Por María Teresa Santos, Alejandro García y Yocanxóchitl Perfecto

The microbiota has become an increasingly prominent topic in both the scientific community and public conversation—and for good reason. Inside us lives a vibrant, ever-changing ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, and fungi that work together to perform essential functions. They help digest food, train the immune system, and are key to maintaining bodily homeostasis—that is, the body’s ability to keep its internal balance [1].

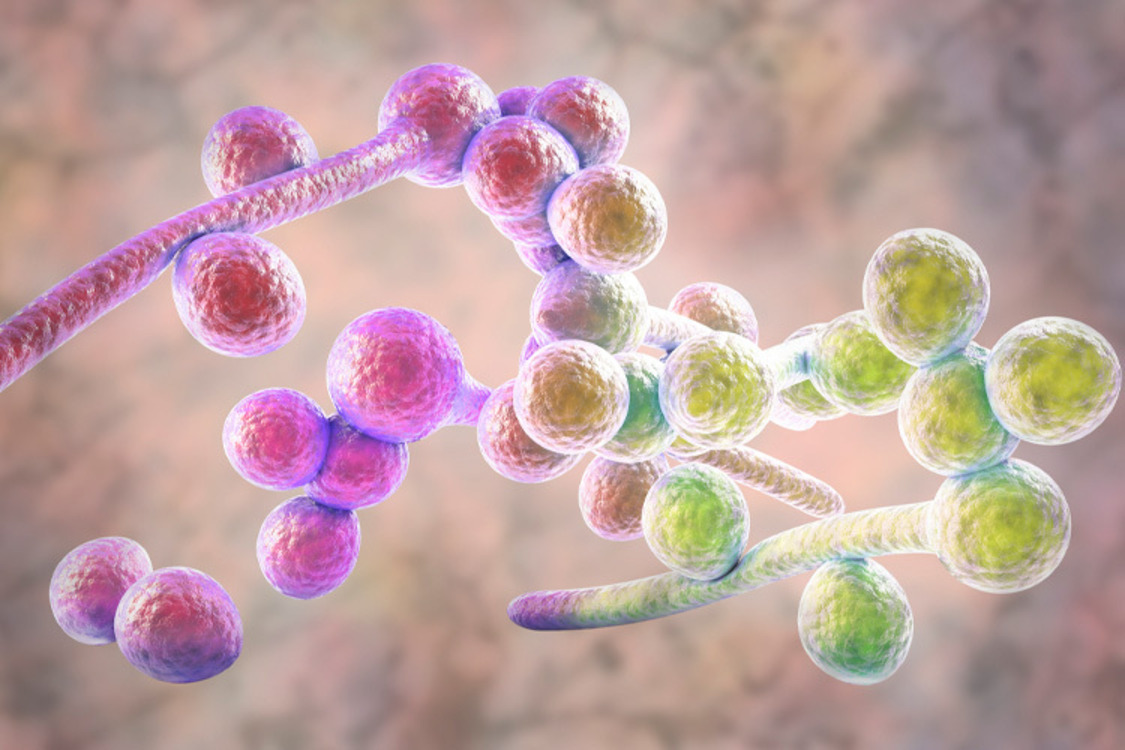

Within this internal ecosystem, Candida albicans is a common and usually discreet resident. This fungus is found in the mouth, the gut, and other mucosal surfaces, where under normal conditions it lives quietly and in harmony with its microbial neighbors [2].

That peaceful coexistence, however, is fragile. External signals can disrupt C. albicans’ harmless behavior, turning it from a “good neighbor” into a troublesome opportunist [3].

Candida albicans: A shift in perspective

For a long time, Candida albicans was viewed strictly as a pathogen—a direct cause of infection and disease. Today, we know that the view is incomplete. This fungus is part of the microbiome in most people and often coexists without causing harm, and may even provide benefits [4,5].

Its asymptomatic, peaceful colonization is still not fully understood. Grasping this dual nature is crucial, as it could significantly reshape our understanding of health.

Identifying the factors that keep this “neighbor” in check—or that trigger its transformation into an “enemy”—is key to developing strategies that promote peaceful coexistence, rather than prioritizing its eradication [6].

Gut bacteria, which play a central role in digestion, directly influence the behavior of Candida albicans.

The key lies in direct or indirect interactions that determine whether the fungus remains a peaceful resident or becomes an invasive threat [7].

This control operates through several mechanisms:

- Direct and territorial competition: Because bacteria are far more abundant, they limit C. albicans growth by competing for nutrients and space along the mucosal surfaces [4,7].

- Immune response: Bacteria help train the immune system to recognize and respond to hostile behavior from C. albicans. In effect, the bacterial community alerts the body’s defenses to contain the fungus when it begins to act out of line [7].

- Production of compounds: Bacteria produce compounds known as postbiotics, such as short-chain fatty acids. These metabolites can inhibit the fungus’s pathogenic—or “enemy”—behavior by blocking its ability to shift into its invasive form [8,9].

.

Bacterial control over Candida albicans is neither uniform nor permanent. Its effectiveness depends on the composition of each person’s bacterial community, as well as external factors such as diet, overall health, and lifestyle habits [10].

When a peaceful neighbor turns invasive

The balance between bacteria and Candida albicans is delicate. When bacterial control fails, the fungus can become invasive. This breakdown of the microbial community is known as dysbiosis, and it signals to Candida that the border is no longer protected [11].

Dysbiosis does not happen by chance. It results from multiple factors that weaken microbial defenses and trigger a shift in the fungus’s behavior.

Prolonged antibiotic use, diets high in sugars and fats, chronic stress, excessive alcohol consumption, lack of exercise, and poor sleep all contribute to dysbiosis. Together, these factors reduce microbial surveillance and damage the intestinal barrier, allowing the fungus to activate its pathogenic form and prepare for invasion [10].

When dysbiosis gives C. albicans the green light, the most common outcome is candidiasis, a superficial infection that includes oral thrush, vaginal yeast infections, and skin infections. In some cases—particularly among immunocompromised patients—the infection can progress to systemic candidiasis, a potentially life-threatening condition [4].

Microorganisms: a constant negotiation

The relationship between bacteria and Candida albicans is not a simple battle, but a constant dynamic negotiation. Maintaining a balanced microbiota—and continually reinforcing that negotiating capacity—is key to preventing infections.

Despite recent advances, science is only beginning to unravel the vast ecosystem that is our microbiota. This rapidly expanding field still faces many unanswered questions due to the complexity of microbial interactions.

Understanding this intricate microbial network is a major step toward a future in which prevention becomes the primary strategy. By viewing bacteria and fungi as interconnected parts of the same system, we shift the focus toward strengthening the entire community rather than simply eliminating a single problem.

Much remains to be discovered, but one thing is clear: health depends on balance and constant negotiation. Recognizing that we are living ecosystems reminds us that maintaining a healthy, consistent lifestyle truly matters. Our health, in many ways, is in our own hands.

.

References

- Chaudhary, P. R. (2024). The Role of Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease: Implications for Therapeutic Interventions. Universal Research Reports, 11(3), Article 3.

- Chow, E. W., Pang, L. M., & Wang, Y. (2024). The impact of the host microbiota on Candida albicans infection. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 80, 102507.

- Li, H., Miao, M., Jia, C., Cao, Y., Yan, T., Jiang, Y., & Yang, F. (2022). Interactions between Candida albicans and the resident microbiota. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13.

- Fróis-Martins, R., Lagler, J., & LeibundGut-Landmann, S. (2024). Candida albicans Virulence Traits in Commensalism and Disease. Current Clinical Microbiology Reports, 11(4), 231–240.

- Schille, T. B., Sprague, J. L., Naglik, J. R., Brunke, S., & Hube, B. (2025). Commensalism and pathogenesis of Candida albicans at the mucosal interface. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 23(8), 525–540.

- Gaziano, R., Sabbatini, S., & Monari, C. (2023). The Interplay between Candida albicans, Vaginal Mucosa, Host Immunity and Resident Microbiota in Health and Disease: An Overview and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms, 11(5), 1211.

- Wang, F., Wang, Z., & Tang, J. (2023). The interactions of Candida albicans with gut bacteria: A new strategy to prevent and treat invasive intestinal candidiasis. Gut Pathogens, 15(1), 30.

- García-Gamboa, R., Perfecto-Avalos, Y., Gonzalez-Garcia, J., Alvarez-Calderon, M. J., Gutierrez-Vilchis, A., & García-Gonzalez, A. (2024). In vitro analysis of postbiotic antimicrobial activity against Candida Species in a minimal synthetic model simulating the gut mycobiota in obesity. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 16760.

- McCrory, C., Verma, J., Tucey, T. M., Turner, R., Weerasinghe, H., Beilharz, T. H., & Traven, A. (2023). The short-chain fatty acid crotonate reduces invasive growth and immune escape of Candida albicans by regulating hyphal gene expression. mBio, 14(6), e02605-23.

- Jawhara, S. (2023). Healthy Diet and Lifestyle Improve the Gut Microbiota and Help Combat Fungal Infection. Microorganisms, 11(6), 1556.

- Dahiya, D., & Nigam, P. S. (2023). Antibiotic-Therapy-Induced Gut Dysbiosis Affecting Gut Microbiota—Brain Axis and Cognition: Restoration by Intake of Probiotics and Synbiotics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(4), 3074.

- Rana, A., Gupta, N., Asif, S., & Thakur, A. (2024). Surviving the Storm: How Candida Species Master Adaptation for Pathogenesis. In S. Hameed & P. Vijayaraghavan (Eds.), Recent Advances in Human Fungal Diseases: Progress and Prospects (pp. 109–155). Springer Nature.

- Peroumal, D., Sahu, S. R., Kumari, P., Utkalaja, B. G., & Acharya, N. (2022). Commensal Fungus Candida albicans Maintains a Long-Term Mutualistic Relationship with the Host to Modulate Gut Microbiota and Metabolism. Microbiology Spectrum, 10(5), e02462-22.

.

Authors

María Teresa Santos Ramírez holds a degree in Biotechnology Engineering and is a master’s student in Biotechnology at Tecnológico de Monterrey, with a research stay at the Kalundborg eco-industrial park in Denmark.

Alejandro García González holds a PhD in Science with a specialization in Automatic Control. He is a research professor at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences at Tecnológico de Monterrey and a member of Mexico’s National System of Researchers. He is also the co-founder of two startups.

Yocanxóchitl Perfecto Avalos holds a PhD in Engineering Sciences. She is Associate Director of the Regional Department of Bioengineering and a research professor at the School of Engineering and Sciences at Tecnológico de Monterrey. She is a member of the National System of Researchers and a science communicator and contributor to TecScience.