All organ donations are made voluntarily, but they cover only 10% of the global need, which is why xenotransplantation has brought new hope.

As gene editing brings us closer to such a possibility, it’s important to know what it is and what bioethical issues it presents.

What is Xenotransplantation?

Xenotransplantation involves transferring cells, tissues, or organs from animals to humans. For 300 years this procedure was something that only existed in the imagination. The first documented attempts included blood transfusions and frog-skin grafts.

In the 1960s, French and American scientists attempted, unsuccessfully, to use chimpanzee and baboon hearts and kidneys as replacements for diseased organs in humans.

Over time, the genome sequencing of thousands of species has revived these ideas. DNA sequencing has brought pigs to the fore.

The reproductive maturity of these animals, their gestation period, and the size of their organs has qualified them as the best candidates for these procedures. Another significant step was the human experience of exploiting them for meat production, something that seems to translate into unlimited access to organs.

Pig Heart Transplant

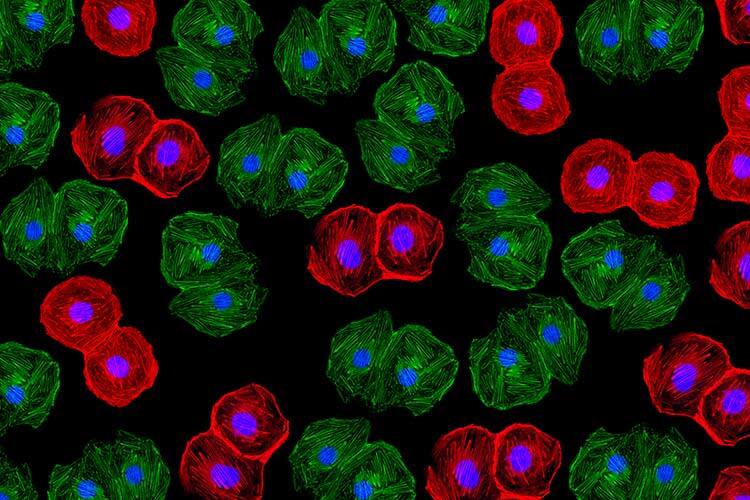

The biggest boost to xenotransplantation research has been gene-editing technology, particularly CRISPR-Cas9, which works like molecular scissors to cut DNA precisely.

Thus far, the viability of modified organs has been tested in brain-dead patients, but it has been unsuccessful in the long term. The furthest it’s been reached are two clinical trials at the University of Maryland; the patients were David Bennett and Lawrence Faucette, one of whom survived with a pig heart for two months and the other for six weeks.

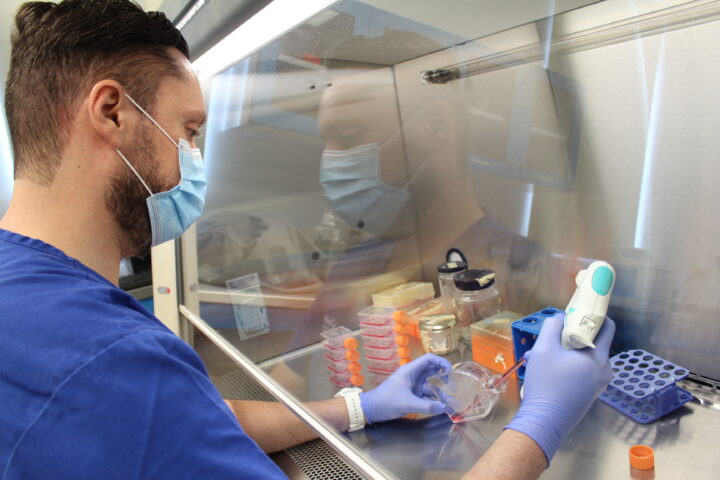

In Argentina, Laura Ratner from the Animal Biotechnology Laboratory (LabBA) at the University of Buenos Aires, is part of the first group in Latin America to achieve a litter of genetically modified pigs. Although the genes responsible for hyperacute rejection have been removed from the piglets, other genes that would enhance their compatibility with humans need to be inserted.

Research groups working with xenotransplantation still have a long way to go in order to come up with a safe solution. Pending tasks include overcoming long-term immunological rejection, preventing the transmission of diseases, and developing bioethical protocols that guarantee that a decades-long dream is achieved under optimal conditions.

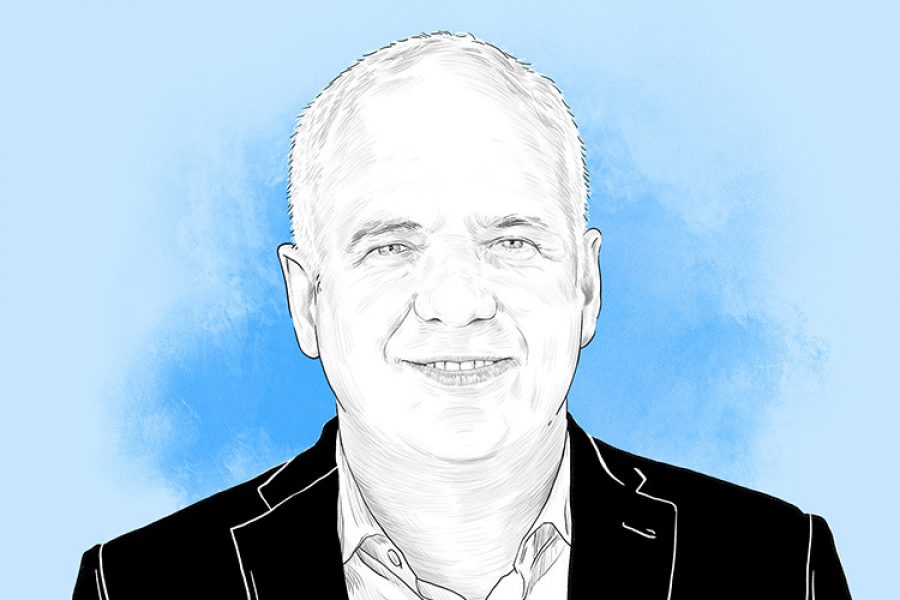

Man Who Received Pig Kidney Marks a Milestone

A 62-year-old man with end-stage kidney failure became the first human to receive a genetically-edited pig kidney, announced doctors from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, United States, on March 28.

The transplant operation, which lasted four hours and was performed on March 16, marks a major milestone in the quest to provide more readily available organs to patients, the hospital said in a statement.

The patient, Richard Slayman of Weymouth, Massachusetts, recovered well and was discharged April 3, the hospital said. Unfortunately, on May 11th his decease was reported by his family although the doctors said that they had no indication that his “sudden passing” was the result of his recent transplant.

Slayman had received a transplant of a human kidney at the same hospital in 2018 after seven years on dialysis, but the organ failed after five years and he had resumed dialysis treatments.

The pig kidney was provided by eGenesis, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, from a pig that had been genetically edited to remove genes that could be harmful to a human recipient and add other human genes to improve compatibility. This company also deactivated certain viruses inherent to pigs that are able to infect humans.

Kidneys from similarly edited pigs raised by eGenesis had successfully been transplanted into monkeys that were kept alive for an average of 176 days, and in one case for more than two years, researchers reported in October in the journal Nature.

Drugs used to help prevent rejection of the organ by the patient’s immune system included an experimental antibody treatment called Tegoprubart, developed by Eledon Pharmaceuticals.

The pig kidney procedure brings the field of xenotransplantation closer to a possible solution regarding the global organ shortage.

According to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), more than 100,000 people in the United States await an organ for transplant and kidneys are the most common organ needed for transplants. (With information from Reuters)