By Iván J. Bazany-Rodriguez, Jessica M. Muro-Hidalgo, Axel Macias-García, J. Guadalupe Hernández-Hernández, Carlos Alberto Huerta-Aguilar y Pandiyan Thangarasu

How can we tell whether the water we drink contains invisible contaminants—or whether a medical sample carries biomolecules linked to disease?

In chemical sciences, several techniques can detect these substances, including one known as photoluminescence spectrophotometry.

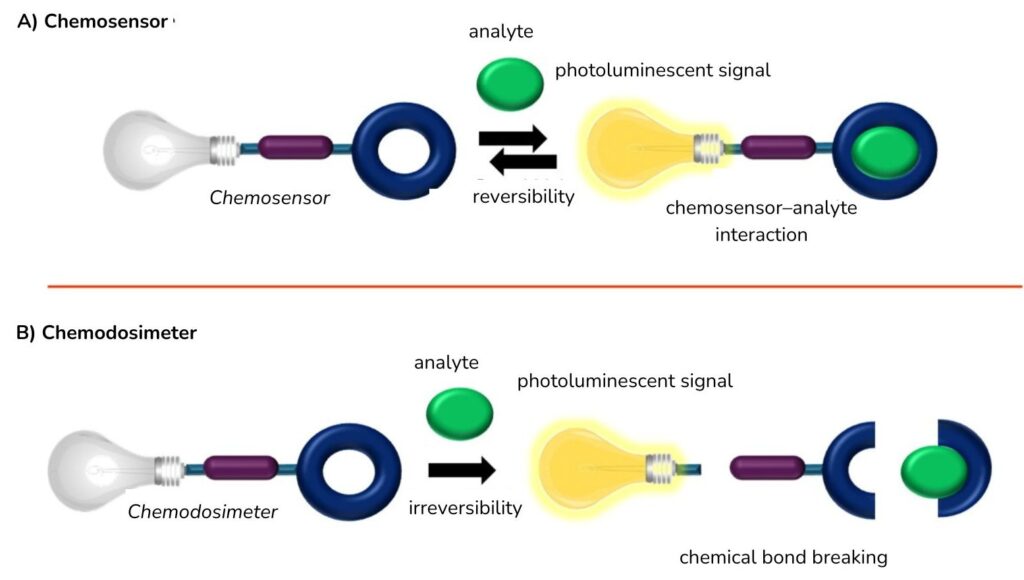

These instruments rely on molecular sensors—called chemosensors and chemodosimeters—which are synthetic compounds that react when they encounter another chemical, such as a contaminant or a biomolecule. When that reaction occurs, the sensor undergoes a change in its physicochemical properties.

If that change involves an optical property, such as light emission, the molecular sensor is considered photoluminescent.

Scientific literature has documented a variety of photoluminescent sensors containing metal ions—such as zinc, copper, aluminum, palladium, platinum, iridium, and ruthenium—that react with specific target compounds.

In our research on detecting amino acids, ions, and pesticides, we work with photoluminescent sensors derived from ruthenium ions (Ru²⁺, Ru³⁺). These sensors can detect trace amounts of compounds that are essential to the food industry, environmental monitoring, and disease diagnostics.

Ruthenium Sensors: How They Work

Photoluminescent sensors based on Ru²⁺ and Ru³⁺ exhibit strong absorption and visible-light emission bands. They’re also highly stable in water and under light exposure, making them strong candidates for detecting substances in aqueous environments.

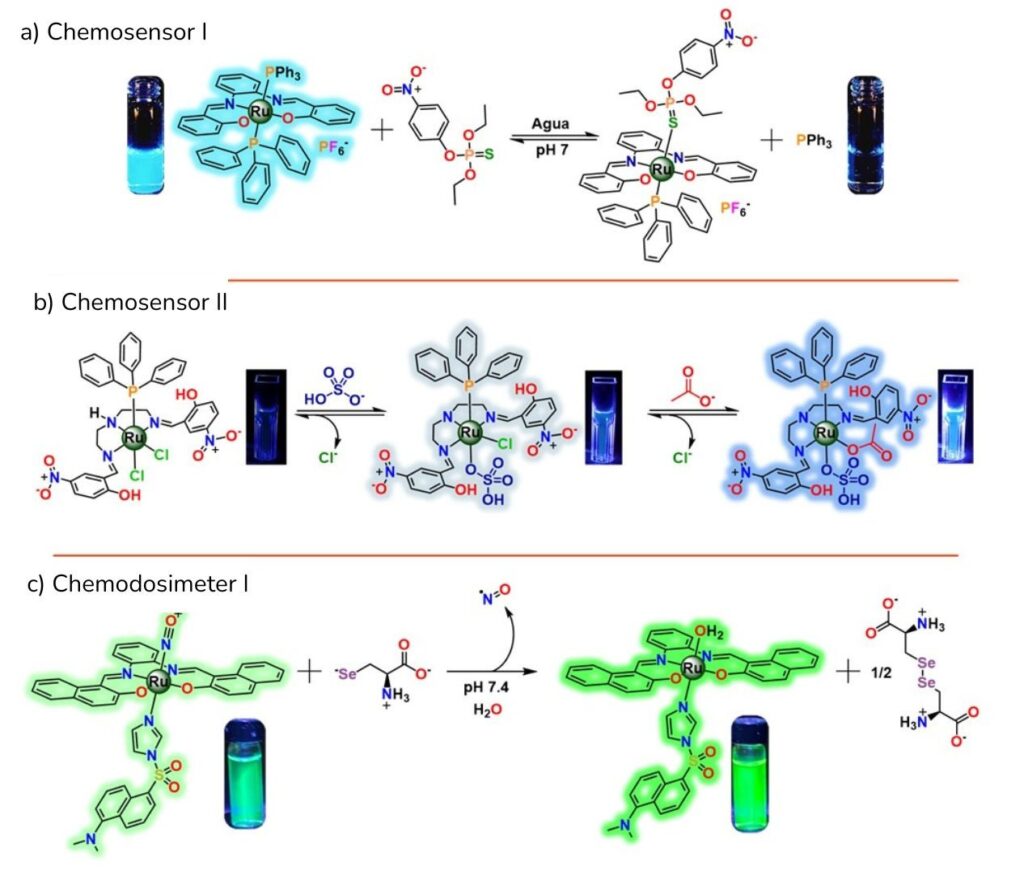

For example, we’ve found that Chemosensor I—a Ru³⁺ compound that dissolves in water at neutral pH—normally emits blue light (photoluminescence). However, when it detects the insecticide parathion, that blue emission almost completely switches off.

Detecting this contaminant is critical because it is extremely toxic to humans, fish, and amphibians—even at very low concentrations. So if there’s reason to suspect that a water sample contains this pesticide, adding the ruthenium sensor will cause it to dim instead of glowing bright blue, signaling the contaminant’s presence.

We’ve also found that Chemosensor II, which contains a Ru²⁺ ion and emits blue light, can detect bisulfate and acetate—ions whose presence and concentration are important in biochemical and industrial processes. This detection occurs through a photoluminescent Off–On mechanism, meaning the sensor’s light intensity increases when it encounters these substances.

Finally, we have also found that Chemodosimeter I can detect selenocysteine, an amino acid linked to diseases such as cancer and diabetes, making its monitoring useful for diagnosing metabolic disorders.

This sensor, which combines a Ru²⁺ ion with a photoluminescent dye that emits green light, reacts by producing a brighter green glow when it detects the amino acid.

A) Chemosensor I: An On–Off sensor designed to detect parathion, a highly toxic insecticide.

B) Chemosensor II: An Off–On sensor capable of sequentially detecting bisulfate and acetate—anions relevant to biochemistry, the pharmaceutical industry, and the food industry.

C) Chemodosimeter I: An Off–On sensor used to detect selenocysteine, an important biological marker for diagnosing diseases such as cancer and diabetes.

.

The Future of Molecular Sensors

These molecular detection tools are essential to modern life, making it increasingly important to develop new sensors capable of identifying substances that threaten human health and the environment.

In the years ahead, this technology will also be used to track emerging contaminants in air and water supplies—including residues from new pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and agrochemicals—and even to detect biological markers linked to emerging diseases.

.

Authors

Iván J. Bazany-Rodríguez. Postdoctoral researcher at UNAM’s Faculty of Chemistry and lecturer at UNAM’s Faculty of Sciences. He holds a PhD in Chemical Sciences and specializes in designing and fabricating artificial optical receptors for photoluminescent chemodetection of organic contaminants, toxic ions, and biological markers relevant to diseases such as cancer and diabetes.

Jessica M. Muro-Hidalgo. Chemical Engineer with a Master’s in Environmental Engineering from UNAM. She has developed photoluminescent nanosensors for the chemodetection of toxic metal ions and biogenic amines like histamine, using carbon quantum dots derived from waste materials such as PET. She is currently pursuing a PhD in Environmental Engineering (UNAM), focusing on metal-oxide composite nanomaterials and carbon quantum dots for the detection and adsorption of carbon dioxide.

Axel Macias-García. Environmental Engineer trained at the National Technological Institute of Mexico with a Master’s in Environmental Engineering from UNAM. His work includes electrocoagulation projects for arsenic removal at the Mexican Institute of Water Technology, phenol removal through Fenton processes at CIDETEQ, and electrochemical detection of pesticides using nanostructured electrodes at UNAM’s Faculty of Chemistry. He is now pursuing a PhD in Environmental Engineering, focused on developing nanomaterials for the electrochemical detection of environmentally and medically relevant molecules.

J. Guadalupe Hernández-Hernández. Academic technician and lecturer at UNAM’s Aragón School of Higher Studies. He holds a PhD in Chemical Engineering, with research lines in inorganic chemistry, computational chemistry, photocatalysis, and electrochemistry.

Carlos Alberto Huerta-Aguilar. Professor at Tecnológico de Monterrey. He holds a PhD in Environmental Engineering and specializes in solar-driven catalysis, waste valorization, and circular chemistry. He completed postdoctoral work at Stanford and Texas A&M and co-leads international projects on hydrogen, biogas, and agrivoltaics. He has also contributed to TecScience as a science communicator.

Pandiyan Thangarasu. Senior researcher and professor at UNAM’s Faculty of Chemistry. He holds a PhD in Chemistry. His research focuses on coordination chemistry, catalytic systems, and green remediation strategies. He is recognized for his work on metal–organic complexes and advanced oxidation technologies, with collaborations across Latin America and Asia. He is also a contributor of science outreach articles for TecScience.