“Among women and girls, there is sometimes a sense that no matter what they do, their work will not be recognized as it would be if they were men,” said Jennifer A. Doudna upon learning that she and Emmanuelle Charpentier had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2017.

The gender gap in science persists. According to UNESCO data, over half of those graduating in STEM fields, an acronym for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, are women, but only 30% are engaged in research.

These eight women scientists should know this 8M is an example of the many women who, by sharing their experiences, efforts, and ways of challenging historical debts, reconstruct the role of women in science.

Jocelyn Bell, The Power of Naming Justice

Entering physics at the University of Glasgow, Jocelyn Bell (Lurgan, United Kingdom, 1943) was the only woman among 49 men.

Years later, from Cambridge University, while analyzing records from a new radio telescope, she detected unusual, faint, regular signals just 1.33 seconds apart.

They turned out to be traces of the first known pulsars, rapidly spinning neutron stars that emit their signal like a beacon of radio waves toward Earth, flickering so precisely that they are used as clocks to test the theory of relativity.

Bell’s discovery earned her thesis professor a Nobel Prize in physics; she was excluded from the award.

Years later, she wrote an editorial in Science entitled So few pulsars, so few females in which she named the injustice she experienced.

She pointed out that her youth and gender excluded her from the prize. In discussing this situation, she is critical of the lack of recognition of teamwork and the persistent idea that discoveries are the work of one person. In the days following the announcement of the award, Bell recalls that the press unfairly focused on her private life and physical appearance rather than her work. In that editorial, she stated,

“I don’t think making women braver, more assertive or more like men is the right way forward. Women should not have to adapt completely. It is time for society to move towards women, not the other way around”. From her experience, the scientist has said that “in diversity lies the success of science.”

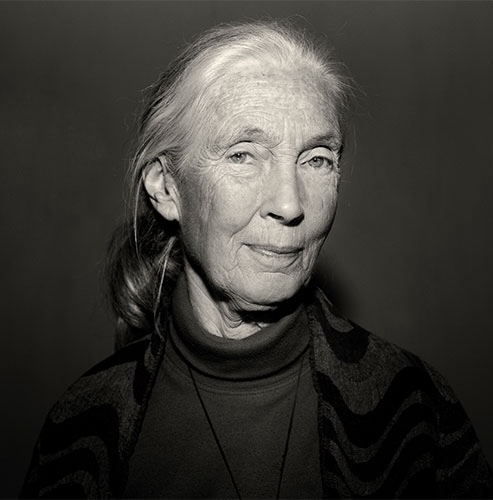

Jane Goodall, A Message About Caring

Jane Goodall’s (London, UK, 1934) passionate commitment to wildlife observation is highly motivating.

At just 23, she was the first woman to research chimpanzees in the wild in Tanzania. Her work was full of intuition and empathy, and she achieved detailed studies that revolutionized primatology. Her experiences have inspired many people to participate in wildlife conservation and ecosystem preservation worldwide.

But achieving this wasn’t easy at all because, as Goodall has shared, nobody expected a woman to do what she considered not only a job but a longing, except for her mother, Vanne, who was her companion on this adventure, since the British authorities would not allow her to live there alone.

This gesture of care, acknowledged by Goodall in telling her story, is a way of appreciating the unpaid work of care, often invisible when talking about great scientific discoveries. This is no small matter: women perform 76.2% of unpaid care work, more than three times as much as men.

Sandra Myrna Díaz, Thinking About Inclusive Futures

The climate crisis is an issue that cannot be put off. The work of the biologist Sandra Díaz (Córdoba, Argentina, 1961) has been useful in measuring part of the problem. Together with Joanne Chory, she designed a methodology to quantify the value of plant biodiversity in an ecosystem, its usefulness for humans, and its effectiveness in the fight against global warming. The importance of his research has been to delve into biodiversity as a fundamental part of human well-being.

Díaz uses her studies to highlight the relevance of science in policy formulation. In multiple interviews, she has courageously emphasized that climate change denial responds to economic and political interests.

She coordinated the Terrestrial Ecosystems Group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), intending to seek comprehensive and sustainable solutions. Thanks to her contribution in this field, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007, along with a group of specialists dedicated to developing and disseminating knowledge on climate change.

Nubia Muñoz, Researching Health from a Gender Perspective

There is one scientist who has demonstrated the value of conducting public health research with a gender perspective, and that is Nubia Muñoz (Cali, Colombia, 1940).

This outstanding Colombian epidemiologist has led numerous research projects on cancers associated with infectious agents. Among them, cervical cancer and human papillomavirus (HPV) stand out; her studies in 30 countries resulted in solid evidence of the relationship between certain types of HPV and this type of cancer. Her work made her Colombia’s candidate for the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Muñoz’s research has contributed significantly to the prevention of a disease that claims the lives of hundreds of thousands of women every year, especially in emerging countries, and was instrumental in the development of the first vaccine specifically aimed at preventing cancer.

Nisreen El-Hashemite, The Power of Paving The Way Together

Nisreen (Kuwait, 1969) was born a princess but decided to grow up as a scientist. She defied royal protocol and became a physician and geneticist. Her research led her to create a technique to diagnose genetic disorders through a single cell. Her boldness paid off: this technique is used as a preventive procedure for genetic diseases in more than 100 health centers worldwide.

Despite the value of her achievements, she noticed that she did not receive the same salary as her male colleagues, so she fought to change this situation. Years later, she stated that she did it not only for herself but for the female scientists who would come after her.

Later, she joined the UN sustainability agenda to advocate that sustainable socio-economic development will be possible by including women scientists in the plan. She became a strong advocate for gender equality in science and, as part of her proposals, launched an international platform to provide scholarships to girls around the world who aspire to study science.

She also founded the International League of Women in Science, a program designed to promote those working in the scientific field and connect them. El-Hashemite was instrumental in declaring February 11 as the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

Nisreen’s life exemplifies how women pave the way for others. This evokes what was observed in an investigation of citation biases in scientific articles due to the gender of the authors. It was found that women cite other women 40%, while men cite women 25%. This unequal recognition of work hinders women’s access to better job opportunities.

Julia Tagüeña Parga, Science Outreach Matters

The idea that increasing the presence of women in science enriches the diversity of perspectives matters when it comes to science outreach, that window to inform society about scientific work. Scientists often underestimate this work, but figures like Julia (born in the so-called Czechoslovakia, naturalized Mexican) have advocated for its recognition.

This Mexican scientist specialized in solid-state physics and renewable energies. She has held various leadership positions in Mexican institutions and conducted research in science communication. She has also participated in numerous outreach projects, including conferences and the development of museum exhibits.

In Mexico, she founded the Jorge Flores Valdés Award, which recognizes works of science communication. Tagüeña donated the prize money to visualize the importance of quality science communication for societies.

Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna

Nobel prizes, awarded since 1901, have largely ignored female talent; of 646 prizes awarded in the sciences, only 26 have gone to women. In 2017, Jennifer (Washington D.C., USA, 1964) and Emmanuelle (Île-de-France, Francia, 1968) received the medal in Chemistry.

They were recognized for developing CRISPR-Cas9, a mechanism inspired by bacteria’s natural defense against viruses. This tool has been described as a molecular scissors used to make precise incisions in the 3 billion letters of DNA that make up the code of life. Its use has been fundamental in basic science research, making it possible to obtain crops that resist mold, pests, and drought. Its application in cancer therapies and the cure of hereditary diseases is being investigated in medicine.

Following the announcement of the award, Jennifer A. Doudna commented, “Among women and girls, there is sometimes a sense that no matter what they do, their work will not be recognized as it would be if they were a man. I hope this award and its recognition will change that at least a little bit and encourage other women in science, or even in other fields, to notice that their work can be honored and have a real impact.”