Before writing The Planet of Fungi, Naief Yehya was suspicious of nature. “It’s just there to see how it destroys you,” confesses the journalist and writer, known for his critical perspective on technology, media, and culture since his first novel, Obras sanitarias (1992).

“I had spent my whole life within four technological walls,” he says. That experience led to a “great rejection of the natural world.” But when he began researching the world of fungi, his perception changed: what was once a distant relationship transformed into profound respect.

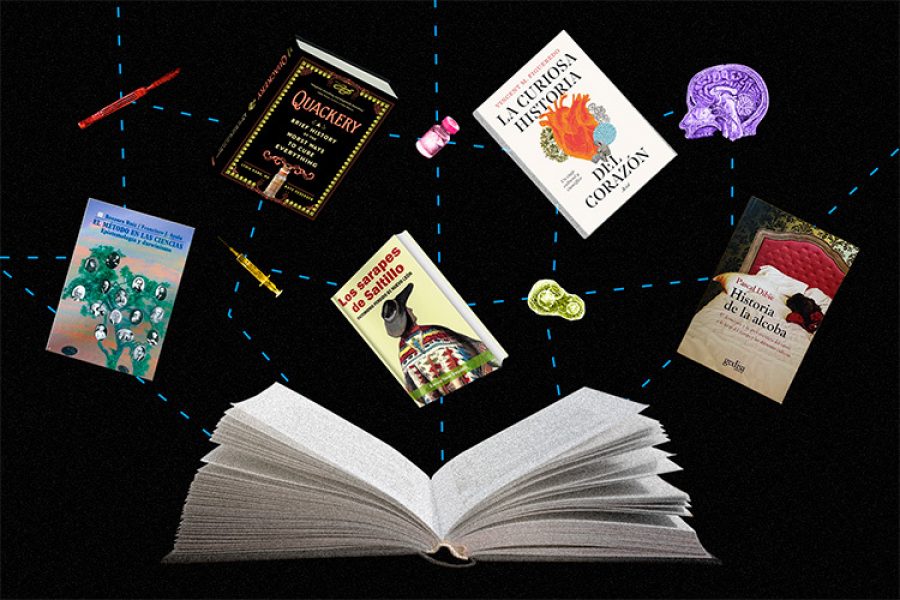

Yehya presented The Planet of Fungi at the 2025 Monterrey International Book Fair. The essay traces the history of these organisms, from their appearance millions of years ago to their role in contemporary digital culture, including the use of psychedelic substances in Silicon Valley to inspire creative and technological processes.

“We’re Living Through a Psychedelic Renaissance”

Although the history of fungi traces back thousands of years, Yehya says this is the ideal moment to tell it. “We’re in a renaissance, not just of fungi, but of all psychedelic substances, after centuries of repression. Not only by the Inquisition, but also by intelligence agencies like the CIA and the police,” he explains.

“There’s an incoming wave of use that we’re currently living through. On the one hand, psychedelics are being incorporated as productivity tools in Silicon Valley and other corporate environments; on the other, the massification of therapies and treatments that make use of them is growing. It’s a critical moment in how we relate to psychology and how we reclaim knowledge that indigenous peoples from places as diverse as Siberia, Australia, or Mexico have known for millennia.”

What was your research process for writing this book?

I’ve worked with the theme of technoculture my whole life, and I usually approach it the same way. I live in another country whose language isn’t mine; I’ve been in the United States for many years, and I always ask myself what is being said in that culture, what is being said in mine, and in what ways can I serve as a bridge.

In this case it was the same: I was interested in understanding what was being said about psychedelics and this renaissance and how that translated to the Spanish-speaking world. I’m drawn to cultural histories. I didn’t just want to transmit information but to create literature from it. I’m an essayist; mine is the literary process.

From María Sabina to Silicon Valley

In the book you travel from María Sabina to Silicon Valley. When did mushrooms become a technological tool?

When the individualized digital culture we know today began to take shape, the visionaries, engineers, and programmers seeking to build new universes turned to LSD as a source of inspiration. Every device we use today carries that psychedelic legacy. Someone once imagined the phone—and its intimate bond with us—perhaps during an LSD trip.

The algorithms we use to connect with each other, social media, and the way we consume information all bear a psychedelic imprint, whether from LSD, ketamine, or any other substance.

The fungi kingdom was officially recognized in 1969. How did that change our understanding of mushrooms?

In the mainstream, this shift took time. We’re only now beginning to grasp its importance. It’s a biological revolution: fungi are neither plants nor animals but something completely different.

You begin to understand that there would be no planet without them. That’s why the book is titled like it is. There would be no other way for life to exist. Life would have such a different permanence were it not for the fungal kingdom.

Imagine: if it weren’t for fungi, we would live among mountains of dead matter that would never decompose. They are the planet’s great recyclers. The connections they establish and the networks they form allow forests and jungles to exist. Every breath we take contains millions of spores; we live immersed in their universe and are only just passing through.

Mycelium: The Internet of the Forest

In the book you explain mycelium as a living network. How does this tissue work among fungi?

Mycelium is this intelligent, almost conscious network that can move around and explore. It’s a living organism that moves in different directions. Unlike a root, which grows in one direction and cannot go backward because once a plant invests in finding water or nutrients in a particular spot, there’s no going back. Mycelium can change its mind. It can be capricious in its search and also has an incredible capacity to communicate.

Particularly, mycorrhizal mycelium forms connections with plants and trees, creating what many call the “wood wide web,” the internet of the forest. Through it, the fungus approaches a tree and, in a way, asks, “What do you need?” It cannot produce its own food like plants, but it can offer other things in return.

During this exchange of inputs, products, substances, and even information, fungi have been shown to maintain a form of language. When we see a fungus grow, the visible mushroom that suddenly appears, we’re actually witnessing the manifestation of that subterranean organism. These vessels, thinner than a strand of hair, circulate water and other substances that inflate the mushroom, like a balloon. It’s the visible part of something vaster.

The fungus has its aesthetic value, even its intimidating aura, because there are thousands of species with very different shapes. Every time we walk through a forest, we are stepping on mycelium. Wherever there is soil, it is there: growing, communicating, and sustaining life.

Why Do Fungi Produce Psychedelics?

You mention that we still don’t know what the fungus gains by producing psilocybin, the substance that gives it psychedelic properties. Why is that question so important?

Because it remains one of biology’s great mysteries. Why does such an ancient organism continue to invest energy in producing a psychedelic substance that requires so much effort?

The mushroom has very little psilocybin in its mycelium. It appears mainly in the fruiting body. We don’t know if it produces it to attract, to repel, or to modify its environment. The day we understand why it does this, we’ll be closer to understanding the mushroom and ourselves, to understanding nature and the relationships that sustain us.

What would you like readers to take away from this book?

I would like to see a shift in their perception of the organisms that accompany us, to leave anthropocentrism behind. All the damage to the planet comes from our human narcissism, from seeing other species as resources rather than relationships.

Science—and especially technology—has long focused on exploiting rather than coexisting. By understanding our relationship with fungi, Yehya suggests, we may finally learn to coexist with all forms of life, not just dominate them.with fungi, we’ll be able to understand ourselves better alongside all other organisms.

Were you interested in this story? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more: marianaleonm@tec.mx