At her desk in her pediatric cardiology office at TecSalud in Monterrey, Cecilia Britton Robles sits between a pile of colorful toys and a framed sculpture of a heart hanging on the wall behind her. Her patients know her as “Doctora Juguetes” (Dr. Toys in English), partly because the simple gesture of bringing a small toy to her patients at every appointment is one example of clinical empathy.

For her, it’s an act that transforms a potentially frightening medical visit into a moment of joy. This practice was inspired by her own childhood experiences with her pediatrician who always brought her a toy before an examination. It also exemplifies a growing focus in medicine: the crucial role of clinical empathy.

While doctors knew empathy in their day-to-day practice was important, there was no clear way to define or measure it in clinical settings. Twenty-five years ago, at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, researchers identified a significant gap in modern medical practice.

Mohammadreza Hojat, a research professor of psychiatry and human behavior, recognized that the common understanding of empathy in a person’s day-to-day life doesn’t fit into a clinical setting. “When I see a sad movie, I feel sad. That doesn’t have any relevance to patient care,” he says, explaining how existing models of empathy failed to address the unique dynamics of patient care. “But it’s relevant when we ask something like ‘is it important to pay attention to the patient’s problems?”

As Hojat explained, clinical empathy is defined by its context. It’s relevant when you’re specifically talking about health professions and practitioners interacting with patients.

Defining the Jefferson Scale of Empathy

The lack of formal definitions and measurements of this clinical skill led Hojat and his team to develop the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. It’s now been translated into more than 80 languages and used worldwide to measure and develop this crucial skill in healthcare providers.

The scale identifies three key components: perspective-taking, compassionate care, and standing in the patient’s shoes. But these clinical terms come alive in the daily practice of physicians like Britton, who demonstrates how empathy can shape a patient’s recovery and physical results.

Five years ago, Britton met Jesús Francisco García, a patient who had been living with a congenital heart condition since childhood that caused him to repeatedly visit the emergency room. Now in his 30’s, he was repeatedly visiting the emergency room convinced he was dying.

His physical symptoms were real—chest pain, and panic attacks—but his heart tests consistently came back normal. Where others might have dismissed his concerns, Britton recognized something deeper: a patient haunted by childhood memories of heart surgery and the uncertainty of living with a chronic condition.

“When there’s something wrong, the heart is very gossipy,” she says, explaining how she could differentiate between physical and emotional distress. “It doesn’t just make you feel bad. It changes many parameters, changes the electrocardiogram, changes heart function, raises certain biomarkers in the blood.” All of these were normal in García’s case.

Although Britton’s speciality is paediatric cardiology, he decided to treat Jesus Francisco, even though he was 30 at the time. Instead of simply telling him that there was nothing wrong, simply telling him nothing was wrong, she built trust gradually, explaining each test result, acknowledging his fears while helping him understand the difference between anxiety and cardiac symptoms. Over time, she guided him toward better self-care practices—improved nutrition, hydration, exercise—while remaining accessible when panic struck.

This approach reflects what researchers at Jefferson have found: clinical empathy isn’t just about being compassionate—it directly impacts patient outcomes. One study on diabetic patients by Hojat and his team showed that those treated by physicians scoring higher on the Jefferson Scale had better disease control and fewer hospitalizations.

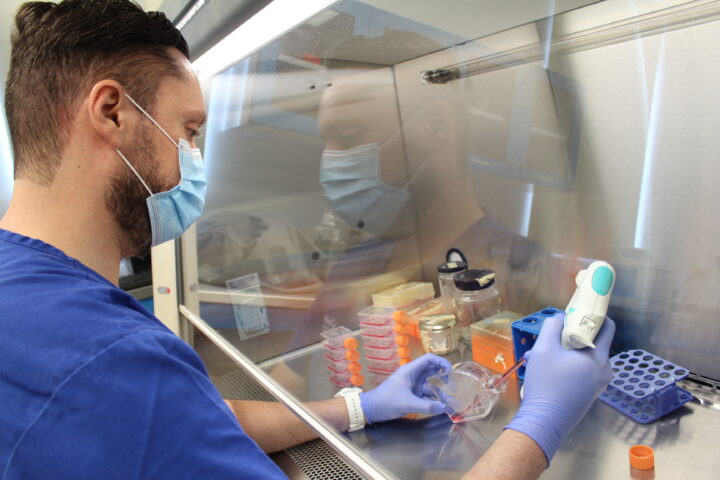

In Jesús García’s case, Britton analysed the possibility of implanting a self-expanding Venus P-Valve, which is used in cases of pulmonary insufficiency, to prevent blood going to the lungs from flowing back to the heart. The procedure was a milestone as it was the first time it was performed in Mexico.

“To Be Able to Give, You Have to be Well”

However, maintaining this level of empathy isn’t always easy. Research has shown that empathy often declines as medical students progress from preclinical to clinical training—precisely when they begin interacting with patients. “That was very surprising for us,” Dr. Hojat notes, “because that is the time that empathy is most needed.”

Some argue that too much empathy can lead to burnout, but Hojat disagrees, drawing a crucial distinction: “If you sympathize too much with the patient or with anybody else, you get immediate burnout yourself. You have to stand in the patient’s shoes but never forget that this is not your relationship as standard.”

Britton echoes this sentiment, emphasizing the importance of self-care in maintaining empathy. “To be able to give, you have to be well,” she reflects. “When I’m stressed, rushed, tired, it’s very difficult for me to examine a child, for example, because they perceive that, they feel it. When you’re relaxed and you arrive and joke and make that moment warmer, children open up.”

A.I. and The Future of Empathy in Medicine

The future of medicine brings new challenges to clinical empathy. With the rise of artificial intelligence and online symptom checkers, there’s a risk of further distancing providers from patients. But as Britton notes, “Nothing will replace this human part of medicine.”

This human element is particularly evident in how both doctors approach difficult conversations. Britton has evolved from shielding young patients from hard truths to having age-appropriate but honest discussions about their treatment. “We underestimate children,” she says. “The more transparent and direct we are at their level, the better they process it.”

As medical education continues to evolve, there’s growing recognition that technical excellence alone isn’t enough. A doctor without empathy, as Britton says, “suffers from the worst of cardiac ailments.” The challenge now is to nurture this quality alongside clinical skills, understanding that the best medical care comes from combining scientific knowledge with genuine human connection.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx