Planning an equitable city that includes people of all ages, genders, abilities, socioeconomic statuses, and beliefs is increasingly important globally; however, achieving this is a challenge that involves several factors that are not always considered in urban planning.

How we experience the cities we inhabit can be completely different depending on who we are. Therefore, creating equitable urban centers is essential given that there is a relationship between the place where we live and our health, both mental and physical.

“Sometimes, injustices can almost seem invisible if we don’t experience them,” says Ryan Anders Whitney, research professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) at Tec de Monterrey, in an interview with TecScience.

These inequalities can be observed in mobility, safety, affordability, access to water, energy, green spaces, and healthy food.

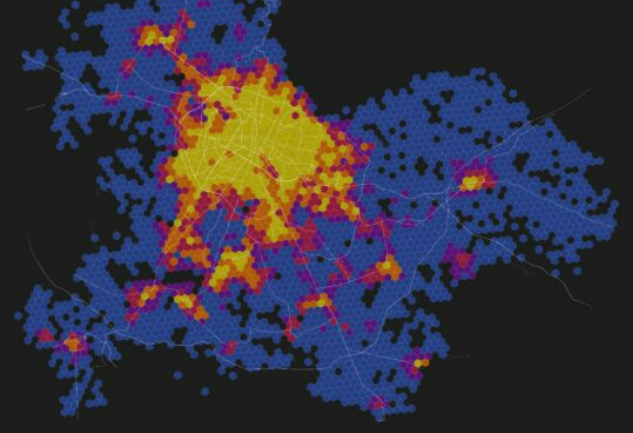

Historically, poor and marginalized areas have experienced more deficiencies around the world. In Mexico City, for example, the areas with the most access to green spaces tend to be wealthier.

To build equitable cities, architects and urban planners have questioned what factors need to be considered, finding that listening to the voices of those who experience these inequalities is key.

From time to time, you may have public policies about the importance of creating equitable, healthy and livable cities, but these are not always translated into actions.

“When we actually go out into the city, we (the citizens) experience an extreme disconnect between what these policies say and the reality of how equitable our cities are,” says Whitney.

How Can We Plan and Build an Equitable City?

Although there is no perfect formula, according to the researcher there are three major aspects that need to be covered to achieve success when planning and building equitable cities: indicators, long-term government commitment, and citizen participation.

Starting from the obvious –that we need public policies, social programs and ideas that move towards that goal– there must be indicators to measure their results and monitor whether they are working or not.

“We need to have transparent data, both quantitative and qualitative, to measure progress,” says Whitney. This also makes it easier for society to demand accountability from authorities.

The government’s long-term commitment to equity in cities is also essential. In Mexico, as in many other countries, when the current administration changes, many programs focused on reducing inequalities become unfunded or are abandoned.

For this reason, long-term projects that are strategically connected with others and have political continuity -and remain independent of who is in charge-must be carried out.

The third aspect, and one of the most important ones, is people’s participation: “We need to have collective citizen voices demanding these changes and that continue to be loud over the long term,” says Whitney.

Fortunately, nowadays, there are more conversations about the importance of creating equitable cities, both in academic circles and in society at large. An example is the active discussion surrounding the gentrification that Mexico City is experiencing.

Best Practices Are Not Always Helpful For Communities

For architects and urban planners to truly help create equitable cities, it is important that projects are contextualized to the local community.

In 2022, the expert published an article in which he seeks to discuss and visibilize the dynamics that usually occur when conceptualizing an urban development project, using Mexico City as an example.

Sometimes, techniques or methodologies –known as best practices– that are the result of an international consensus and are linked to global discourses are used, but they do not necessarily reflect the needs of the communities.

Furthermore, ideas about what cities should be like can be influenced by the social position, education level, academic networks, and privileges of project proponents: “In that process [of using best practices] we often lose a lot of the connection with people who are actually in need of something specific from their city,” says Anders.

An example of this is the case of La Araña, a neighborhood in Mexico City that is located between steep ravines and where escalators were installed a few years ago to help people move between them.

This idea was based on the successful case of Comuna Trece in Medellín, Colombia, where this type of stairs were installed, improving citizen mobility. However, when it was implemented in this Mexican community, locals didn’t use them at all.

“[The stairs] were implemented in a way that was completely disconnected from the reality of what people need, but it was symbolically important [to the government] because it represented social urbanism,” Whitney says.

How to Close the Gap Between ‘Best Practices’ and Reality?

To avoid this disconnection between an idea and reality, Whitney proposes including local voices in project conceptualization and incorporating quantitative and qualitative data to justify citizen needs.

This could be done by interviewing locals to find out what they are missing, creating diverse advisory boards that represent different groups’ interests, and building long-term relationships between planners and communities.

An example of what this could look like is a project developed by Whitney and Trudy Ledsham to create cycling infrastructure in Toronto’s schools. In this project, they collaborated with a local animator who represented the community’s voices.

Also, it would be ideal for urban development projects to have enough freedom to make changes if it turns out that the proposed idea is not the best solution.

“The whole structure of how we design urban planning is often not done in a way that allows us to be flexible enough to respond to their needs,” says Whitney.

With these ideas, the expert hopes that in the future cities will become increasingly inclusive and truly represent the needs of all the people who inhabit them.

Most importantly, citizens need to raise their voices when they experience inequality. “When more people are talking about these issues, they’re harder to ignore,” concludes the researcher.