Finding ways to reduce the violence experienced in cities around the world is not easy and must be approached from many perspectives, but the way we plan and build cities can help.

Today, around 56% of the global population lives in cities, and by 2050, seven out of 10 people are expected to live in them.

In 2024, Mexico topped the list of the most dangerous cities in the world. The ranking was made by analyzing homicide rates and found that Colima is number one.

However, it is important to remember that the list did not consider cities that are at war or armed conflict and that violence is not only measured by homicide rates but is much more complex.

“The current definition of violence is extensive. There is violence associated with crimes, such as robberies and homicides, sexual violence, structural violence, which has to do with lack of access and services, violence related to economic and social issues, such as drug trafficking, and others,” says Natalia García, a research professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) at Tec de Monterrey.

Throughout her career, García has focused −among other things− on studying how violence is perceived in different urban settings, such as the historic centers of cities versus the outskirts.

“I have always been interested in the subject because I grew up in a very violent context, without realizing it,” says García, who was born in Culiacán, Sinaloa, which for recent years has had a high incidence of violence associated with drug trafficking.

Understanding Violence in Cities: It Often Proliferates in the Peripheries

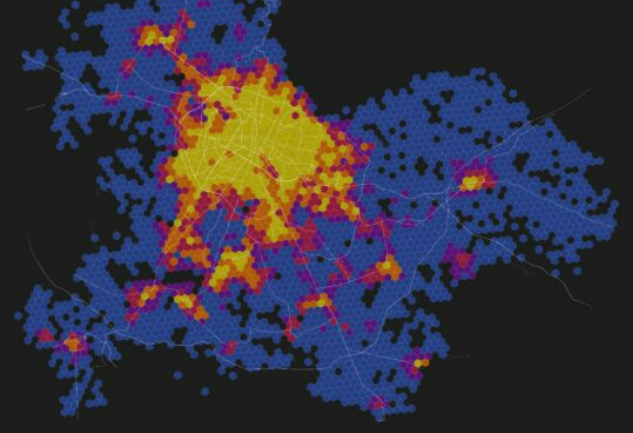

One of the first studies she did to understand how violence impacts Mexico was to compare the perception of violence in the historic centers of Aguascalientes and Culiacán with that in the outskirts of these two cities.

“In 2013, when I did the study, Aguascalientes was a safe state with low homicide rates, unlike Culiacán, which had a lot of violence,” explains García.

To her surprise, even though the statistics pointed to Culiacán being more unsafe when analyzing how the citizens of both cities felt, she found that in both of them, there was a high perception of violence.

“It was fascinating because it showed how urban planning is done differently for the city centers than the outskirts,” says the expert.

According to her, these arise disorderly, with little investment in public lighting and security.

However, the causes of violence between both peripheries were different. In Culiacán, it was associated with drug trafficking, while in Aguascalientes, it was related to criminal gangs.

When comparing the two historical centers, she found that the perception of violence was lower, but not zero, and that it was due to land use in both cases.

“They had bars and restaurants, so violence was related to disturbances in public spaces or alcohol consumption,” says García.

According to her, urban planning and crime prevention receive more funding in the centers, so violence tends to proliferate on the outskirts. The study echoes how urban planning is currently done in the country.

With her study, she demonstrated that public policies and interventions proposed by the government to reduce insecurity must consider the perceptions of the communities that live there in order to be truly effective.

Implementing generic solutions that do not consider the context tends to limit their success since they do not address the natural causes of violence.

Architectural and Urban Interventions to Reduce Crime

Beyond the work that García has done to understand how violence is experienced in different Mexican cities, over the years, other groups of architecture and urban planning researchers have found some interventions that can help reduce it.

The most classic strategy is to invest in public lighting, since dark spaces can increase the incidence of violent crimes and make people who pass through them feel unsafe.

Zoning can also help. “If you have residential areas, you can build businesses, schools, and public spaces to increase the flow of people,” says García. Also, when alcohol licenses are regulated in specific areas, it can help to reduce crimes associated with its consumption.

This goes hand in hand with investing in maintaining public spaces, since some studies have found that when there is deterioration – such as broken windows or worn facades – it can increase violence.

Crime prevention through environmental design is a multidisciplinary body of work that seeks to deter crime by designing cities with interventions such as increasing pedestrian traffic, designing the environment to reduce the places where those seeking to commit a crime can hide, as well as creating public spaces where entry is registered and security is provided, among others.

Designing parks that increase the coexistence between locals can help dignify spaces and, therefore, strengthen the sense of community.

“We all have the option to build peace daily and react to situations in non-violent ways,” says García. “If someone honks their horn at you, you don’t get out and start fighting them.”

Ensuring Security in Cities Requires the Community

Like these, there are many other interventions that can be made from architecture and urban design to reduce certain types of violence, but eradicating all its variants can only be done through a collective effort.

“Drug trafficking, for example, is a global problem that has to do with economic and political factors, so an approach from the built environment would not come close to solving it,” says García.

At the end of the day, many types of violence cannot be addressed from this perspective and require the participation of governments and public institutions to guarantee the safety of citizens.

“Violence is systemic and structural, there are systems of oppression that are normalized and made invisible, so we are no longer able to see how certain inequalities lead to violence,” says the researcher.

Are you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx