Design, architecture, and urban planning can be driving forces for creating spaces where humans can live in harmony with other species. Or at least, this is what multispecies design proposes, an emerging field that seeks to actively include the needs of animals, plants, microorganisms, and other living beings in the creation of objects and spaces.

The idea arises from an ethical crisis in these disciplines, resulting from the anthropocentrism—the view that considers humans to be the center of all things—that has dominated their practice until now.

This anthropocentric vision is also partly responsible for the environmental and ecological collapse the world is currently facing, with mass extinctions of organisms, habitat destruction, and increased pollution, so it has become urgent to rethink and redesign our way of living, building, and relating to our surroundings.

“There is a very extensive climate crisis that has caused many species to be in danger of extinction,” says David Sánchez, research professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) at Tec de Monterrey. “We are currently looking for ways to be more inclusive while causing minimal impact.”

Sánchez is part of a global group of individuals and researchers seeking to promote a new form of human existence that recognizes animals, plants, and other living beings as agents with interests, rights, and needs, raising questions such as who has the right to inhabit the spaces we design.

Recently, the Cumulus Association, a global association of higher education institutions in the fields of art, design and media, with more than 300 members from 63 countries, published its most recent statement where they consider multispecies design as a fundamental aspect to reaffirm design’s commitment to inclusivity, collaboration and innovation.

How to use multispecies design

To make theory a reality, multispecies design considers nonhuman species as clients with needs and rights that must be considered from the outset of projects. “An owl, a snake, or a tree can be a client,” says Sánchez.

Thus, constructions or interventions must be planned around the needs of the native species that inhabit a site. Naturally, this requires the collaboration of different disciplines, including biology, ecology, anthropology, geography, geology, engineering, and data science.

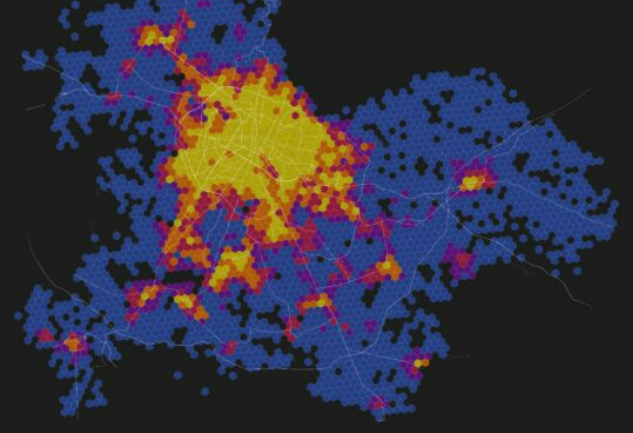

Organic materials are also used, and technologies such as camera traps and drones are integrated to map the territory and the ways animals use the space. “These tools allow us to identify how many times a fox passes by or where a bird is nesting, for example,” explains the researcher.

Another essential concept is that built systems must be extensions of the natural ecosystem that foster and support biodiversity.

An example of this was when an abandoned railway track in New York, USA, was rehabilitated to convert it into an urban park that features native vegetation, attracting birds, insects, and other wildlife.

The Living Breakwaters project in Staten Island, New York, designed a series of semi-artificial reefs made of ecological concrete and rocks, which house oysters, crustaceans, and juvenile fish.

These structures were designed to reduce wave energy, halt erosion, and restore the bay’s biodiversity. Thanks to this, wading birds, seals, snails, mussels, crabs, and several species of fish have returned to the area and use the structures.

Thus, multispecies design can be as simple as creating a light post that, in addition to generating light, serves as a nesting site for birds, or as complex as a building constructed from biomaterials that integrates the existence of multiple species.

Cases in Mexico and Latin America

In Latin America, multi-species design has begun to be implemented in projects such as the Andean-Amazonian Corridor, developed in Colombia, which facilitates connectivity between the mountainous landscapes of the Andes and the plains of the Amazon, thereby conserving species like jaguars, deer, and tapirs.

Sánchez leads the Advanced Design Processes for Sustainable Transformation research group, which is currently collaborating with the Catholic University of Chile and the University of the Andes on an initiative called Planetary Design, involving projects of this nature.

“We are creating networks of Latin American researchers to promote multispecies design in our region,” says the expert.

Recently, the group published a study as part of the Cumulus Conference 2024 that presents the state of the art in this field, as well as four practical cases created by students and professors from different Tec de Monterrey campuses.

Among them is a collaborative project between students and the CRIFFS organization to create objects designed to help injured or vulnerable wildlife, such as turtle nests or support structures for stranded cetaceans.

In the future, the group plans to develop various design projects that focus on empathy toward other living beings.

Citizen Science to Promote This Model

As a whole, multispecies design seeks to broaden the scope of traditional sustainable approaches, such as energy efficiency and carbon reduction, as many remain anthropocentric, ignoring all other species and failing to consider whether the built environment fosters or destroys nonhuman life.

It also seeks a reconnection between humans and nature, as urbanized societies have become increasingly disconnected from ecological cycles, life processes, and cohabitation with other species.

According to Sánchez, for multispecies design to truly have a positive impact on our way of life, it will be necessary to rely on citizen science. Individuals have the power to create records of the species they see passing by or those they’ve stopped seeing.

“They can show us indicators or needs, generating an alarm or indicators of what should be emphasized,” says the researcher.

This could result in public policies that provide financial and infrastructure support for construction or design projects that consider other species and regulate or prohibit those that go against them.

“Keeping a river full of biodiversity, free from pollution, completely healthy, with drinkable water, starts from there, from who reports it, how it’s protected, and what’s designed to continue caring for it,” says Sánchez.

Were you interested in this story? Want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more: marianaleonm@tec.mx