On June 26th, 2000, Bill Clinton announced from the White House that the first draft of the human genome sequence was available, and the world continued to investigate. However, the banks where the information is deposited have little data on Latin Americans and even less on the Mexican genome.

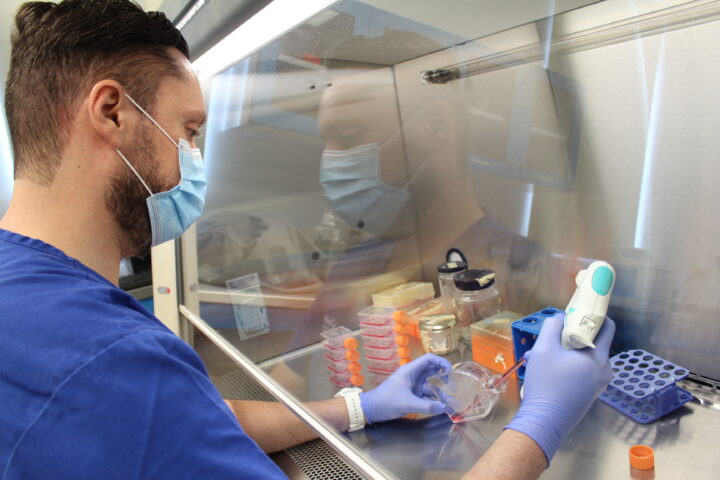

During Tecnológico de Monterrey’s first Genomics in Health Conference, TecSalud launched the oriGen Project, an initiative that will study the DNA of 100,000 Mexicans.

At the gathering, 10 well-known genomics and healthcare thought leaders explained the benefits of this research.

They agreed that opening up and sharing genomic data will be an essential component to advancing precision medicine, wellness science, and disease prevention.

A databank for understanding the Mexican genome

The human genome is unique to each individual but understanding general health data enables advances in preventive medicine.

Esteban Parra, Director of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto, said that some populations, such as the Mexican one, have poor genetic representation.

“There is a geographic imbalance and fixing this bias will give access to more diversity with greater detail, which will provide researchers with more evidence,” he said.

Rolando González, head of Poblar, an initiative aiming to put together the genetic map of Argentina, told at the Conference that “Latin American populations have a special background. These genetic variants are associated with populations that we know.”

The study of genetic data consists of two parts: the genome and the phenome, a reflection of the individual’s lifestyle and other variables such as the environment.

Adding these together allows us to map the genetic risk of a population and prevent chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and cancer in a timely manner.

Meanwhile, the oriGen Project will enable us to address the lack of data on the Mexican population and is an important window into personalized medicine.

“It’s very important to have data from different biographies, because the information acquired in one doesn’t apply in another,” explained Josep M. Mercader, a research scientist at the Broad Institute, an organization from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard that researches genomic medicine.

The information collected will require data science to store and interpret it correctly.

Wellness and prevention science

The human genome can go further. With artificial intelligence (AI), it’s possible to predict and prevent chronic diseases.

“Wellness and prevention science can prevent and reverse disease, including aging,” said Leroy Hood, Co-Founder of the Institute for Systems Biology (ISB) and Chief Scientific Officer at Providence, a non-profit health system.

Hood is certain that healthy aging is possible, but “these types of projects require mass data and artificial intelligence.”

The researcher and his team have collected data from one million people and, with artificial intelligence, intend to address the five major challenges to modern medicine:

- Quality

- Cost (saving on critical diseases)

- Rapid population aging

- The chronic disease explosion

- Opened biobanks for everyone

A resource for everyone

Carlos Bustamante, CEO of biotechnology company Galatea Bio, started his speech by asking, “How do we offer precision health to all?”

The expert said that “genetic data is more valuable than all the oil in the world” and that he hopes to create a biobank of all America with more than 10 million genomes by 2025.

Bustamante’s vision is to give individuals and families control of their digital health data so they can find out how it is used, by whom, and for what purpose.

“Artificial intelligence isn’t enough for this. A multidisciplinary team is also required to mine the data,” he said.

According to Dr. Bustamante, we need to decentralize information. He recommends opening up the data to everyone, something as simple as having it on your cellphone and being able to consult and use it to your benefit.

Iscia Lopes Cendes, head of the Molecular Genetics Laboratory at the Department of Medical Genetics in the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the University of Campinas in Brazil, explained that the challenge is integrating the information.

Lopes is part of the Brazilian Initiative on Precision Medicine (BIPMed), and her job is to create data acquisition protocols between populations with genetic similarities.

She said that sharing genetic data is contributing to precision medicine and accelerating the progress in human health.