Street harassment is one of the main ways in which women experience gender-based violence. Particularly, because it happens in public spaces, it has the power to change the way we inhabit the city. However, despite it being a common experience among us, research on the subject is scarce.

“We all experience it, our friends, mothers, sisters, you and I know that it happens, but there is almost nothing on record,” says Aleksandra Krstikj, research professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) at Tec de Monterrey.

In Mexico, 45.6% of women have been assaulted in public spaces at least once in their lives, according to the National Survey on the Dynamics of Relationships in Households 2021, by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI).

Given the lack of scientific evidence of this type of harassment, a group of researchers from the EAAD conducted a study on the impact of it on the daily life of a group of women from Riberas del Bravo, one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, a northern Mexican state.

In general, street harassment is defined as a series of unwanted actions, gestures, words and manifestations of a sexual nature that are directed towards women by men in public spaces.

According to academics, the effect of this is to nullify women as subjects of rights, placing them as sexual objects through humiliation and fear.

“It is a very strong control mechanism, one more way of controlling our bodies,” says Krstikj. “In the end, you are the one who has to change the way you move, where you look, how you dress or the streets you are going to walk by.”

Studying the Streets of Riberas del Bravo, Chihuahua

Led by Hugo Martínez, a researcher from the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez (UACJ) who did his postdoctoral stay at the EAAD, the experts interviewed seven women from the area to understand the times, places and ways in which they experience street harassment, as well as the way it modifies their relationship with the streets and spaces they transit.

The women, between the ages of 17 and 35, reported experiencing street harassment frequently in the form of catcalls, sexual comments, stalking, staring and men taking photos of them without their consent.

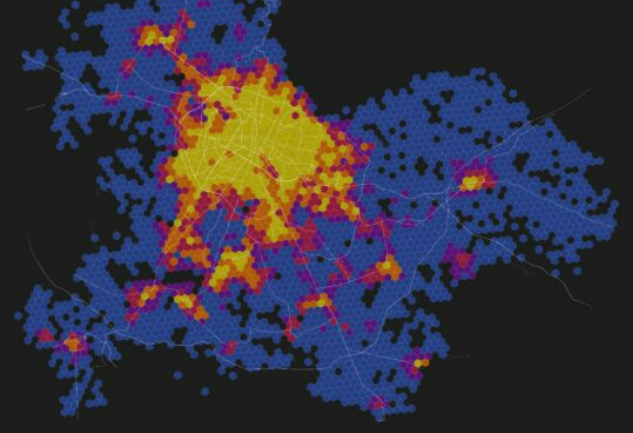

As for the spaces where these incidents occurred, they were the main avenue of Riberas del Bravo, the gas station, the market, convenience stores and empty streets.

“We saw that these events have temporality, not just spatiality, they occur at a certain time and on a certain day,” says Krstikj.

According to their results, this harassment is more frequent starting on Thursday night and lasts for a large part of the weekend, between the afternoon and evening. From Monday to Wednesday it practically disappears, with Thursday, Saturday and Sunday being the most common days.

“Every Thursday, factory workers get payed, so alcohol and drug consumption increases significantly,” says the expert about related factors.

As for who carries out this type of violence, it is men –who are generally alone or in groups of two or more– who approach them when they are alone walking to their homes, workplaces or to meet someone.

These findings echo the current situation regarding gender violence in Mexico and, in particular, in Riberas del Bravo, the fourth most lethal residential area for women in Ciudad Juárez, with 36 cases of female homicide and femicide in 2023.

Street Harassment Changes the Way Women Inhabit Spaces

Street harassment in Riberas del Bravo has a profound effect on the lives of the women who experience it.

Because of it, they tend to walk faster, grab their phone, smile and say good afternoon, avoid eye contact and confrontation. They also stop frequenting the spaces where they have experienced it and stay home at night.

This changes in the way they walk the streets is a form of social and spatial segregation, where the use that will be given to the space will depend on the persons’ gender.

Not leaving home at certain times is like a self-imposed gender curfew to avoid being harassed.

“It is the result of the entire patriarchal mechanism that unfortunately is also installed in public policies,” says Krstikj.

The researcher indicates that harassment incidents are not usually reported by women to the authorities, so it is difficult to know exactly how serious the problem is at a national level.

“The women we interviewed do not report it because they are more afraid of the police than of the men who harass them,” says the expert. According to her, in this way the State fails women by not guaranteeing safe spaces or protection mechanisms.

Urban Design Plays an Important Role in Security

Following this study, the researchers hope that other research groups will conduct new analyses with the aim of understanding street harassment and its impact on the lives of Mexican and Latin American women.

Their group seeks to propose strategies for designing public spaces with a gender perspective, in order to help reduce the frequency of this type of harassment.

“This patriarchal structure is also reflected in how cities are designed,” says Krstikj. “In an upcoming study, we will see what elements of urban design we can improve so that women feel safe.”

Some of the aspects that can be worked on include public lighting to reduce dark spaces where harassment can go unnoticed. Also, eliminating blind walls or very tall vegetation, so as not to create hiding places or barriers that make citizen surveillance difficult.

Expanding the types of activities in different localities can also be a good strategy to increase the flow of people and thus reduce incidents.

However, according to the expert, these are only elements that can help reduce the incidence of sexual harassment, because in order to eradicate it, there must be public policies focused on gender inequalities.

“Improving public spaces is like putting a band-aid on a wound, we do want to improve urban design in terms of security, but beyond that, I think we also have to influence public policies,” says Krstikj.

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx