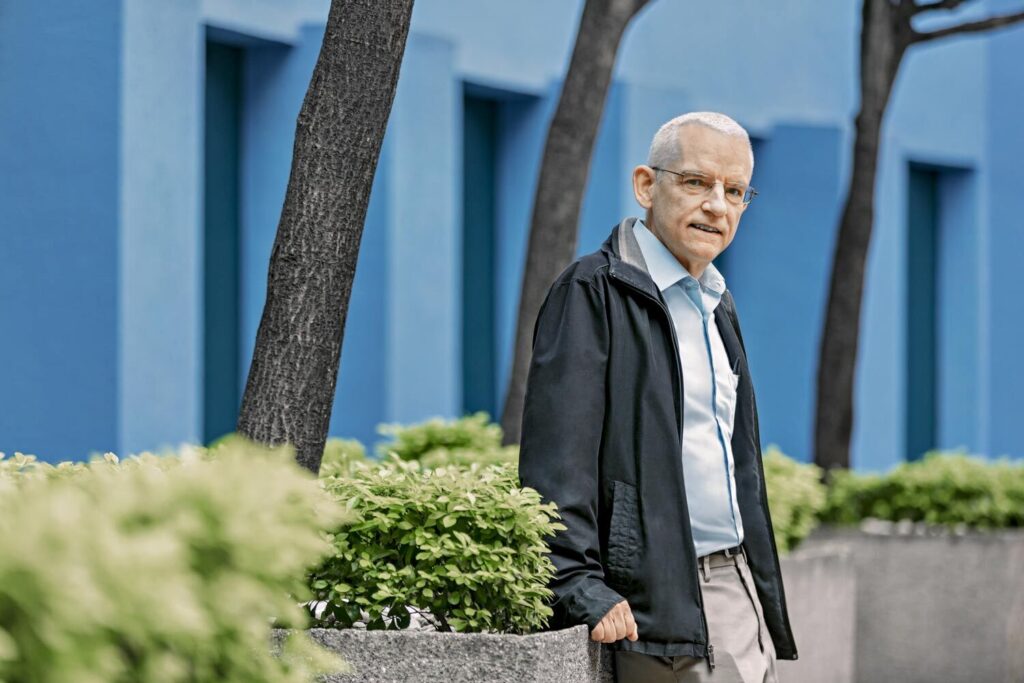

“Are we in good hands?” That’s the pressing question family businesses often face—especially during succession processes, when leadership (whether the CEO or the chairperson) or ownership is handed down from one generation to the next. It’s in these pivotal moments that trust takes center stage, reflects Justin Craig, Distinguished Professor of Family Business at the Tec de Monterrey Business School.

“If you don’t have trust, you don’t have a bloody thing. Without trust, families are not able to optimise the chance of transitioning across generations,” says the professor, who is part of Tec’s Faculty of Excellence initiative.

As a researcher, he has dedicated his work to studying family enterprises. He has authored more than 50 academic papers and written several books on the subject. Craig has also taught at the Kellogg School of Management and Bond University in Australia.

At the 2025 Global Family Business Summit—hosted by the Institute for Business Families in Mexico and Latin America (IFEM) at Tec and The STEP Project Global Consortium, held at EGADE Business School—Craig delivered a keynote titled Without Trust, There is no Transformation nor Revolution, where he broke down the concept of trust through a scientific lens.

The Four Dimensions for Measuring Trust

Craig argues that trust can—and should—be understood through a scientific lens, especially in the context of family businesses. This concept, he says, can be explored through business science and measured with academic rigor.

“As scientists, we need to say, well: What is trust, and why does it matter?” he says. “The richness of it, the importance of it, the irrelevance of it, and ultimately the science of it.”

Based on the analysis of 128 research studies on trust, scholars have found that trust isn’t just a subjective feeling. It can, in fact, be measured through four key dimensions: integrity, ability, benevolence, and consistency.

- Integrity: This means a person is honest, guided by values and principles, follows through on promises, and respects ethical standards. For example, a CEO who doesn’t lie about the company’s finances.

- Ability: Refers to the technical, professional, and interpersonal skills needed to perform a role. These competencies help leaders make effective decisions based on their expertise.

- Benevolence: This is the perception that someone acts for the greater good, with positive intentions toward others—being cooperative and altruistic. For instance, someone willing to help and bring people together to pursue a shared goal.

- Consistency: It’s about behavioral reliability—when someone reacts predictably and responds similarly in comparable situations. This creates a sense of safety and reduces uncertainty or distrust.

A Simple Tool for Evaluating Relationships

The researcher uses the four dimensions to form the acronym IABC. He sees it as an educational tool that is simple, memorable, and practical for use in both personal and organizational relationships.

Using this framework, people can pinpoint why they may not trust someone, for example, a person might be highly skilled but selfish, or a great team player who reacts unpredictably when faced with challenges.

In that sense, the dimensions can serve as a diagnostic tool to assess relationships within a business family—between siblings, cousins, or even among executives and owners. Craig presents this strategy as an easy way to identify exactly where trust begins to break down.

Showing Vulnerability to Build Trust

One powerful way to build trust within business families, Craig explains, is by showing vulnerability. A key foundation of trustworthiness lies in people’s ability to admit they don’t have all the answers. This isn’t a sign of weakness—it’s a deeply human way to foster genuine and lasting relationships.

Asking for help is one of the simplest ways to express vulnerability. When someone reaches out for support, they’re signaling a willingness to engage in open dialogue, which can break the ice and lay the groundwork for trust. Still, Craig notes, it’s not always about literally saying “help me”—vulnerability can also come through empathy, using phrases like “Can I step into your shoes for a moment?” or “Help me understand where you’re coming from.”

In a business context—where emotional ties and financial interests are often intertwined—families can benefit from showing vulnerability to resolve conflicts, bridge generational gaps, defuse tension, and prevent breakdowns in relationships. It’s not about giving up control, but rather about creating the conditions for mutual trust to grow.

“You might feel nervous about trusting others with your information and opening your home and business to newcomers. It’s understandable,” Craig says. “If we want to build trust, we need to demonstrate vulnerability and admit that we need help and walk the talk.”

Easing Trust Tensions with Action Plans

Trust tensions can arise among family members, business managers, and company owners—making it essential to have clear action plans that support generational continuity, decision-making clarity, and the overall health of the family enterprise system.

“What sort of plan do we need? A strategic plan, a family talent development plan, an asset, wealth and estate plan, and a governance plan,” Craig explains.

The business’s strategic plan aims to align the operational team with the owners’ expectations, all while keeping a long-term vision in mind and addressing key questions like, “Are we in good hands?” Meanwhile, the wealth, asset, and succession plan focuses on the effective management, distribution, and legacy of financial resources.

The third plan—family development—prepares the next generation with essential skills in leadership, finance, and governance. And finally, a governance plan outlines the structures, rules, and processes that guide decision-making. Through family councils, management boards, and ownership committees, this plan promotes transparency, institutional strength, and collective decision-making to ensure harmony across all roles.

Building Trust Between Academia and Business Families

In order for research on family businesses to have real impact, it’s essential to foster genuine, trust-based relationships between academics and business families, says Craig.

Researchers must value and learn from the families they study—seeing them as partners and “teachers” who help enrich academic work. On the flip side, approaching families solely to extract data can erode trust and damage the reputation of the academic community.

Craig emphasizes the unique value for professors in building long-term relationships with business families—following them over time and seeing them as living case studies, appreciating how they evolve from one generation to the next.

“If you build trust, you will follow these living case studies as those five-year-olds evolve into 25-year-olds on your watch,” he says. “They provide me with insights I don’t get by academic papers.”

As researchers, it’s critical to live by the IABC model—maintaining integrity, demonstrating ability, showing altruism, and being consistent—just like any other member of the family business ecosystem.

“So the more the academic can build a database of families who are all the same but different, the better they are to serve or to provide assistance to the families they build their relationship with,” Craig concludes.

Were you interested in this story? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more: marianaleonm@tec.mx