Eating healthy gets more complicated every day. Rapid urbanization around the world has led to big inequalities in access to healthy food. This motivated a group of architects and researchers from the School of Architecture, Art, and Design (EAAD, in Spanish) at Tecnológico de Monterrey to analyze the connection between urban planning and the possibility of having a balanced diet through a slightly unconventional model of selling food: Mexican wet markets known as tianguis.

According to Aleksandra Krstikj, EAAD research professor and leader of the research group, the lack of accessibility to healthy food is linked to the increasing global trend of obesity and overweight. It is difficult to maintain an adequate physical condition when we can’t access healthy products.

“We don’t have many public policies or tools focused on access to fresh food,” she says in an interview with TecScience, “and if you don’t integrate it into urban planning, you can’t have a visible improvement.”

Today, the global consensus is that diets that prevent disease and promote better health are low in processed foods, trans fats, and refined sugars, while they’re high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

But not everyone can have a healthy diet. Accessibility has to do with the fact that the places that sell fresh and nutritious food are close to the people who want to buy them. It also involves prices being reasonable for the income of each individual or family, known as affordability.

In Mexico, most people who live in cities get their food from supermarkets or convenience stores, which mostly sell highly processed foods, with excess fats and refined sugars, and little nutritional value.

“In supermarkets, only 6% to 10% of all the products they sell are fresh food,” says Krstijk. However, in the country, there is an alternative in which it is usually more likely to find fruits, vegetables, and fresh products: the tianguis.

Vindicating the Mexican tianguis

For Krstikj and the EEAD research group, tianguis are a good alternative to supermarkets and fixed stores, since it is more likely to find fresh food, but they are not usually considered in national statistics due to their high level of informality.

Tianguis are not registered with the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, are placed only a few days a week, and are not mapped or planned. “This is why currently no urban planning considers them as a source of fresh food,” says Krstikj.

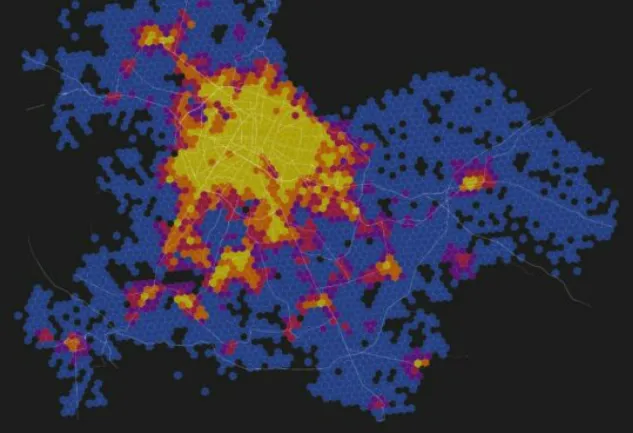

To analyze whether they are a good option for obtaining nutritious food, the group, integrated by Krstikj and Rubén Garnica from EEAD, Christina Boyes from the Center for Economic Research and Teaching, Moisés Gerardo Contreras from the National University of Mexico, and José Ramírez from Stevens Institute of Technology, mapped the availability of fresh food in different tianguis of five Mexican cities: Mexico City, Guadalajara, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro and Monterrey.

What they found was that in Guadalajara more than 60% of the stands sell fresh food, in Mexico City up to 50%, in San Luis Potosí and Querétaro around 40% and in Monterrey less than 10%.

In addition, by surveying those who sell at these stands, they found that in Querétaro and San Luis Potosí, many of the fruits and vegetables sold come from local urban gardens where the ones who sell them grow them. In Mexico City and Guanajuato, it is more common for stands to sell food from larger supply centers.

With this research, the researchers were able to prove that tianguis are a good option to get fresh products, in addition to the fact that, by selling locally produced food, they contribute to reducing the carbon footprint related to the production and distribution of food in cities.

“Sometimes people see tianguis as ugly and informal,” says Krstikj, “but to me, they are very resilient.”

Krstikj explains that unlike supermarkets and fixed stores, tianguis have great flexibility because they can be placed anywhere and at any time. They don’t depend on the rent being paid, having electricity or gas, they only need those who set up the stands to get organized and can easily change places if there’s a natural disaster or catastrophe.

Not everyone can go to the tianguis

However, even though these types of informal markets seem to offer a viable alternative for people to eat healthier food, not everyone can buy from them.

One of the branches of this group’s research was to analyze how easy it is to get to a tianguis depending on where you live. What they found was that the extremes of the population, whether they are upper-class or those who live in marginalized or peripheral neighborhoods, are the ones who have the least access to them and are the most vulnerable to poor nutrition.

In the upper classes, “the settlers themselves prohibit this type of informality on the street, in addition to the fact that they do everything by car,” says Krstikj, “it is impossible to place a tianguis there.” On the other hand, in the neighborhoods that exist on the outskirts of the cities, what abounds are convenience stores and people selling junk food.

So far, the research carried out by the group suggests that it is necessary to incorporate street markets in urban planning as an important source of fresh and healthy food.

The fact that they can be placed almost anywhere and at any time makes it easy for them to be put at strategic points so that everyone can reach them on foot or by public transport.

Some of these results are included in the chapter “Nutritious Landscapes” of the book Design for Vulnerable Communities, created by a group of architects from different institutions, led by Emanuele Giorgi from EEAD.

They also created a series of interactive maps where you can see the results of their fresh food availability analysis by city.

Currently, the group is waiting to get more funds to continue their research, since they think tianguis and healthy food access are exciting and important topics that deserve more attention.

“There is great potential in tianguis, but first you have to understand that potential,” concludes Krstikj.