Neurobiologists from the University of California have performed research on mice to discover how fear works in the brain. The study, published in Science, shows how tension and stress can become panic attacks and conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They also found a way to block this emotion.

The perception of any kind of threat, whether real or imaginary, triggers a fear response. Our nervous system is programmed to feel this emotion, as this is a survival mechanism that tells us that we should stay alert and avoid perilous situations.

The problem arises when this phenomenon is triggered in the absence of tangible dangers. People who have suffered from episodes of severe or potentially fatal stress can later experience intense feelings of fear, including during situations that lack an authentic threat.

This excessive generalization of fear is psychologically damaging and can cause conditions such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), whose symptoms can include flashbacks, nightmares, and severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the situation.

How Does Fear Work in the Brain?

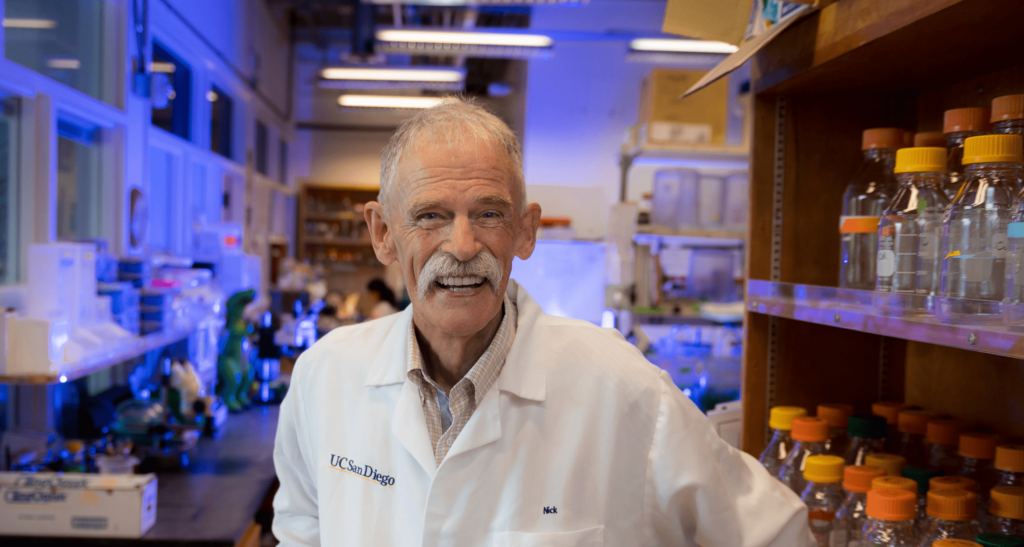

Until now, the mechanisms induced by stress that make our brain produce feelings of panic in the absence of danger have been little understood. Neurobiologists from the University of California, San Diego (USA) have identified the changes to brain biochemistry in rodents and mapped the neural circuits that provoke this negative experience.

“Our work provides a new perspective on the origin of generalized fear, which is that produced after acute stress in the later absence of a real threat, as occurs in PTSD,” said researcher Nick Spitzer, lead author of the study published in the journal Science, to the SINC agency.

Moreover, this research provides new insight into how panic responses could be prevented. “Given the current number of crises around the world, we can predict that the incidence of PTSD will rise. Our results may lead to a gene therapy for preventing the development of generalized fear,” added Spitzer.

How Do the Mechanisms of Fear Work?

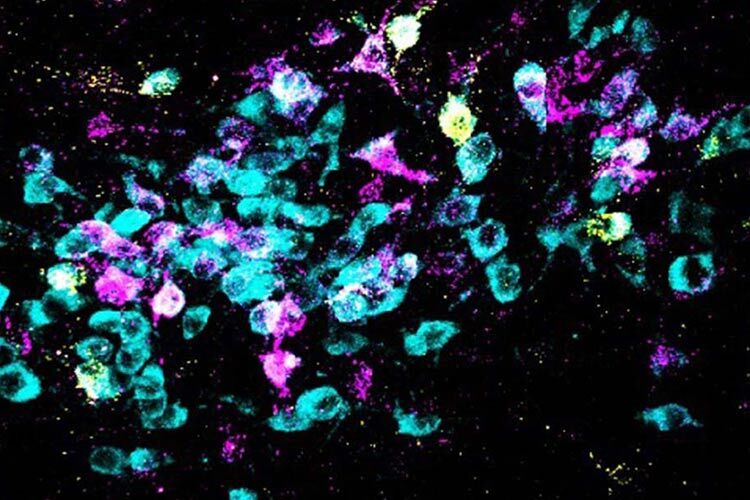

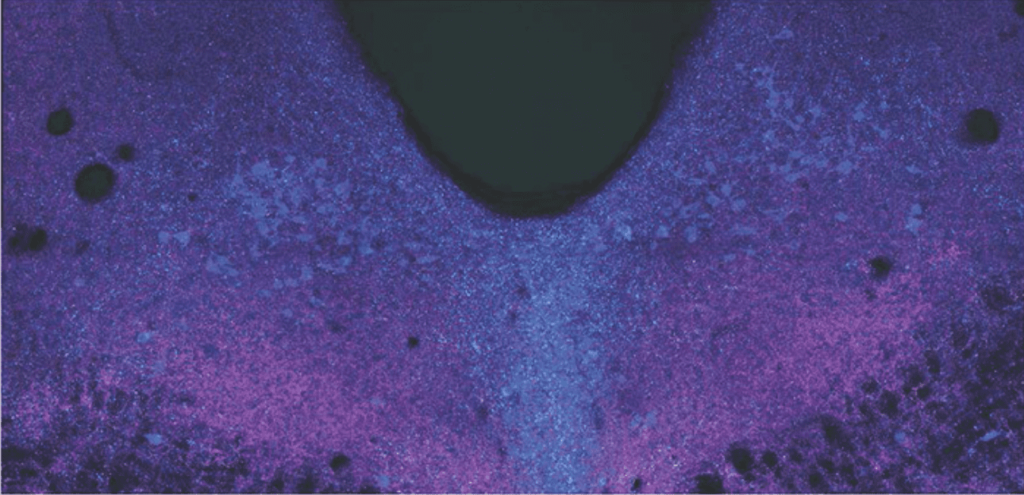

The team has described how acute stress provokes a change in the identity of neurotransmitters (chemical substances released by neurons to communicate between each other) in a region of the midbrain in mice.

“We discovered that these neurons stop producing one neurotransmitter, glutamate, which excites the neurons they’re connected to. So, these start to produce another neurotransmitter, GABA, which inhibits the neurons they’re connected to. This modification of the neurotransmitters leads to the mice showing generalized fear,” explains Spitzer.

So, when the researchers prevented the appearance of GABA, the mice did not experience this emotion. “The benefit of understanding these processes at this level of molecular detail allows an intervention that is specific to the mechanism that drives related disorders,” he went on to say.

Based on this finding, the experts examined the postmortem human brains of individuals who had suffered from PTSD. A similar glutamate-to-GABA neurotransmitter switch was confirmed in their brains as well.

How Can the Condition of Patients with PTSD Be Improved?

When mice were treated with the antidepressant fluoxetine (branded as Prozac) immediately after a stressful event, the transmitter switch and subsequent onset of generalized fear were prevented.

Not only did the scientists identify the location of the neurons that switched their transmitter, but they demonstrated the connections of these neurons to the central amygdala and lateral hypothalamus, brain regions that were previously linked to the generation of other fear responses.

“Now that we have a handle on the core of the mechanism by which stress-induced fear happens and the circuitry that implements this fear, interventions can be targeted and specific,” said Spitzer.

Although many studies have been carried out into fear conditioning, which is produced when an individual is placed again in an environment where they had been exposed to stress before, relatively few works have been done on the origins of generalized fear.

However, it is important to bear in mind that this research has examined mice as a model for humans. “It is imperative to keep working to determine, in controlled studies, whether fluoxetine is safe and effective at treating people who have experienced acute stress,” emphasized the researcher in an interview published by the SINC agency.