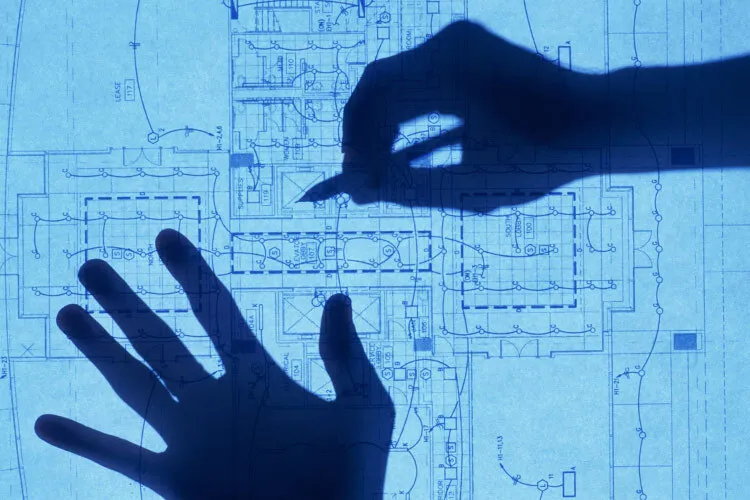

People who are on the autism spectrum are not usually considered in the design and construction of spaces such as schools, parks, or auditoriums. That is why designers and architects worldwide seek to promote an inclusive vision, particularly for places intended for learning.

“We lack a lot of empathy and inclusion in architecture and design,” says Mariana Maya López, research professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) at Tec de Monterrey, in an interview with TecScience.

Although we often do not stop to analyze them and take them for granted, the physical spaces in which we develop have an important effect on our lives, including cognitive aspects such as attention, learning, and orientation.

The places where we develop can have beneficial or detrimental effects on our abilities, encouraging or blocking us from learning something new, for example.

Generally, the perspective under which we have built our towns is adult-centric and ignores children, older adults, people with disabilities, and neurodivergent people, including those on the autism spectrum.

However, by extracting evidence from disciplines such as neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy, places that include them can be created from architecture.

The spatial needs of the autism spectrum

Autism spectrum disorder is a condition that, due to differences in brain development and connections, affects the way a person communicates and socializes with others. It is called a spectrum because it includes a range of symptoms that can intermingle and range from mild to severe.

“It is very complex, no boy or girl within it fits into a standard,” explains Maya. In Mexico, almost 1% of children live within the spectrum.

Among its many symptoms, they have difficulties in verbal and non-verbal communication, understanding concepts, or imaginative and creative limitations. All this represents an impediment to their traditional learning.

For people with autism, and neurodivergent people in general, to perform better in school, the design of the environments where they learn must be accessible and sensitive to the specific challenges that these conditions represent.

With the firm belief that architecture has the power to facilitate the learning and development of neurodivergent people, Canadian architect Magda Mostafa, now based in Cairo, has pioneered architectural design focused on them.

The researcher proposes that design principles be used in the construction of classrooms and schools, including acoustics, where background noise, echo, and reverberation are sought to be minimal. Neurodivergent people are often sensitive and distracted by these sounds.

She also proposes creating escape spaces: delimited, outdoor areas, surrounded by trees and vegetation with natural sounds that provide an escape from spaces with many stimuli, such as classrooms.

Throughout her career, she has demonstrated that the attention and learning levels of children with autism benefit when these principles are considered.

The first investigations in Mexico

Echoing this research, López has participated in projects in Mexico to improve design and architecture practices to include people on the autism spectrum.

In general, the designer has focused her efforts on social innovation, which focuses on addressing the specific needs of vulnerable individuals or societies.

“It’s about putting yourself in people’s shoes and using the perspectives that research gives you to create products or spaces that respond to their needs,” says Maya.

In 2021, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, she participated in a research project that sought to analyze the importance of the built environment to promote learning in infants with autism.

To investigate this, they surveyed mothers of children on the autism spectrum between 4 and 14 years of age about what they observed in terms of their children’s reactions to learning spaces.

“It was an incredible listening process,” she says.

Among their discoveries, they found that most children within the spectrum love water, green places, and natural sounds, as they help them regulate their emotions. They also found that they usually need spaces to run or disperse, as well as others to take shelter.

With this and other work, the designer hopes that schools and universities will be designed to include all people, including those who are neurodivergent.

However, she warns that more studies are needed to be carried out with the help of people who live in the spectrum, to consider their perspectives and to be able to inform decision makers, architects, and construction companies about the principles that should be considered to include them.

“Together we can establish a dialogue and find what we can do to improve the conditions of people with autism,” concludes Maya.