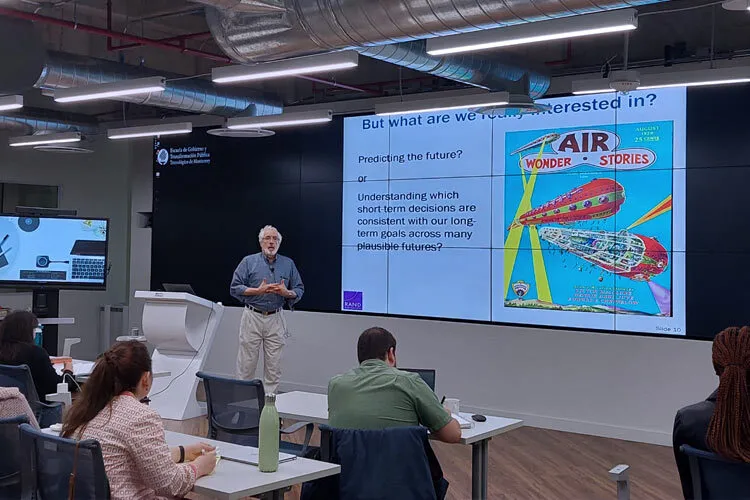

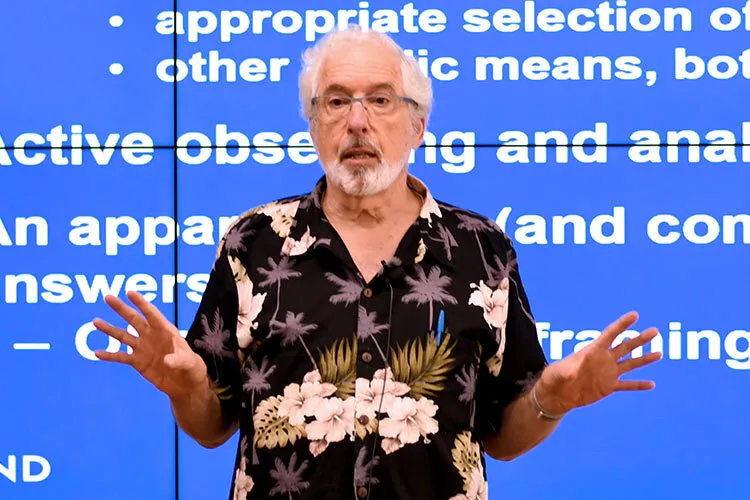

Steven Popper is a senior economist at the RAND Corporation, a non-profit research organization that focuses on developing solutions to improve public policy decision-making and public understanding of public policy issues.

He is also a professor of Science and Technology Policy at the Pardee RAND Graduate School, which was the first fully accredited graduate school to offer a Ph.D. in policy analysis in 1970.

From 1996 to 2001, he worked as associate director of the Science and Technology Policy Institute and provided analytic support to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Currently, he and his colleagues focus on developing tools to aid decision-making under conditions of deep uncertainty.

This year, Popper will be joining the Faculty of Excellence at Tec de Monterrey, an initiative dedicated to bringing extraordinary, world-renowned professors with distinguished experience.

Also, for the second year, he and the Society of Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty (DMDU) offered a two-week summer school at the School of Government and Public Transformation.

Popper explains that Tec de Monterrey wants to be part of a transformation in the public sphere in Mexico. (Photo: Courtesy of School of Government and Public Transformation)

Decision-making process under uncertainty

Why is it important to study decision-making?

I think the need for us to study it is not just an academic exercise, we seek to apply to real-world situations.

If you look at democratic countries around the world, there is a fundamental problem: they are being asked to address challenges that the creators of those institutions never dreamed of, this is a problem because democratic institutions of governance are perceived as being ineffectual or slow.

One of the reasons to study this is to enhance the capacity for democratic institutions, from the national level down to the state down to the local community level, to be able to more effectively deal with the complexity of today’s problems.

There are a lot of factors, a lot of uncertainties, and a lot of unknowns, and your head is exploding with it all, so what are the things that you should really pay attention to in deciding between course of action A and course of action B?

How did you become interested in decision-making?

I deal a lot with science and technology policy, and I just found that the tools that I had available to me were unsatisfactory. So, my interest in decision-making, and particularly supporting policy, really comes from the nature of the organization I work in and the missions that it is trying to fulfill.

Since 1948, we had this incredible toolkit of analytical techniques that were now taught in schools of operations, research and business schools and so on, what I and a group of colleagues became aware of −starting in the late 80s, early 90s− was that there was a class of problems emerging for which these tools were not as useful, or even dangerous to apply.

It would give you an illusion of control that really was not there. And these problems were characterized by what I and others came to call deep uncertainty.

What is deep uncertainty?

Deep uncertainty occurs when you don’t have the information to know or agree on what probabilities to put on the possible future. We can’t really use probabilities to characterize this uncertainty.

This happens because policy-making not only involves planners and decision-makers there are also stakeholders and important constituencies, there are interests involved.

Another condition that can cause it is when we don’t know or we cannot agree on how the world works; whether if we do a particular policy action, it has the effect that we wanted to have, or it has less of an effect, or perhaps a completely negative effect.

For a lot of things, we kind of understand how the system works, but there are things where we really don’t agree. And that’s why you have people who are looking at the same data and that will come up with very different conclusions.

And then there’s a third that I call deep controversy, which is how we should evaluate policy outcomes. We do a policy, and a lot of things could change or go wrong.

So, under deep uncertainty, a lot of the tools for decision support really kind of break down, they really don’t apply. If what we’re really trying to do is predict the future, then we’re in real trouble because we can’t. It’s not because we’re lazy, it’s not because we haven’t done the work, it’s because we just don’t have the ability to do it.

Predict the future

How can we better predict what’s coming?

If you’re trying to be predictive, if you’re trying to decide which set of currently unknowable assumptions is the correct set for the future, then you have a lot of work ahead of you.

What we’re really doing when we get those predictions is answering a different question; which is, given the uncertainties that are present, how should I think about short-term decisions in light of my long-term goals? What are potential solutions or strategies or courses of action or policies that we can follow that we have reason to believe will help us achieve our long-term goals across a wide range of possible futures?

And so that’s really kind of the essence of the idea of decision-making under deep uncertainty.

Could the work you do help us face a health crisis like COVID-19 pandemic in a better way?

Yes, a pandemic is precisely where this kind of decision-making under deep uncertainty really helps. All of a sudden you have a huge crisis, and you have very little information, you have a lot of opinions, and even medical science changes.

We didn’t know the rate of mutation, we didn’t know whether COVID was airborne, or you could pick it up from surfaces, there were so many things that we didn’t know and you have to make some decisions, you need to decide where to allocate resources, coming up with a vaccine, funding research so we get better data on exactly what’s going on, implementing various preventive measures that are not vaccine based, and nobody really knows.

The tools that we’re talking about are precisely designed to help us navigate under those circumstances of uncertainty.

Facing tough problems

What are some of these tools you talk about?

One is a very technical tool called robust decision-making, and it’s based on computers and mathematical models of various sorts.

And the insight is that in a lot of cases, people use models to be predictive, but under deep uncertainty, it’s very difficult for these models to be predictive and people become very unhappy. The problem is that the model was asked to do something that it really can’t do. But what it does do is represent very well what we do know about how things work, and if you think about it also has entry points for things that we don’t know.

So robust decision-making is based on using models differently, which is to say not as predictive engines but as ways of generating alternative futures, and alternative cases. If we did the following policy in this sort of future world, what would that look like? We can discover a small number of scenarios that make a critical difference in success or failure.

Another one is participatory foresight. In contrast to robust decision-making, there’s no model, there are no numbers necessarily. It’s a way of trying to have structured discussions among groups of people who are otherwise unable to come up with an idea of how they should proceed.

It’s narrative based and also based on taking advantage of some of the dynamics that exist in those small groups and large groups. To put it relatively simply, you get a very diverse group of people, you divide them up into small groups, usually with opposing views, and instead of asking them what we can do to get to a better future, you kind of turn the tables on them.

Instead of making them think of the future, you give them a story set in the future and have them look backward. What’s in this story? What are the main points? Why is that sustainable? Why does that situation persist? Why is it stable? What tradeoffs needed to be made?

So you get them to paint a very detailed picture of that future and now you go back to the current situation. How do they differ? What needed to happen for that future to appear and what needed not to happen?

And then you’ll have these small groups, and the small groups will report to each other, and then you’ll be in a plenary session and work with that raw material and then you will ask how we are going to get from where we are to where we want to be.

When should these tools be applied?

In some communities the first approach would be preferred for a variety of reasons, just because of how people convince each other in that community and what’s the rhetoric of argumentation that they use. Whereas in other settings people want to talk about the problem.

Has the knowledge you acquired helped you on a personal level to come to decisions more quickly or more calmly?

I think there are a couple of things that I’ve learned from this, the first one: always start at the end. When you’ve got a really tough problem, really kind of think about, well: ok, what do I really need to know, and how should I decide this? And then that tells me how I should think about it and what sort of information I need to gather and what my process should be trying to get myself to the point where I can make that decision.

The second one: when I decide between two scenarios I ask myself; would I be able to explain to my future self the reasons why I made that decision?

Faculty of Excellence

What’s your perspective of Tec the Monterrey and what’s going to be your goal in joining the Faculty of Excellence?

I’m joining Tec the Monterrey because it’s an institution that I’ve admired, it’s an institution that has been supportive of the sort of things that I want to do, even though I wasn’t a member of it.

They have a great interest in developing their own capacity for these newer methods of decision analysis and it’s an institution that has an interest. Also, Tec de Monterrey wants to be part of a transformation in the public sphere in Mexico, and all of that is very close to my heart.

As far as the Faculty of Excellence goes, I’m honored. I was honored to be considered, I’m even more honored to be accepted into that group.

I also view it as a responsibility placed upon me to help develop the next generation and to be collaborative with other members of the Tec de Monterrey family.

I’ve been coming to Mexico since about 2002 doing projects and I’ve come to appreciate the richness, complexity, the layer upon layer of culture and history that’s represented by Mexico, I’m fascinated by it, and if I can play some small part in contributing to what Mexico can become, that would be very satisfactory in a personal level.

What’s the summer school you’re teaching about?

So the summer school, this is the second year that we have run it.

We have something like 16 or 18 people from all over the world who were invited to attend after applying. Some of them are grad students, some of them are consultants and some of them work in government or public agencies. And the idea is to give them exposure to some of the basic ideas, but also some of the tools that they can actually use to conduct these sorts of studies to apply them in the setting that they come from.