The cases of fentanyl consumption that are registered in Mexico are few and are concentrated on the northern border, according to a federal government report published two years ago. However, the country seeks to ban the substance, including for medical purposes and has been accused by politicians of the Republican Party in the United States of being a producer and route of transfer.

Now, scientists and health professionals are asking to review the options before banning fentanyl, which is used as an anesthetic in surgeries and palliative treatments.

Where does fentanyl come from? What is fentanyl used for?

The painkiller was synthesized in 1960 by physician and researcher Paul Janssen while he was looking for an opioid with the positive properties of morphine, such as its ability to eliminate pain, but that produced these same effects more quickly and took less time to be discarded by the body.

As a result, he obtained a product that was 100 times more powerful and extremely fast acting.

“It has an extraordinary speed in reaching the central nervous system and is capable of producing analgesia with a very small amount,” explains Silvia Cruz Martín del Campo, a researcher specializing in the neurobiology of addiction at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies (CINVESTAV).

According to the researcher, the fact that it is 100 times more powerful does not mean that it is stronger, but rather that 100 times less substance is needed to produce the same results. In addition, it has anesthetic and sedative effects.

The problem with fentanyl addiction

Due to these characteristics, fentanyl was quickly adopted by the medical community to induce anesthesia in brief surgeries and eliminate pain in patients with terminal cancer or other conditions that cause intense physical suffering.

For decades, its use in the country has been well-regulated and has helped to mitigate the consequences of the historical shortage of morphine and opioids for the treatment of pain.

“We have coexisted with fentanyl for 50 years without problems; doctors, anesthesiologists, and palliative care providers consider it a fundamental tool,” says Cruz Martín del Campo.

However, in recent years, fentanyl synthesized in clandestine laboratories began to be mixed with illegal drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

Today, it is sold in pill forms that can be taken recreationally and has led to an increase in overdose deaths in various countries around the world.

Banning its use does not solve the crisis

Faced with mounting evidence of this crisis, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador recently proposed banning the use of fentanyl in Mexico and replacing it with another drug. In response, the scientific and medical communities have questioned that possibility.

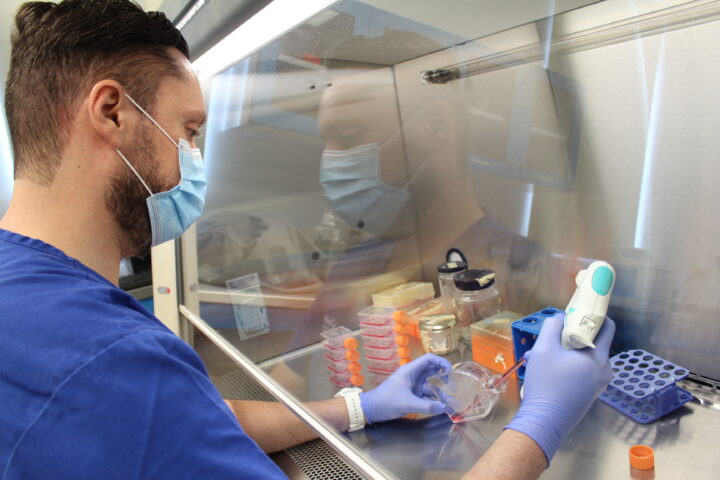

“I think it would be a mistake for the government to prohibit the creation, production, and distribution of fentanyl for the health sector,” says Oswaldo Cuauhtémoc Zamudio, chief of operating rooms and anesthesiology at TecSalud hospitals.

“You take away the opportunity of not feeling pain from patients,” he says.

According to the anesthesiologist, using this pain reliever in his practice is frequent, useful, and safe, in addition to being heavily regulated. To get it, he must pass various filters and strict reviews by government authorities such as the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risks (Cofepris).

Oswaldo Cuauhtémoc Zamudio, chief of operating rooms and anesthesiology at TecSalud hospitals. (Photo: Courtesy)

Medical use of fentanyl

According to Cruz Martín del Campo, it is essential to understand that the fentanyl used in hospitals is not the same as that sold on the streets.

“Pharmaceutical formulations are made in such a way that they are safe in adequate concentrations, the one sold on the streets is poorly synthesized, has no quality control, and is made in massive quantities,” she explains.

The researcher says that banning fentanyl is like “having a flood due to rain and you want to solve the problem by closing the water faucet. Now you’re going to have two problems.”

For her, prohibition will only worsen the crisis related to the shortage of opioids for pain management and will not help solve the abuse crisis on the streets.

Three alternatives

The problem has multiple aspects that can only be solved with the collaboration of all sectors of society. While the authorities must be in charge of controlling drug trafficking and the illegal production of fentanyl, the scientific community proposes measures to reduce deaths from overdoses and treat people addicted to it.

According to Cruz Martín del Campo, there are three strategies that would help with this.

The first one is to have naloxone available to everyone. This is an opioid antagonist that binds to opioid receptors in the body and brain and rapidly reverses an overdose. It is available in injected or nasal spray form.

In countries with opioid crises, such as Canada and the United States, the substance is available at gas stations, pharmacies, and supermarkets, so anyone can access it and save someone in need. However, in Mexico, the sale of this substance is heavily regulated and not easily available.

The second route is to create “Good Samaritan laws”, making sure that people who rescue someone from an overdose don’t face criminal charges.

“This is about that if you’re trying to save someone’s life, whether you’re using or not, you don’t go to jail, but that doesn’t exist in Mexico,” highlights the CINVESTAV researcher.

Lastly, the scientist suggests having specialized clinics for addiction to opium-derived substances.

In rehabilitation institutions, medication-assisted treatments should be offered, enabling people with a dependency to be administered much milder opioids, such as methadone. When entering the body and activating the same receptors as fentanyl or heroin, other substances help with the drug withdrawal symptoms.

The researchers interviewed agree that these proposals aim to build a society where the use of psychoactive substances implies regulation and information that allows citizens to make free and safe decisions regarding the consumption of these drugs.

“In the meantime, we cannot punish patients or those who are dependent on opioids with pain,” stresses Cruz Martín del Campo.