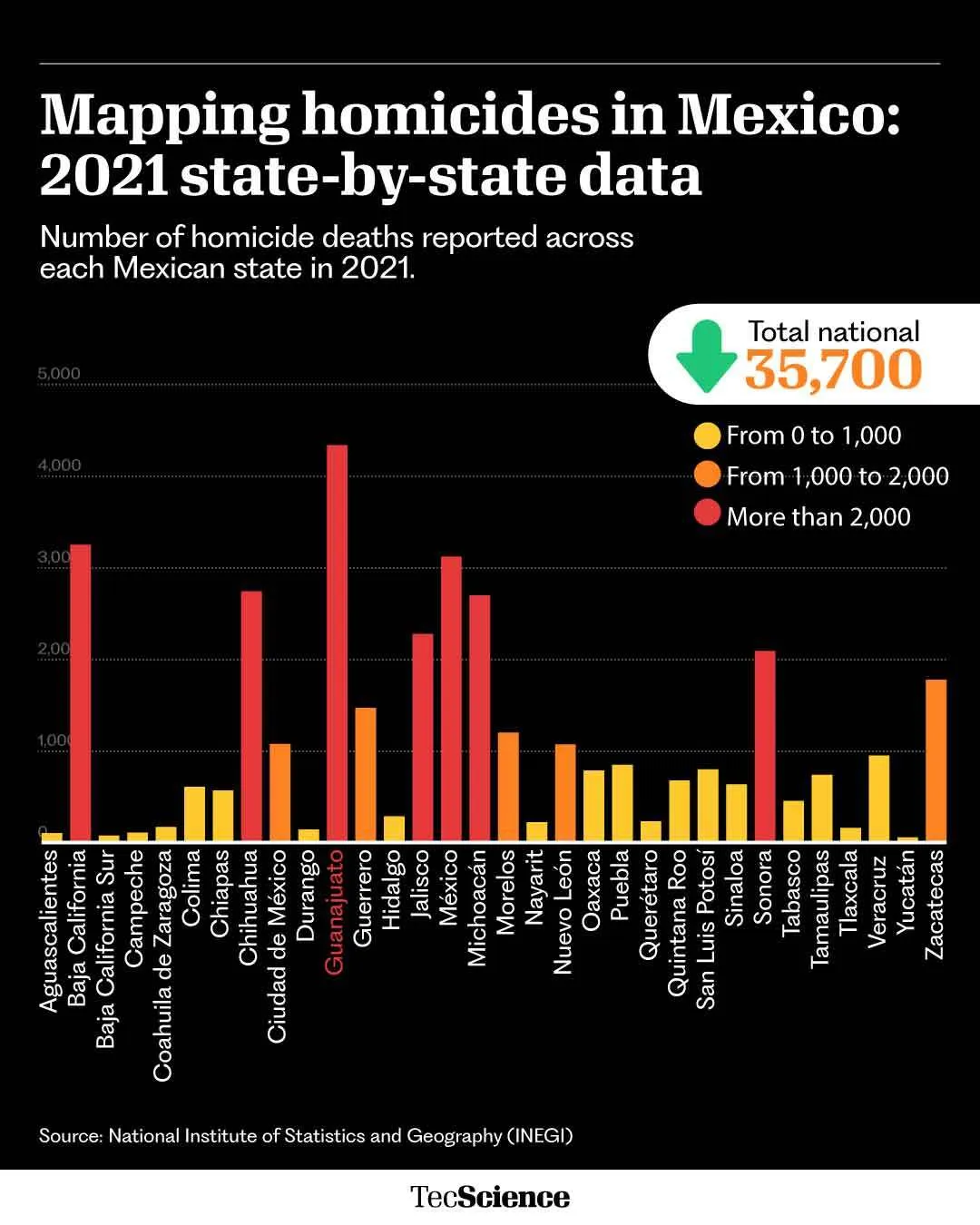

In Mexico, violence linked to organized crime is one of the most worrying public security problems and one of the issues that pains citizens the most. In light of this, researchers suggest relying on data and evidence to dismantle the economic infrastructure of these organizations as an effective strategy.

Since 2015, the country’s organized crime rate has increased by 64.2%, except for a slight decrease in 2020. Since then, homicides related to these groups have also increased from around 8,000 to more than 23,000.

Through various studies, Pedro Torres, a lawyer and retired research professor at the School of Government and Public Transformation at Tec de Monterrey, has analyzed the phenomenon and found that the main way Mexican authorities have tried to resolve the situation has been by deploying the armed forces—such as the Army and the police—and little to no efforts have been made to affect their finances.

Combined with other efforts, doing so would be an effective tactic against them, as it would complicate their operations. “These organizations have a financial, asset, and economic structure that allows them to commit crimes. However, no comprehensive public policy exists to attack this,” says Torres.

To control their finances, Mexican law provides various mechanisms for confiscating assets of illegal origin, such as money, means of transportation, and property.

“Unfortunately, within the institutional model of the prosecutor’s offices, the areas of asset and economic analysis haven’t fully taken root,” Torres explains. “We need specialists.”

Organized Crime in Mexico: How to Combat It

Today, municipal, state, and national agencies dedicated to investigating crimes invest most of their budgets and efforts in the criminal network, focusing on issues such as logistics and ballistics rather than the economic aspect.

According to the researcher, having field experts is essential to effectively combating organized crime. “For that, you don’t need criminologists or forensics, but rather accountants, economists, financiers, and data analysts,” explains Torres. “A criminal network almost always has a financial network in tandem.”

These groups mainly base their operations on money laundering and corruption of authorities, specifically during election campaigns, and both crimes can be detected through financial analysis.

By analyzing data from the financial system, authorities could see how money is moving within these criminal cells, who is buying properties, vehicles, or weapons, where they are investing it, and which bank accounts are involved. “You start recognizing transactions and tax identification numbers,” says Torres.

In countries like the United States and Italy, an effective strategy has been using opportunity criteria, a mechanism of the justice system that allows one to negotiate with a captured member of a cartel or criminal group to obtain information in exchange —known as intelligence—.

“If you help me reach the highest levels of the organization and understand the financial structure, I’ll give you certain benefits,” Torres analyzes.

However, opportunity criteria are rarely used in Mexico, and when they are, it’s almost never to gain information to dismantle the economic network. “When you look at the real numbers, the sentences, the seizures of planes or assets, you realize that we arrest many people, but nothing happens,” the researcher says.

Legal Tools to Dismantle Their Economic Structure

There have been very few convictions for money laundering, corruption, or asset seizures in the country, which allows criminals to access their assets upon release or transfer them to other members to continue their operations.

“Today, what happens is that they arrest someone and put them in jail, but their assets remain intact,” Torres argues.

In a study published in 2021, Torres, Juan Montero, Carlos Vázquez, and Sylvia García analyzed the efforts of northern border states to combat organized crime through legal tools to seize assets associated with illegal activities.

Some of these include forfeiture, extinction of domain—the recovery of assets resulting from criminal activities—and asset abandonment.

“The recovered money can and should be used by the State to continue fighting crime,” says Torres.

Through data analysis and interviews with attorneys general, prosecutors, and other members of their security systems, the study found that obstacles prevent governments from truly attacking their economic structures.

These include the lack of institutionalization of Financial and Asset Intelligence Units, the absence of standardized protocols, limited coordination between state institutions, legal obstacles, such as ambiguities in the law and weaknesses in due process, a lack of legal training, corruption, and state fragility.

“The most immediate weakness is found in the municipalities,” Torres explains. “Because they are closer, they are more likely to be co-opted through power, terror, or fear.”

In states like Baja California and Nuevo León, some progress has been made in positive efforts focused on this. Despite the challenges, these tools have great potential to help the country’s authorities successfully combat organized crime.

The Future of Fighting Organized Crime in Mexico

Despite the government’s efforts to control the situation, it’s hard to deny that the country is at a critical point of insecurity and violence at the hands of drug trafficking and other criminal organizations.

“Over time, the regions considered of concern have been increasing,” Torres explains. “A few years ago, we would never have imagined that El Bajío region would face its current problems.”

Another example of this is the recent declaration by the US government designating some Mexican cartels as foreign terrorist organizations. Although there are conflicting views about it, this could represent a significant change in the strategy to fight these crimes.

“This external control mechanism will impact the country’s public security policy,” the expert says. “They will be adding pressure and demanding results.”

For the researcher, this means that the country faces a valuable opportunity to expand the use of existing legal tools to limit the financial structure of criminal organizations and thus expedite the fight against them.

Although the methods of money laundering or committing acts of corruption may change over time with technological advances, closely monitoring the assets and economic movements of criminal organizations will always be a good strategy to combat them.

“If we analyze it, most crimes are primarily motivated by money,” says Torres. “With our studies, we provide the State with tools, through databases that it must review to focus its efforts on attacking the economic aspect.”

Were you interested in this story? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more: marianaleonm@tec.mx