A biomaterial developed from shrimp waste made the leap from the laboratory to the market after attracting investor interest in 2025. The non-toxic, low-cost technology enables the creation of invisible UV inks with potential applications in sectors such as pharmaceuticals, medicine, and aerospace, and serves as an example of how scientific research can be transformed into sustainable innovation.

It all began when, just one month after graduating as an engineer from Tecnológico de Monterrey, Victoria de León found herself facing a panel of investors. This took place in July 2025, when she presented her project at the first edition of Hecho en México: Mentes en Acción, an event organized by Mexico’s Ministry of Economy (Secretaría de Economía, SE) to connect scientific and technological innovations with investors capable of driving their development and bringing them to market.

The proposal centers on a material developed entirely from shrimp waste, which can be used to create invisible UV inks. The material is non-toxic, inexpensive, and has potential applications in medical, pharmaceutical, and aerospace sectors. “This isn’t competition—it’s a new industry,” de León says.

The event marked a turning point for the project. Two investors expressed interest, opening a new phase focused on technological development and eventual commercialization.

De León acknowledges that this progress would not have been possible without the support of the Eugenio Garza Lagüera Institute of Entrepreneurship at Tecnológico de Monterrey, which helped transform a scientific development into a market-viable proposal. “They trusted me to represent Tecnológico de Monterrey at the Ministry of Economy, and it changed my life,” she says.

With that institutional backing, the engineer was able to bridge her scientific training with entrepreneurship, giving rise to Ontla, a company whose name means trace of light in Náhuatl. For her, having a space dedicated to entrepreneurship is essential: “It serves as a reference point, so people feel encouraged and know where to turn.”

From Space to Earth

The path that led de León to this discovery began with her interest in the aerospace sector. While studying Robotics and Digital Systems Engineering at Tecnológico de Monterrey, she participated in the International Aerospace Program, during which she spent a week at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), tackling team-based challenges.

In a competition focused on the problem of space radiation, she began exploring materials science. There, she learned that radiation is one of the main obstacles to space missions, as it limits their duration and poses serious health risks to astronauts. Her approach was to develop detection methods using visual indicators, combining lunar soil with other materials.

That line of inquiry led her into multidisciplinary work. While taking robotics courses, she spent long hours in the lab working with biomaterials derived from nature. It was then that she experienced what she describes as a “classic eureka moment.”

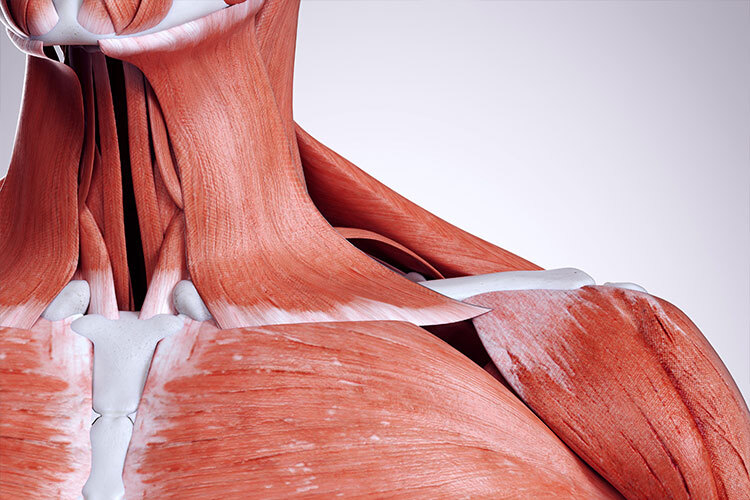

During tests with different biomaterials and light-emitting lamps, she observed that a material derived from insects glowed intensely under UV light. After reviewing the scientific literature, she confirmed that nothing similar existed: she had identified a new biomaterial.

Using it, she developed a type of wall covering for lunar habitats capable of functioning as a visual indicator of radiation caused by meteorite impacts or structural leaks. She currently holds two patents granted by the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property (IMPI).

Applications Beyond Space

Although the material’s potential for space applications was promising, de León recognized that those uses were geared toward the long term. “Space is incredible, but this is a new property, and it’s also important to see how these innovations can be brought back to Earth,” she explains.

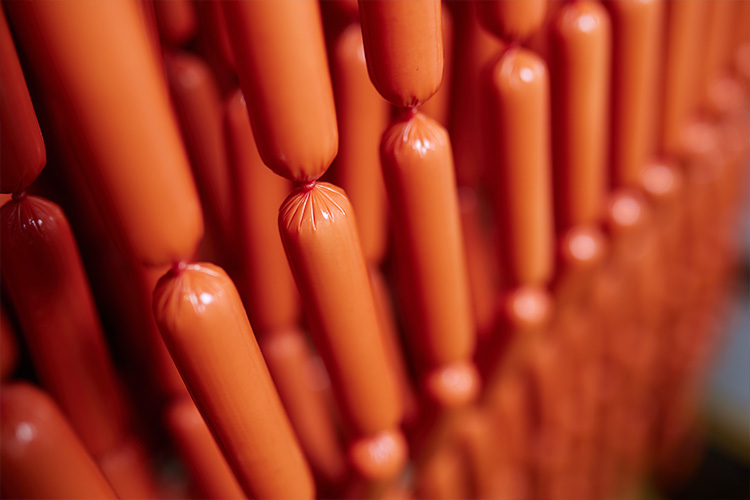

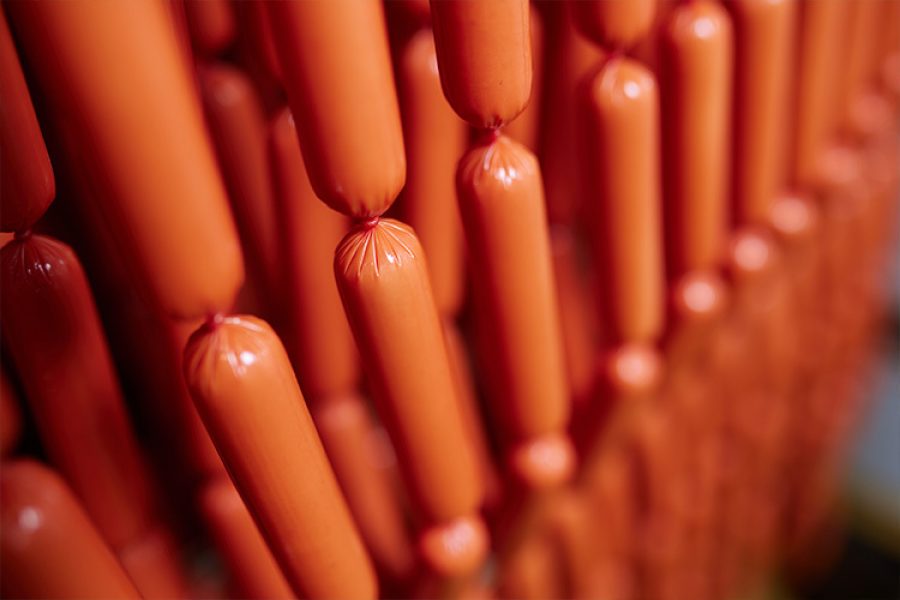

That is when she discovered that the material could also be obtained from shrimp shells. The opportunity was clear: shells account for nearly 50% of a shrimp’s total weight and typically end up as waste in the food industry.

She initially adapted her research for radiation sensors in terrestrial environments, but she soon identified a much broader market. Today, most UV solutions are derived from petrochemicals, many of which have negative environmental impacts and some of which are even carcinogenic.

Ontla’s proposal, she emphasizes, is not merely to offer an alternative. “It’s about rethinking what we mean by sustainable technology.” Because it is a biologically derived material, it is edible and biocompatible, opening possibilities in the medical and food industries. However, the application with the greatest potential impact lies in the pharmaceutical sector.

Globally, counterfeit medicines are a growing problem. In Mexico alone, in 2025, the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risks (Cofepris) issued nearly 60 health alerts related to potentially counterfeit drugs.

Ontla’s material could be used as an authenticity seal on pharmaceutical packaging. “Imagine being able to verify the authenticity of a vaccine in a hospital or a medication in a pharmacy with a simple UV seal,” de León suggests.

Bridging Science and Entrepreneurship

Currently, Victoria de León works as a researcher in biomimetic systems and materials at the Max Planck Institute in Germany. As she develops industrial applications for her material and advances an international patent, she expects to begin commercialization next year.

Her trajectory has led her to reflect on a structural challenge within the innovation ecosystem: how to close the gap between academic research and entrepreneurship. “There is such a stark separation that many academics continue advancing in their field without ever considering entrepreneurship,” she says.

In her case, the Institute of Entrepreneurship at Tecnológico de Monterrey was key to taking that first step. It also helped her strengthen her communication skills, a common need among scientists.

“If we don’t learn how to communicate the potential of our ideas clearly, we limit their impact,” she notes.

Today, de León describes her approach as philosophical engineering: before creating, she says, it is necessary to reflect on the impact of what is being developed and its significance for future generations.

Since her first pitch at the Ministry of Economy, her career has received international recognition. She has been included on Forbes’ 30 Under 30 list, selected as an MIT Innovator Under 35, and named among 3M’s 25 Women in Science LATAM.

She hopes her story will inspire new generations of students to combine science and entrepreneurship. “If we train profiles that integrate both areas, we will help drive a more innovative Mexican industry,” she concludes.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx