By Ryan Anders Whitney and Luisa Sotomayor

In many Latin American cities, city governments often borrow urban planning “best practices” from other places – projects, policies, or strategies that have worked well elsewhere- and attempt to adopt them locally.

Historically, many best practices have focused on the central areas of cities ripe for tourism and investment, such as pedestrian streets or historic center revitalization.

More recently, however, best practices have shifted to the edge of the city.

These areas may not only be physically distant from city centers but also socially and economically marginalized, having been built over decades by residents themselves, often without state support. While many now have paved roads, running water, and public schools, they still face big gaps in public services and economic opportunities.

In these neighborhoods, “peripheral best practices” are sometimes designed to be visually impressive more than practically useful. Politicians may focus on projects that look good on camera and make for good headlines, even if they don’t impact the local quality of life. This reflects what we call “the politics of visibility”: when politicians prioritize a project’s image and media appeal over its long-term value.

Social Urbanism in the Peripheries

In 2019, in Mexico City’s Álvaro Obregón borough, the mayor announced a project inspired by Medellín’s “social urbanism”, an urban model that began in the early 2000s involving investments in public space, education, transport, safety, and community development, especially in poor neighborhoods.

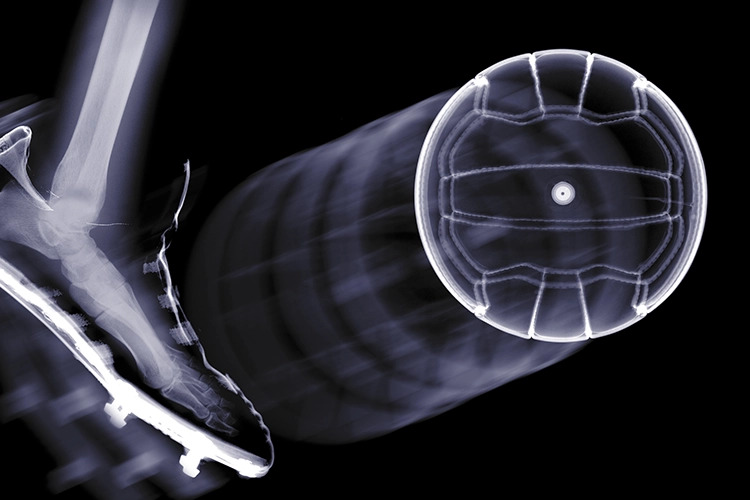

One of Medellín’s most iconic projects was a set of outdoor escalators in Comuna 13. These helped residents navigate steep terrain and became a global symbol of inclusive urban transformation.

Seeking to replicate this success, the Álvaro Obregón mayor launched the “Escalators of Justice.” The plan included three escalator segments (260 meters total) and other public improvements. It was framed as bringing “social justice” to one of Mexico City’s marginalized areas.

But by 2020, only one 50-meter escalator had been built. The rest of the project was scrapped. The escalator only ran uphill in the morning and downhill in the evening, and it did not connect to key destinations. As a result, very few people used it.

In 2021, a new mayor from a rival party shut it down, calling it a waste of money. The media dubbed it the “Escalators of Injustice.”

What Happened? The research “Peripheral best practices and the politics of visibility: Urban planning and social urbanism in Mexico City” highlights several reasons why the project failed, while challenging reliance on best practices.

Political Spectacle vs. Solution

One major factor was short political timelines. With three-year mayoral terms, local governments often rush to complete visible projects instead of investing in long-term planning. This led to a simplified, scaled-back version of the original plan.

There was also a lack of genuine community input. Unlike Medellín, residents in Mexico City were consulted after key decisions had been made. Many locals did not want an escalator; they preferred other, less flashy investments.

The design itself was flawed. The escalator was placed in an area with little foot traffic and felt unsafe due to high tunnel-like walls. It did not match people’s daily routes and was inconvenient because it ran only one way at a time.

Finally, the project lacked expertise in urban planning. It was not part of a larger mobility plan and failed to address gender-specific needs, such as the safety and mobility of women, who are key users of pedestrian infrastructure in the area.

This particular case in Mexico City reflects a growing trend in Latin America: cities increasingly look to other Latin American cities for urban planning inspiration, thereby challenging dominant best practices from the Global North. These Latin American exchanges can feel more relevant to local realities.

However, even well-regarded best practices can fail when transplanted without attention to local context. Medellín’s experience, while imperfect, was built on sustained investments, cross-agency coordination, and meaningful community participation.

That does not mean peripheral best practices are inherently flawed. In Mexico City, other projects like cable cars and the “utopías” community centers in Iztapalapa, also partially inspired by social urbanism, have shown potential to meet community needs while also gaining political visibility.

But for peripheral best practices to succeed long-term, they must be more than symbolic. They need to be part of long-term plans, not only tied to short-term political cycles. They must involve communities from the beginning, be guided by urban planning experts, and connect residents to real opportunities and destinations.

Without these elements, peripheral best practices risk becoming empty spectacles shaped by the politics of visibility – projects that sound promising in theory but fail to deliver real, lasting change.

.

References

- Sotomayor, L. (2015). Equitable planning through territories of exception: The contours of Medellin’s urban development projects. International Development Planning Review, 37(4), 373–397.

- Whitney, R. A., & Sotomayor, L. (2025). Peripheral best practices and the politics of visibility: Urban planning and social urbanism in Mexico City. Cities, 158, 105667.

.

Authors

Ryan Anders Whitney. Assistant Professor (Research) in the School of Architecture, Art and Design at the Tecnológico de Monterrey (Mexico City Campus). His research focuses on urban policy and planning equity, exploring the local and global dynamics that influence the movement and adoption of policy models.

Luisa Sotomayor. Associate Professor and the Director of the Program in Planning in the Department of Geography and Planning at the University of Toronto. Her research and teaching interests focus on the dimensions of urban inequality and their connections to governance and urban planning practices.