaccessible it is to millions of Mexicans.

Adequate housing, an unfulfilled right

The counterpart is that cheaper housing, which can be purchased with credit from INFONAVIT, is generally “located in remote areas that lack basic services, generating segregation, inequality, and security issues,” explains Alfredo Hidalgo Rasmussen, Associate Dean of Tec de Monterrey’s School of Architecture, Art, and Design (EAAD) and co-creator of the Index.

In recent months, INFONAVIT has changed its rules for granting housing loans, establishing that there must be a primary school, a supply center, and recreational areas within a two-kilometer radius. And there should be health centers and secondary schools within a 2.5-kilometer radius.

The Proximity Index developed by the Tec was created based on this perspective to include INFONAVIT’s new rules, in which people should be able to walk to these services within 15 minutes. It can therefore be a complementary tool for planning housing.

Proximity Index

The tool has been used to analyze 75 cities and metropolitan areas, with the result that Greater Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Ciudad Juárez stand out as the cities that best meet the requirements for acceptable distances to access services, while Acapulco, Mexicali, and Tlaxcala obtained the lowest rating.

This tool also verifies the actual distances that people walk to services, explains Rossana Valdivia Pallares, Executive Coordinator of the Observatory of Cities.

“We’re very interested in making sure that the measurements are linked to the reality of the people on the streets and not the maps. We check the actual infrastructure in the Index. We’ve observed that there are avenues that can’t be crossed or there are rivers that don’t have bridges in some places.”

The experts used the methodology of network science, which allowed them to examine the streets as if they were networks and make nodes from them with distances that can be measured.

They designed a programming code to calculate the shortest distance to any of the facilities (as Waze does).

After trial-and-error testing, they ran the program in 75 cities, with their respective neighborhoods, gated communities, or towns, to verify that it is an effective tool.

Valdivia Pallares says that they used databases from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) to georeference schools, pharmacies, and stores.

The topography of the sites is an element they’re considering adding to the index soon since there are zones that affect walkability, such as mountain communities.

Cities accessible to everyone

The pandemic has highlighted housing inequalities, since people had to stay at home to work and health centers were more than an hour away from their homes, when the ideal situation would be for them to arrive on foot.

Alfredo Hidalgo Rasmussen believes that this health crisis has reopened the debate about how to recover our cities from the perspective of proximity.

“It’s a wake-up call for us to go back to having cities with much more immediate surroundings that meet our needs and we therefore travel less on public transport or in private vehicles.”

He adds that the beauty of the algorithm is that it’s accessible to everyone. You don’t have to be an architect or urban planner to consult the Proximity Index, so it can also help INFONAVIT beneficiaries to decide on one home or another.