To measure the environmental impact of cocaine trafficking, the team designed a model that maps routes and analyzes the production chain—from cultivation to export.

Moreover, the study was presented at the 2025 Third Latin American Congress on Social Sciences and Government, organized by La Tríada at Universidad de los Andes, with a focus on violence and insecurity in Latin America.

According to Sandra Aguilar-Gómez, professor and researcher at Tec de Monterrey’s School of Government, answering that question required breaking down the whole process: from growing coca and producing cocaine to maritime, land, and air export routes.

“We didn’t just want to find a correlation between crime and environmental degradation; we wanted to show that crime causes it. And to do that properly, we need to accurately map the distribution of this entire value chain,” she says.

Satellite data and algorithms to track the footprint of crime

One of the main challenges in studying organized crime is the scarcity of reliable data. The team used satellite imagery detecting coca crops from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), along with data from the Colombian government.

“We had seizure data from every step of the production chain. Most of it came from vessels, intercepted boats, and vehicles stopped at borders or airports,” Aguilar-Gómez explains.

Economics, territory, and criminal efficiency

The next question was inevitable: How do points of origin connect to export routes? Aguilar-Gómez explains that organized crime operates like a network of companies seeking to minimize costs. “What we need to identify is the lowest-cost route connecting that origin to that destination. That’s where geography comes in,” she says.

However, Colombia’s terrain—cut by the Andes and the Amazon basin—turns trafficking into a complex logistical puzzle that must account for multiple variables. “It didn’t occur to us at first to think of criminals as behaving like any other business, but what is new in our research is the sheer amount of data and computing power we used,” she adds.

Mapping cocaine routes, pixel by pixel

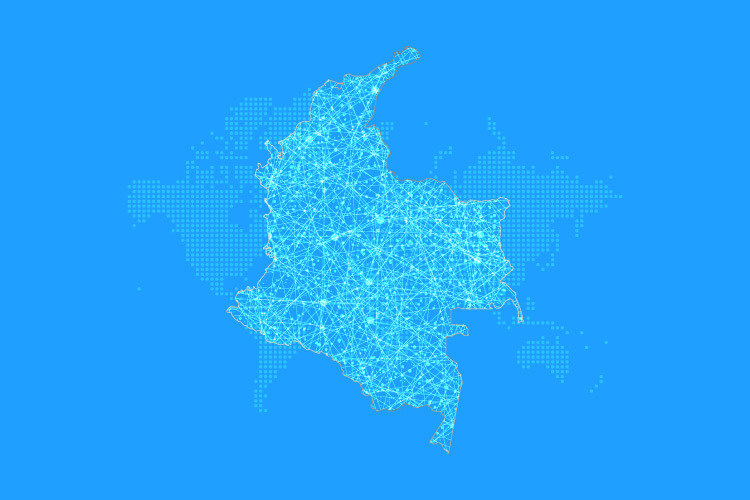

To do this, the researchers transformed Colombia’s map into pixels—each representing one square kilometer and containing information on elevation, roads, state surveillance, crops, and other variables. With the help of an algorithm, the team mapped the routes most favorable to trafficking.

Alongside Aguilar-Gómez, the study involved Diana Millán, Lucas Marín, and María Alejandra Vélez. Although the paper is still under review, the team found that 64% of Colombian territory lies within twenty kilometers of a cocaine route, and 78% of those routes are fluvial.

If you found this story interesting and would like to publish it, contact our content editor to learn more: marianaleonm@tec.mx