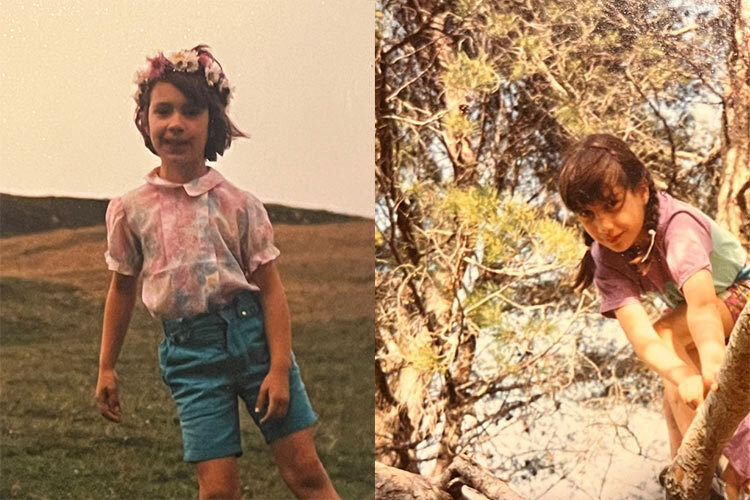

When she was a child in Avignon, in southern France, Marion Brunck imagined that a scientist was, by necessity, an older, white man with an impeccable lab coat, looking through a microscope. Perhaps, for some girls, that image might have limited their curiosity about research, but not for her. “I never had that barrier in my mind,” says the researcher while describing the fascination she felt for scientific discoveries and laboratories. When she was 12 years old, she received a microscope for Christmas and spent hours in the garden, collecting leaves, rummaging in the dirt, and preparing samples to observe. “That image of what I was at 12 years old aligns more with my current idea of a scientist: someone who gets their hands dirty working.”

Thanks to that hard work, this year, two organizations have recognized the researcher from Tec’s Institute for Obesity Research. First, by the Society for Leukocyte Biology for Excellence in Leukocyte Biology and, more recently, the International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS) distinguished her as one of the 15 emerging stars in her field.

What does this recognition mean to you?

It’s amazing because I competed with people all over the world for this prize. In the case of the International Union of Immunological Societies, there are only 15 awardees, and we are only two from Latin America. I’ve been working really hard since I arrived in Mexico. I was coming from Australia, where I studied for my PhD and post-doc, and there are clear differences in terms of infrastructure and funding. That’s why it’s important to recognize the quality of the work that is being done in the global south.

How is it to share these ideas with other researchers at conferences and environments like the IUIS, the largest immunology conference that brings together 3,000 people?

As part of the prize, we are given a session at primetime during the conference in Vienna in August. There, we will have an opportunity to share what we’re doing in Latin America. People think we don’t have the same capacities, funding, but we do have human resources and a lot of grit and we can make things happen. I’m presenting just after Yasmin Belkaid, the director of the Pasteur Institute. She’s going to see my talk. So it’s a mix of excitement and a little bit of nervousness.

A Personal Experience Turned Into a Solution for the World

Since 2018, Marion has led a team of master’s and doctoral students at Tec through two lines of research. One of them, which she will present in Vienna, is about how maternal obesity affects immune cells that are transmitted through breast milk. Her second area of interest comes from a personal experience with her mother.

My mother recovered from breast cancer, but she had a very big episode of neutropenic fever —a potentially life-threatening complication that occurs when, after chemotherapy, the body loses its defenses and can’t fight off infection. What I realized at that moment is that there’s no treatment. That was really frustrating. I was a PhD student and going back to Australia, in the institute where I was working, there were some researchers who were producing neutrophils from stem cells.

What are neutrophils and how do they affect cancer patients?

Neutrophils are key cells in the response to infections since they are the first to act and, if there aren’t enough, the person can become seriously ill, as the pathogen can reproduce without control. This is critical in patients who are in chemotherapy since this attacks cells that divide rapidly, like cancer cells, but also, unfortunately, neutrophil progenitors, which also divide rapidly due to the constant production needed in the blood. Thus, patients can become neutropenic, which leaves them defenseless.

So, it’s a therapy to treat cancer side effects, not the disease itself.

Yes, it’s for the side effects. There are medicines that stimulate the remaining progenitors to replicate faster, but it’s not always enough. A logical alternative would be to administer neutrophils from a healthy person to a patient with deficiency. This has been attempted several times, with varied results. We are conducting meta-analyses to determine if it really works or what its effectiveness depends on (patient weight, age, type of cancer or pathogen).

The Origin of a Scientific Passion

How did your family support you in developing your curiosity as a researcher?

My parents are not scientists; no one in my family is. My mom had a daycare and dealt with parents and some of them were scientists. I fondly remember a climatologist who studied clouds in southern France. My mom mentioned to him that I liked science and asked if he could show me what he did at work every day. I loved going to the laboratory, seeing those interesting machines and the excitement in the scientists’ eyes when they get a result. I could feel the energy and I thought: this is what I want to do.

Eventually you went to the University of Queensland in Australia for your doctorate. How was that transition?

At first it was a bit difficult: I didn’t speak English, I didn’t know how to enter academia as a researcher. Life has constantly thrown challenges at me and that has given me an advantage as a scientist. The younger you start solving problems without getting stressed, you get a small boost with each solution. Then you move on to bigger problems, and so you advance little by little. That’s how I won this award. I simply haven’t allowed anything to stop me.

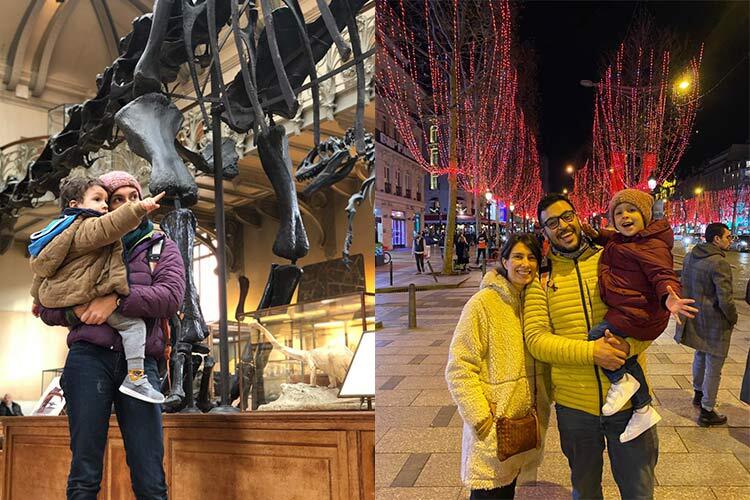

Marion Brunck met her husband Cuauhtémoc Licona – current director of the Centro de Biotecnología-FEMSA – in Australia. After finishing their postdoctorates, both sought opportunities at different universities around the world. Marco Rito Palomares, current director of the Institute for Obesity Research, contacted Licona to offer him a position at Tec de Monterrey. Licona showed interest and asked if his wife, also a scientist, could join the faculty.

“Marco always tells that story: he contacted Cuauh and told him, ‘Well, I thought your CV was good, but your wife’s CV is even better!'” Marion says with a laugh. Shortly after, both were in Monterrey and she began adapting to this new country.

Scientific Leadership

What were some things you had to adapt to when you arrived in Monterrey?

Leading meetings. I was used to someone telling me if my results were good or what I would focus on the following week. I remember that for the first lab meetings with my group I thought: “I have to prepare myself. I have to push them to get the best out of this experience.” Becoming a leader is not easy.

What were the most important skills you had to work on?

Organizing academic lab life according to my principles. Instilling passion in my students because it’s a lot of work and expectations are very high. I ask them to work hard and I will also work like that for them. I want that to be very clear from the beginning. But when they graduate they know they will have the best product.

What do you look for in your team?

Communication. We all face problems in our lives and we can overcome them, but I need to know about it. Throughout my eight years at Tec, I have realized that if there isn’t good communication, things won’t work. With good communication, we solve everything.

I always tell them: “Your competition is not next to you. Your competition is Harvard.” It’s difficult for them at first, but they fake it until it becomes reality. You do it even if you don’t feel capable. You start with small things. You have to choose your objectives and goals, and gradually increase them. I do that for my students: I simply move the target, I push them.

How important then is determination for a scientist’s work?

I think it’s an extremely important characteristic. I can’t emphasize it enough: determination and hard, solid work are needed. There’s no secret; it’s simply doing your part and focusing day by day, doing the best you can. I don’t think: “oh, I hope to win an award someday.” Awards are something you see, but before them, we don’t usually write articles about rejections or problems. A bad result only changes the direction of your path a little, but you keep moving forward.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx