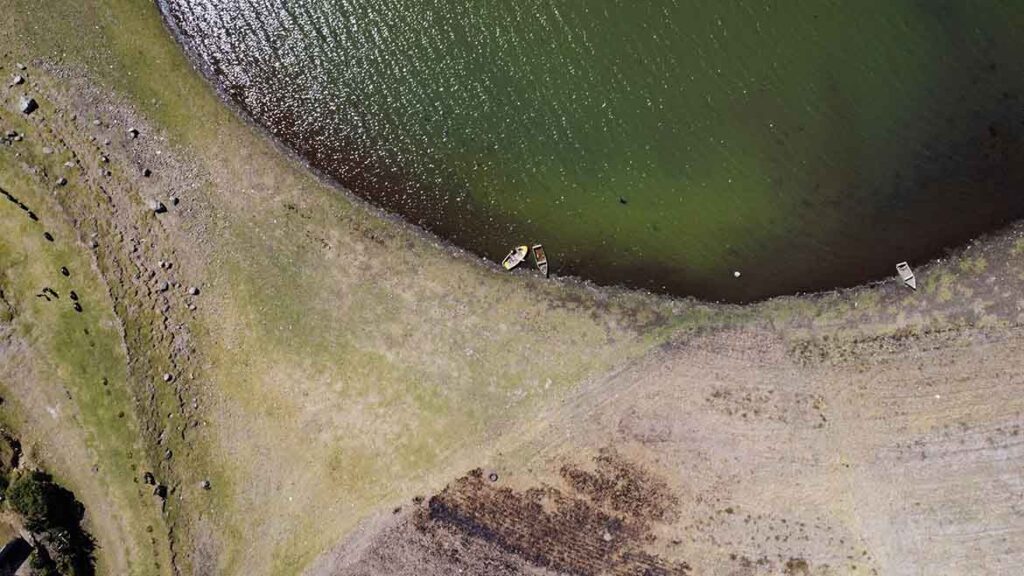

At the beginning of March, the Cutzamala Reservoir System, which provides water to Mexico City and the State of Mexico, reported storage levels of 37.59%. According to the National Water Commission (CONAGUA), the system will reach minimum operating levels this coming June 26. After that date, the system will be unable to pump any more water.

So, where did we go wrong? Specialists concur that the problem began decades ago because people didn’t understand that freshwater is a scarce and finite resource.

Why is there a Water Crisis?

“People weren’t thinking about using it more efficiently or taking steps to instill water culture. There’s also the matter of population growth. As Mexico is becoming more urbanized, demand has risen so much that local resources are no longer sufficient,” explains Aldo Ramírez, Director of the Tec’s Water Center.

Ramírez says that urban development never considers the water available in an area as a criterion for construction. Instead, land value is always established as the chief reason. This leads to us having to build water systems spanning more than 100 kilometers, such as El Chuchillo that supplies Monterrey, or the Cutzamala System itself with 322 kilometers of routes for distributing water.

On a personal note, Ramírez says that one of the greatest aberrations is that we continue to use high-quality drinking water to flush toilets.

“This is water that had a cost of extraction from water wells, an energy cost, the cost of purification, and then you use it for that. We definitely have to review this situation,” he explains.

Water Permits

According to María Eugenia García, National Coordinator of Agua para Tod@s, Agua para la Vida (Water for Everyone: Water for Life), the problem lies in thinking about water as a commodity and not as a natural resource whose priority use should be domestic.

“In terms of the number of water permits, there were 2,000 permits in 1992, and there are 564,000 permits today. This leads to water being concentrated in just a few hands,” says the activist, citing figures from a survey made in 2020 by the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM).

Her organization, which advocates for changes to the law, says that current legislation continues to allow the granting of permits that are not supervised by CONAGUA.

The activist says that solving the water problem with infrastructure costing millions of pesos to extract water from distant places is short-term thinking. Her legal reform initiative, Agua para Tod@s. Agua para la Vida, contemplates measures such as restoring groundwater flows and basins, correcting overexploitation and hoarding, recognizing indigenous peoples’ water rights, and achieving the creation of sustainable municipal and metropolitan water systems.

A Complex Resource

Current technology has enabled us to reach Mars, create Artificial Intelligence, and reconstruct the molecules of extinct animals, but it can’t help us much with the water crisis. This is the opinion of Tec researcher Sebastián Gradilla. As an engineer, he used to think that technology could solve any problem. However, he now believes that the water problem is systemic.

“Water is a systemic problem. Even when we have the technology to treat it, to distribute it, water is involved in different aspects that have to do with the productive sector, health, public policy, and governance issues. There are many interests at stake,” he explains.

He says the problem is not that there is less water, but that there is no high-quality water. This issue revolves around industry, farming, standards, and resource monitoring, as well as individual use.

“Although technology and science can show us how to generate better strategies, we have to be in permanent dialog with those who shape public policy and people in the industry,” he says.