In a study conducted in Mexico, researchers examined the long-term consequences of having either a troubled or a nurturing childhood. The study, which surveyed 1,448 adults and 200 minors, was conducted by a team of approximately 80 people, including researchers and field interviewers. Among the most striking findings: 88% of participants reported experiencing at least one adverse childhood experience.

The results, published in The Lancet, underscore the urgent need to implement public policies that mitigate the negative impacts of childhood adversity and promote positive early-life experiences.

“Having this study published in The Lancet is a mark of recognition and international prestige. It’s one of the most respected medical journals in the world, and being featured there is a seal of quality,” said Julieta Rodríguez de Ita, a pediatrician at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences and leader of the Developmental Biology and Childhood Well-being Research Group.

Fieldwork and Measuring Positive Experiences

Roughly 50 people were trained to conduct the interviews, as they included sensitive topics such as physical and emotional abuse.

“Our publication reflects that adverse childhood experiences are a far-reaching public health issue. We’re proud to bring the voices of Mexican children to the global stage,” said Rodríguez de Ita.

The study revealed that 22% of adults had experienced more than four adversities during childhood. These individuals showed a significantly higher risk of developing obesity, hypertension, migraines, irritable bowel syndrome, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder. However, the study also looked at positive experiences: 50% of participants reported having meaningful, nurturing moments in their childhoods.

Daniela León Rojas, a psychiatrist and professor at TecSalud, led the clinical and fieldwork components of the research.

“Fieldwork was critical. Since we were collecting highly sensitive data, the interviewers needed to know exactly how to ask the questions—and just as importantly, how to remain composed and to act accordingly while doing so,” León Rojas explained.

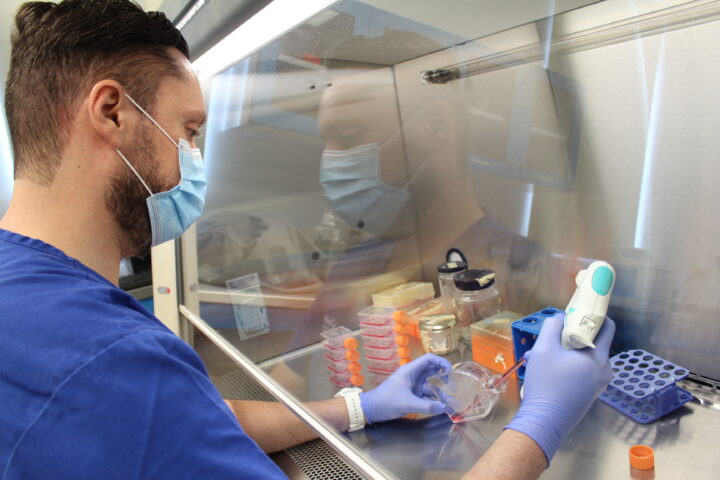

Biological Sample Collection

Funded by the Tec de Monterrey Center for Early Childhood and the FEMSA Foundation, the study went beyond surveys and questionnaires. The team also collected biological samples—blood, urine, hair, and feces—to explore how early experiences are reflected in the body.

“We aimed to understand the biological impact. Caregivers or parents provided consent. For example, we collected hair samples to measure cortisol, a well-known biomarker of stress,” said Fabiola Castorena, an expert in translational medicine and professor at TecSalud.

Specially trained fieldworkers collected the samples using equipment designed to maintain the proper temperature. According to Castorena, Tec de Monterrey medical students also took part in analyzing the samples.

These biological samples are part of the study’s second phase, which follows the initial stage of population-level diagnosis.

“Measuring biomarkers takes time and a great deal of effort. We already have some preliminary results, but we expect to translate these into scientific publications later this semester and into the next,” Castorena added.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx