According to the first study of its kind conducted in the country, nine out of ten Mexican adults experienced at least one adverse event during their first eight years of life (ACEs, for Adverse Childhood Experiences). The research was carried out by the Early Childhood Center at Tec de Monterrey and the FEMSA Foundation.

The study gathered data from 1,448 adults and 200 children.

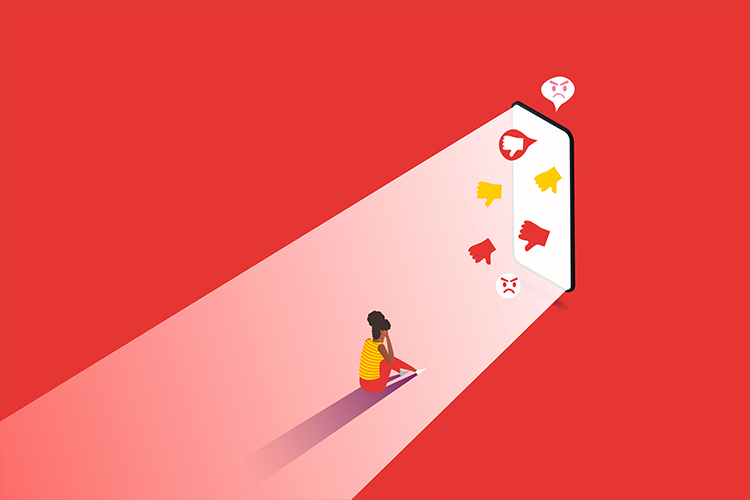

ACEs are stressful or traumatic events that, without the proper support, can affect a child’s development—not only in their early years but throughout their entire life. Today, at least 10 categories of adverse experiences during early childhood (from birth to age eight) are recognized:

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Physical neglect: when children are not provided with healthy food at appropriate times or their hygiene is neglected.

- Emotional neglect: when caregivers fail to help children manage different levels of stress.

- Living with someone who has a mental illness or suicidal thoughts.

- Having a family member with a drug or alcohol addiction.

- Witnessing domestic violence.

- Death of a parent or parental abandonment due to divorce.

- The imprisonment of a family member.

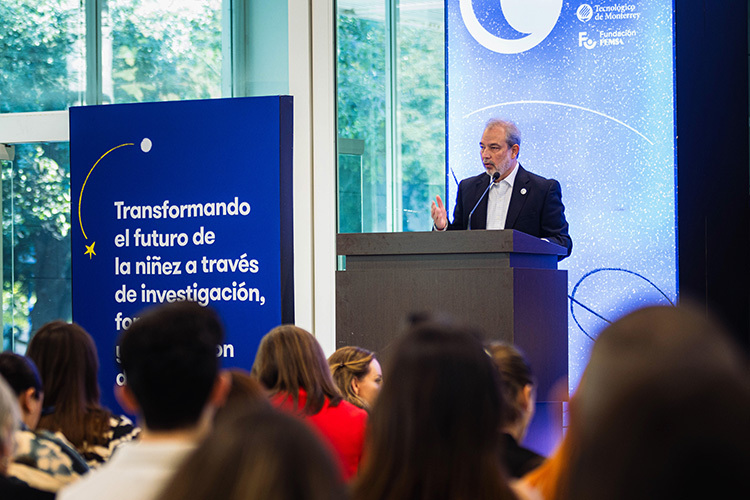

Manuel Pérez, director of the Center, presented the results of the Panorama of Adversity in Mexico, a national survey on ACEs. The survey included men and women over the age of 18, residents of urban and rural areas, and caregivers of children between the ages of three and five.

The findings also show that experiencing four or more ACEs can significantly impact childhood development and increase the risk of developing both physical and mental health issues, such as obesity, hypertension, depression, or anxiety. “It’s impossible to discuss early childhood without addressing adversity,” Pérez stated.

The initiative was unveiled during the Second International Early Childhood Forum, where other findings and research conducted by the Center were also presented.

Adverse Childhood Experiences in Mexico

Among the data gathered by researchers from the Center, the following results stand out:

- 9 out of 10 Mexican adults experienced at least one ACE.

- 1 in 3 experienced parental absence.

- 3 in 10 were exposed to substance abuse or domestic violence.

- Nearly 2 in 10 suffered sexual abuse.

- 6 in 10 experienced physical neglect.

- 22.6% experienced more than 4 ACEs.

- 4 in 10 children had experienced at least one adverse event (based on data from caregivers).

The study also reveals that 22% of respondents experienced emotional neglect, 14% had separated or absent parents, and 10% faced domestic violence.

“These percentages reflect dysfunction in families and homes—they speak to abandonment or inadequate care,” said Pérez. “These results raise many more questions that, to answer them, our research team will need to conduct additional studies.”

He added that this work highlights the urgent need in Mexico and globally to adopt new methodologies to understand this issue better and contribute valuable information for designing effective policies and interventions for early childhood.

For example, the adverse effects of ACEs can be counteracted or mitigated through positive or benevolent experiences.

The director emphasized that it is the responsibility of the community, scholars, researchers, and those working in early childhood and as global citizens to create a better, more sustainable, responsible, and equitable society with the best possible caregiving environments for children worldwide.

Benevolent Experiences to Combat Adversity

Julieta Rodríguez, leader of the Developmental Biology and Well-Being in Childhood Research Group, stated that benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) can counteract the risk of developing physical and mental health issues due to ACEs.

“The effects of adversity can also be mitigated, meaning that not every person who has experienced traumatic events in childhood will necessarily experience negative effects on their physical or mental health,” Rodríguez explained during the study presentation.

Just as 10 ACEs have been established and studied globally, the same is true for benevolent experiences, and there is a widely recognized scale for them.

These experiences include:

- Emotional support from caregivers: Having at least one adult who offers love and attention.

- Positive school environment: Feeling good at school, with teachers who care and friendly classmates, in an environment that encourages a love of learning and effective socialization.

- Stability and routine: Having a daily routine at home that provides a sense of security and predictability.

- Opportunities to play: Access to play and recreational activities, where play is a fundamental tool for learning and social development.

- Meaningful friendships: Having at least one good friend can increase a child’s resilience and provide an additional support.

The study conducted by the Early Childhood Center found that 49.7% of respondents reported having 9 to 10 BCEs, 29.6% had between 7 and 8, and 13.4% had between 5 and 6. Additionally, it was found that those who experienced a higher number of BCEs showed a reduction in the prevalence of adverse health conditions, such as obesity, hypertension, and mental health disorders.

“We also measured these benevolent experiences and looked at their association with the risk of experiencing adversity or physical or mental health issues. We found that benevolence has a cumulative effect; we saw that having nine to ten benevolent experiences reduces the risk of physical and mental illnesses—it’s almost like a protective effect,” said Julieta.

However, the study also reveals that participants from rural areas reported fewer positive experiences than those from urban areas.

Fabiola Castorena, a research professor from the group, explained that the team used biological measurements to gain a more precise understanding of the effects of ACEs on children as part of the study.

“We took mostly non-invasive samples, such as hair, plasma, saliva, stool, and urine, which can accumulate various toxic substances, including biomarkers like cortisol and inflammatory markers in plasma,” she explained.

They can measure the microbiota in saliva and detect other biomarkers related to environmental exposure and associated with stressors in urine.

Biomarkers are molecules that change in response to stimuli. This study aims to understand whether a person exposed to a stressor might show alterations in different systems, such as the neurological or immune system.

The researchers have already collected biological data related to biomarkers and are looking to identify one with sufficient qualities to be linked to the adversity experienced by children.

A Pioneering Study

Eva Fernández, Director of Social Impact at FEMSA, stated that this study is pioneering in Mexico and was supported by researchers from allied universities of Tecnológico de Monterrey through the La Tríada initiative, which had previously conducted similar research.

This partnership, established in August 2018, with the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC) and the Universidad de los Andes in Colombia, aims to improve living conditions in Latin America, fight poverty and inequality, and work toward a more prosperous future.

In 2021, the CUIDA Center, born from a collaboration between PUC and the Fundación Para la Confianza, developed the first national survey on early adversities in Chile—the first such study in the region.

Through its collaboration with Tecnológico de Monterrey and over two years, the center shared its strategy and trained staff to adapt the survey to Mexico.

“We can’t change what we can’t see, and if we don’t have information on childhood adversity, we can’t make decisions or understand the mechanisms through which some of the health risks are transmitted, nor can we fully prepare ourselves to live a healthy and fulfilling life,” Fernández commented.

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx